Author:

Stephan Maximilian Pietsch

Citation:

Pietsch, S. M. (2024): Digital Location-Based Games For Education. In: VisQual Methodbox, URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2023/11/08/digital-location-based-games-for-education/

Essentials

- Classification: Digital location-based games can be classified in the field of digital game-based learning as location-based serious games.

- Advantages: Digital location-based games enable participants to playfully explore out-of-school learning locations by learning with all their senses.

- Education: Digital location-based games should encourage participants – in addition to being motivated by elements such as story, characters, and feedback system – to deal with (educational) content in greater depth.

Description

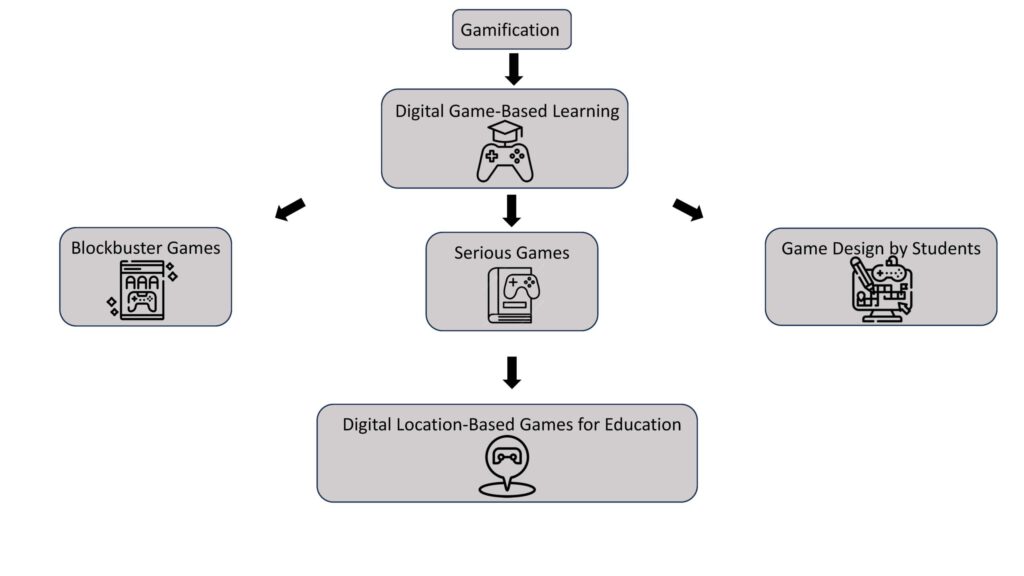

The approach of imparting knowledge in a playful way outside the traditional classroom, as explored here, considers Digital Location-based Games for Education (DLBGfEd) as a unique, interactive form of visual expression, epitomizing a specific genre within digital gaming. Following an image-related definition of digital games as video games, their power result from linking interactive with visual elements. The visual imagery presented on a user’s device is generated anew with each interaction, thus blurring the lines between performativity and representation (see Hensel 2010: 143). Moreover, video games can be seen as a “container” for diverse media types, facilitating the incorporation of text (such as character monologues), visuals (including pictures, maps, infographics), and audiovisuals (like in-game videos). By harnessing these modalities for conveying information, video games have the potential to be integrated into formal educational frameworks under the right conditions. These developments, which are subsumed under the term gamification, among others, will be examined in more detail below to finally locate DLBGfEd in the field of game-based media of knowledge transfer (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Locating Digital Location-Based Games for Education (Design and Realization: S. Pietsch)

As inherently social creatures, humans have historically engaged in games as a learning tool. The Dutch cultural scientist Johan Huizinga refers to this aspect as Homo Ludens (Sailer 2017: 1), illustrating that games have been integral to primary socialization in childhood, significantly influencing the development of personality traits and social skills (Bottino 2019: 1, Van Eck 2006: 18). In educational contexts, it’s crucial to distinguish between “play,” which denotes unstructured activity, and “game,” which implies structured, rule-based engagement. Play is typically characterized by its self-contained nature and the element of choice, whereas games, with their rule-bound and goal-oriented design, align well with formal education structures, such as school curricula (Feulner 2021: 129f.). The focus here is less on the medium itself and more on the content it conveys and the activities it prompts among players (Van Eck 2006: 18). Additionally, it’s important to note another link between games and learning: “The player must have and develop certain skills, both motor and cognitive, in order to engage in gameplay” (Ermy & Mäyrä 2011: 93).

