Illustration of the affective and visceral

Author:

Verena Schröder

Citation:

Schröder, V. (2024): Comics. Illustration of the affective and visceral. In: VisQual Methodbox,

URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2023/10/17/comics/

Essentials

- Systematization: In geography, three different approaches to comics can be identified: (1) comic analysis, (2) comic semiotics and (3) comic practice (Schröder 2022).

- Aims: In their comic drawings, geographers try to make specific viewpoints, moments, emotions and relations visible that have been underexposed either socio-politically or in terms of scientific practice.

- Advantages: Comics are well-suited for expressing nonverbal, affective and visceral aspects.

Description

Comics offer the opportunity to depict movement processes, gestures and facial expressions, emotions and moods, corporeal aspects, and affects. In doing so, relations between entities become visible, which is why they have played an important role in narrating human-animal relationships (e.g. Lucky Luke, The Peanuts with Snoopy and Charlie Brown, Garfield, etc. – for a review see Herman, 2018). More than other forms of scientific expression, comics have the ability to show intimate connections between humans and non-humans (see Calvin and Hobbes by Watterson 2003) or to blur the boundary between living beings (see the famous comic strip Maus by Spiegelman 1986). In this context and due to the simultaneity of material, corporeal, discursive, performative and visceral processes, comics are more easily and quickly accessible to people than text.

Comics have recently gained attention as a research and communication medium across a range of academic disciplines (Kuttner et al. 2020). Both natural and social sciences are being explored through comics. Peer-reviewed journals such as The Comic Grid, Journal of Comics and Culture, Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, and Sequentials have been established to support the production and dissemination of knowledge through comic-based content. In geography, comics have received attention under the keywords “Comic Book Geographies” (Dittmer, 2014), “Comic Geographies” (Fall, 2020), and “geoGraphic novel” (Peterle, 2021). Schröder (2022) identifies three different ways in which geographers approach comics: “Comic analysis”, which means that comics are used as data material and are examined in terms of geopolitics (Dodds, 1996; Dittmer, 2007a; Rech, 2014), feminist geopolitics (Fall, 2014), or identity formation (Dittmer, 2007b). In this phase, the medium serves primarily as a basis for content analysis and is seen as a representation of specific socio-political developments and discourses. “Comic semiotics,” as a second phase, focuses primarily on issues related to the construction and reading of image-based narratives, and “comic practice” means that the medium is not only analyzed but also created by geographers themselves or in collaboration with illustrators. These comics are used either as an supplement to scientific texts or without textual explanation.

While comics are an effective way to provide a quick introduction to a research topic, they are also a very challenging form of communication. Not every researcher has the ability to draw or is willing to acquire such skills, and when comics are produced in collaboration with illustrators, they often require financial resources. Furthermore, visual storytelling is open to a wide range of interpretations, so the reader’s perception of a particular comic may differ from the researcher’s original intension.

Procedure

The creation of the comic can be done by the scientist or in collaboration with an illustrator. Depending on the method of creation, the order of the steps may vary. This means that the following steps can be done either together or separately.

- Step 1: The first step is to review the empirical material and consider what story or themes you want to convey. In the case of collaborative comic creation, selected interview transcripts and photos of the research area and interviewees may be provided to the illustrator to help them gain a better understanding of the research topic.

- Step 2: Make initial sketches to familiarize yourself with the visual interpretation of the empirical material.

- Step 3: Develop a script as a basis for the storyboard, including the selection of protagonists and supporting characters.

- Step 4: Creation of the comic (if collaborative, regular consultation with the researcher and review by the researcher).

- Optional: Validating the comic with the people you have interviewed.

Example

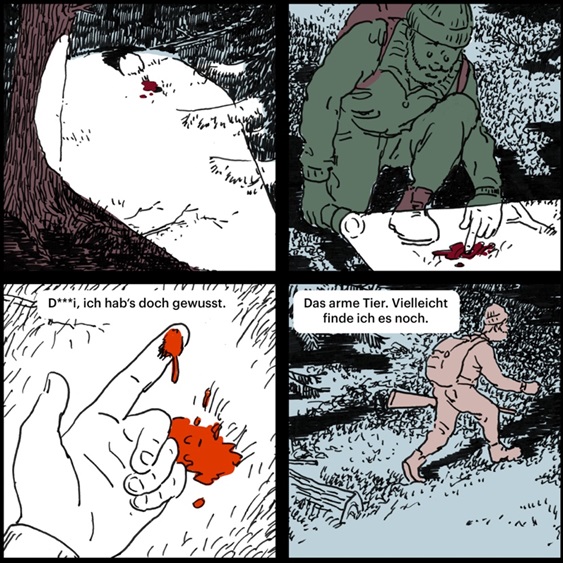

In: Schröder (2022); © Patrick Bonato

This image shows a section of a science comic that aimed to visually convey the corporeal and visceral relationships between humans and wolves, as well as other wild animals. It also critically examined the less discussed issue of accidental shooting by hunters.

Suggested Tools

- Paper & Pencil

References

Dittmer, J. (2007a): The tyranny of the serial: popular geopolitics, the nation, and comic book discourse, Antipode, 39, 247-268. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2007.00520.x

Dittmer, J. (2007b): America is safe while its boys and girls believe in its creeds: Captain America and American identity prior to World War 2, Environ. Plan. D, 25, 401-423. https://doi.org/10.1068/d1905

Dittmer, J. (2014): Comic book geographies, Franz Steiner Verl., Stuttgart. https://www.steiner-verlag.de/en/Comic-Book-Geographies/9783515102698

Dodds, K. (1996): The 1982 Falklands War and a critical geopolitical eye: Steve Bell and the if . . . cartoons, Polit. Geogr., 15, 571-592. https://doi.org/10.1016/0962-6298(96)00002-9

Fall, J. J. (2014): Put your body on the line: autobiographical comics, empathy and plurivocality, in: Comic book geographies, edited by: Dittmer, J., Franz Steiner Verl., Stuttgart, 91-108. https://www.steiner-verlag.de/en/Comic-Book-Geographies/9783515102698

Fall, J. J. (2020): Fenced in, Environ. Plan. C, 38, 771-794. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654420933900

Herman, D. (2018): Animal comics: Multispecies storyworlds in graphic narratives, Bloomsbury, London. https://www.bloomsbury.com/uk/animal-comics-9781350015326/

Kuttner, P. J.,Weaver-Hightower, M. B., and Sousanis, N. (2020): Comicsbased research: the affordances of comics for research across disciplines, Qual. Res., 21, 195-214. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794120918845

Peterle, G. (2021): Comics as research practice. Drawing narrative geographies beyond the frame, Routledge, London. https://www.routledge.com/Comics-as-a-Research-Practice-Drawing-Narrative-Geographies-Beyond-the/Peterle/p/book/9780367524661

Rech, M. F. (2014): Be part of the story: a popular geopolitics of war comics aesthetics and Royal Air Force recruitment, Polit. Geogr., 39, 36-47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2013.07.002

Schröder, V. (2022): More than words: Comics als narratives Medium für Mehr-als-menschliche Geographien, Geogr. Helvetica, 77, 271-287. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-77-271-2022

Spiegelman, A. (1986): Maus: A survivor’s tale, I: My father bleeds history, Pantheon, NY. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maus

Watterson, B. (2003): Calvin and Hobbes (Calvin and Hobbes Collection 1985–86), Andrews a. McMeel, Kansas City, NY. https://publishing.andrewsmcmeel.com/book/calvin-and-hobbes/

Leave a Reply