Initial ideas of harnessing the interplay between learning and gaming in education are rooted in behaviourist tradition. As early as the 1920s, and more so in the 1950s and ’60s, there were attempts to use so-called teaching machines to encourage desired behaviors in educational settings through selectively automated rewards (Barth & Ganguin 2018: 530). The term gamification emerged in 2002, but it wasn’t until eight years later that it gained notable traction in academic and educational circles (Sailer 2017: 5). This approach primarily targeted motivational aspects, aiming to provide “spieltypische” (gamelike) experiences to assist individuals in performing monotonous or creatively demanding tasks (Bröker et al. 2021: 504). Thus, gamification can be defined as „die intentionale Übertragung von Computerspielelementen und -mechanismen auf Anwendungen mit spielfremdem Inhalt, immer mit dem Ziel, die Handlungen des Anwenders in bestimmter Weise zu beeinflussen“ (Barth & Ganguin 2018: 533). It is essential to clarify that this process does not involve wholesale game mechanisms but rather selectively employs specific game-related components such as milestones, avatars, and quests (Behl et al. 2022: 1, Bröker et al.2021: 504). Commonly, points, badges, and leaderboards are used, collectively known as the PBL-triad, to engage and motivate users (Tolks & Sailer 2021: 516).

In general, gamification is employed across various sectors, serving as an innovative educational tool. For instance, in Germany, prospective drivers can utilize the app Fahren Lernen Max (Tecvia2023) as a preparatory tool for their theoretical driving exams. The app enhances learning with simulation videos of traffic scenarios and integrates a progress bar to visually track learners’ advancement. Correctly answering questions aligned with the current examination syllabus prompts a traffic light within the app to shift from yellow to green, signaling the user’s readiness for the test. This indication of preparedness is, in some driving schools, a criterion for commencing practical driving lessons. In contrast to this simple gamification example, the language learning app duolingo adopts a more sophisticated set of game mechanics. It features a variety of Non-Player Characters (NPC), a competitive league system based on experience points for user comparison, and an in-app currency (referred to as gems) designed to sustain user engagement and motivation (duolingo 2023).

Based on the definition of gamification as the “Einsatz von spieltypischen Elementen in spielfremden Kontexten” (the utilization of game-like elements in non-gaming contexts) (Bröker et al. 2021: 504), Digital Game-based Learning (DGBL) has emerged as a specialized application within educational settings. It is distinguished by a critical factor: while gamification incorporates game-like elements to boost motivation in non-gaming educational scenarios, DGBL involves the deployment of particular games—known as serious games, educational games, or learning games—with the aim of achieving predetermined learning outcomes (Sanchez 2019: 1). Coined by Marc Prensky in 2001, DGBL pertains to “games designed for, or utilized within, educational contexts” (Breien & Wasson 2020: 91), and explicitly differentiates from traditional formats like role-playing or board games by focusing on digital games (Feulner 2021: 132). Nonetheless, it is crucial to recognize that in these scenarios, gaming serves not merely for entertainment but to accomplish explicit goals and exert tangible change in reality (Barth & Ganguin 2018: 533).

DGBL employs activities that inspire voluntary engagement rather than compulsory participation, aiming to enhance individual motivation towards specific educational content. There’s a general agreement among scholars that DGBL can significantly enhance learning by leveraging narratives to motivate and captivate learners under certain conditions (Breien & Wasson 2020: 92 f.). This shift towards an educational approach that facilitates rather than dictates learning aligns with the belief that learning is most effective when it resonates with personal reasons for action (Bröker et al. 2021: 499). Moreover, the interactive essence of digital games aligns with constructivist theories of learning, which consider learning as an active endeavor. Instead of passively receiving information, students interact with content, often discovering or contextualizing information through exploration (Bereitschaft 2021: 2). Games, particularly digital ones, can foster creativity, enhance logical thinking, and through emotional engagement, help in retaining content for more extended periods (Feulner 2021: 135). In this vein, Richard van Eck references empirical evidence, suggesting that a well-crafted game can improve learning outcomes by up to 40 percent over traditional lectures, potentially equalizing the performance gap between failing students and those achieving a “B” grade (Van Eck 2015: 16).

Beyond “merely” imparting factual knowledge, methods of DGBL are particularly effective for competence development. They emphasize the process of exploring various problem-solving strategies and engaging in playful decision-making. This approach can challenge and expand students’ understanding of the world, offering a reflective space to reassess conceptual knowledge (Bereitschaft 2021: 3). Video games often present players with a problem or quest that requires learning and applying game mechanics, thus fostering problem-based learning (Van Eck 2015: 16). Video games are especially valuable in the context of Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) – in German referred to as Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung (BNE) – and civic education, where they allow for the exploration of different courses of action and the virtual simulation of multiple perspectives on issues (Czauderna & Budke 2021: 96). Moreover, as digital services increasingly permeate daily life, digital games can be used to enhance essential media competencies—from operating devices to evaluating information credibility. DGBL can thus be woven into formal education in several ways. Notably, research literature frequently spotlights three approaches: Commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) blockbuster games, student game design, and serious games, each of which will be discussed in more detail (Van Eck 2006: 20, Van Eck 2015: 18).

Commercial games, particularly the widely recognized AAA or blockbuster titles, are a commonly utilized and cost-effective approach for integrating gaming into educational settings (Van Eck 2015: 20; Van Eck 2006: 22). It is often posited that these games may surpass classical educational games in motivating learners within certain pedagogical contexts, suggesting their preference under specific conditions in both formal and non-formal education (Czauderna & Budke 2021:95). The appeal of blockbuster games in education is also supported by their popularity among students. For instance, in the JIM Jugendstudie, a mere six percent of respondents reported never playing games, while 76 percent regularly engage with video games (Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest 2022: 49). This highlights their potential as a bridge to student interests. Additionally, these games are noted for their high-quality, market-tested, consumer-friendly attributes. Bradley Bereitschaft acknowledges the value of incorporating commercial city-building games into teaching, stating that as simulations of complex, real-time evolving systems presenting players with dynamic challenges, they could significantly aid in the development of critical thinking, problem-solving, and systems-thinking skills (Bereitschaft 2021: 2). However, despite these potential benefits, it’s crucial to conduct a thorough analysis of their educational appropriateness, as commercial games are primarily designed for entertainment and profit, not educational purposes (Van Eck 2006: 22).

Overall, “Learning by doing” is a key principle of DGBL and is equally significant in the second category of educational use of video games, where learners participate in game development. This hands-on approach to game design ensures that learners deeply engage with the educational content, as they learn through the act of creating the game (Van Eck 2006: 20). Beca et al. (2020) outline several benefits from this method: students gain greater interest in the subject matter, appreciate the value of their learning, grasp scientific concepts, and enhance their technological and digital literacy. Furthermore, it fosters an interest in programming and design, encourages responsibility and positive group work attitudes, and boosts students’ sense of achievement, self-confidence, and self-efficacy, making them more invested in the coding and implementation process (Beca et al. 2020: 98f.). However, this approach is time-intensive and may not fit the time constraints of formal education structures, such as the limited hours allocated for subjects like geography in middle and high schools. Additionally, it raises the issue of the necessary qualifications for teaching staff, as not all educators are equipped with game design skills (Van Eck 2006: 20).

The development of serious games, which are designed for the engaging delivery of specific content and competencies, stands as the costliest but also the most promising method (Van Eck 2015: 18). Gaining acceptance for these games from their intended audience is often a resource-intensive process. As Van Eck notes, “because the games must be comparable in quality and functionality to commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) games, which are very effective in teaching the content, skills, and problem-solving needed to win the game” (Van Eck 2006: 20). Serious games face several development challenges; they are not solely educational but are hybrids that incorporate aspects of e-learning, game mechanics, and storytelling, all while prioritizing an enjoyable experience (Robinson et al. 2021: 2). The design of serious games aims to facilitate learning of higher-order thinking skills and to create gameplay that extends beyond rote activities (Charsky 2010: 180). The format of DLBGfEd, as discussed here, is a specialized category of location-based serious games intended for learning at extracurricular sites or in outdoor education. This approach to in situ learning was advanced by an interdisciplinary team through a BMBF-funded project (Head of the Project: U. Wardenga) from 2018 to 2022, involving the Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde in Leipzig as the lead and the Naturpark Barnim in Wandlitz as a practical partner (Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde 2023).

Digital Location-Based Games (DLBG) or geo-games, as described by Feulner (2021: 147), are initially defined as any game “that incorporates the players‘ physical location and/or actions in an outdoor or public space into the game via a networked interface” (Leorke 2019: 38). Drawing an analogy to geocaching infused with game elements, the progression of the game is closely tied to locating specific coordinates, which might, for instance, unlock the next segment of the game’s narrative (Pietsch 2022: 278). The direct association with the location emerges as the central aspect of the gaming experience (Feulner 2021: 148). Because of their mechanics, DLBG are aptly suited to transition educational approaches from indoor settings to the outdoors. They align with ongoing subject-didactic constructivist discussions, enabling learners to explore a location through digital devices, such as smartphones or tablets. This allows for an autonomous and multisensory experience (Lämmchen & Pietsch 2023: 289), blending the tangible world with the virtual realm (Pietsch 2022: 278). In the context of such gameplay, the players move in physical space, as certain locations are visited, artifacts are inspected and the results are saved, e.g., by taking photos or recording audio. At the same time, they act in virtual space, for example by solving puzzles, interacting with virtual characters and generating or assigning digital information’ (Stintzing & Pietsch 2021: 356). This augmented reality technique is notably promising, because it encourages participants to explore their surroundings, produce content, navigate real environments, collaborate, and collectively address challenges (Feulner 2021: 147). Moreover, it aligns with several competencies outlined in educational curriculums, not limited to geography alone. Additionally, a distinctive DLBG design can provide varied perspectives on topics related to a particular learning site, aiding in the development of dialogic skills. In line with the educational principle one location – one topic (Hemmer 1996: 15), each game station can represent a distinct viewpoint, possibly showcased by an NPC, on a learning site. One of the primary objectives is to induce moments of dissonance among players, urging them to critically reevaluate broader contexts. This juxtaposition of real-world experiences and digital realities presents an intriguing dynamic for the nexus between video games and transformative geographic education.

In summary, the concepts of gamification and digital game-based learning have garnered significant attention recently, predominantly within educational spheres. According to the Gartner Hype Cycle for Education, gamification has already passed the first three stages of the hype process and is in the consolidation and implementation phase” (Tolks & Sailer 2021: 528). Geographical education is no exception, with pivotal conceptual contributions to digital excursion didactics (refer to Hiller et al. 2019) and digital location-based games (see Feulner 2021, Leorke 2019). Practically, place related augmented reality (AR) solutions are predominantly employed in museal education and from institutions, which focus on regional outdoor education (for example nature parks), where this often can be seen as an evolution of traditional methodologies, like audio guides. Collaborative endeavors frequently occur with private-sector entities, resulting in bespoke solutions (such as those from Locandy) or providing modular systems for game development (like actionbound).

While the numerous benefits and expectations associated with gamified learning, especially DLBG, are often discussed, there are also valid criticisms of the approaches, especially when used in formal educational settings. When considering gamification as a whole, it’s essential to question whether it truly represents a progressive trend that benefits learners in the realm of education, or if it’s simply the latest buzzword targeting consumer motivation and profit generation. Given the existing pressures on students due to performance-driven educational systems, it’s worth pondering if introducing another method with additional rules and evaluation mechanisms is wise. Such methods could exacerbate stress by emphasizing outcomes, like fostering competition through performance rankings.

Beyond these broader concerns related to the implementation of DGBL into the sphere of (formal) education, especially serious games have garnered some skepticism. Much of this arises because they often cloak traditional learning and practice activities under the guise of a “game” rather than offering genuinely engaging gameplay (Charsky 2010: 177). This is evident in their limited interactivity and less compelling visuals (Lux & Budke 2020: 24). As a result, students tend to prefer integrating entertainment-focused games into educational contexts over typical serious games (Czauderna & Budke 2022: 180). As Shen et al. (2009: 48) note, “The seriousness of serious games may already diminish the pleasure even in sophisticated games.” Turning to DLBG, insights from the SpielRäume-project reveal concerns not just about the high costs of game creation, but also challenges related to game execution. For instance, even if mobile devices aren’t supplied by the developers, it’s crucial to ensure game compatibility with various operating systems (Android, IOS) and make adjustments when required. Moreover, uninterrupted access to game coordinates is vital; any obstructions from construction or other barriers can disrupt the game, making regular site inspections a necessity.

While it should be clear that the integration of video games in educational settings is not a one-size-fits-all solution—as stated by Van Eck (2015: 24), “DGBL is no panacea. It will not work and is not practical for all learners, all content, all the time – any more than are lectures and textbooks”—it also raises several media-ethical concerns. Specifically, AAA titles, known for their intricate feedback and reward systems, could encourage media escapism or even lead to addiction. Additionally, before integrating any game into an educational setting, there’s a crucial need for deliberate planning to ensure inclusivity. This is vital, as video games, being powerful multimedia representations, can substantially influence and shape individual perspectives. It’s crucial to note that entertainment-focused games are not value-neutral; they inherently reflect the beliefs and biases of the developers, often subtly integrated into the game’s narrative and mechanics. Bradley Bereitschaft’s study on the educational implications of city-building games emphasizes the need for reflection, pointing out that such games “may communicate an incomplete and ideologically-biased view of urban systems, especially the nature of urban planning, politics, and power” (Bereitschaft 2021: 6). Yet, video games can also champion counter-narratives, serving as intriguing platforms for exploring utopias or challenging prevailing ideologies. A prime example is the 2023 game Terra Nil by Free Lives, a reverse city builder where players work to restore a post-apocalyptic urban wasteland back to its natural state. This concept sharply contrasts with traditional city-building game mechanics.

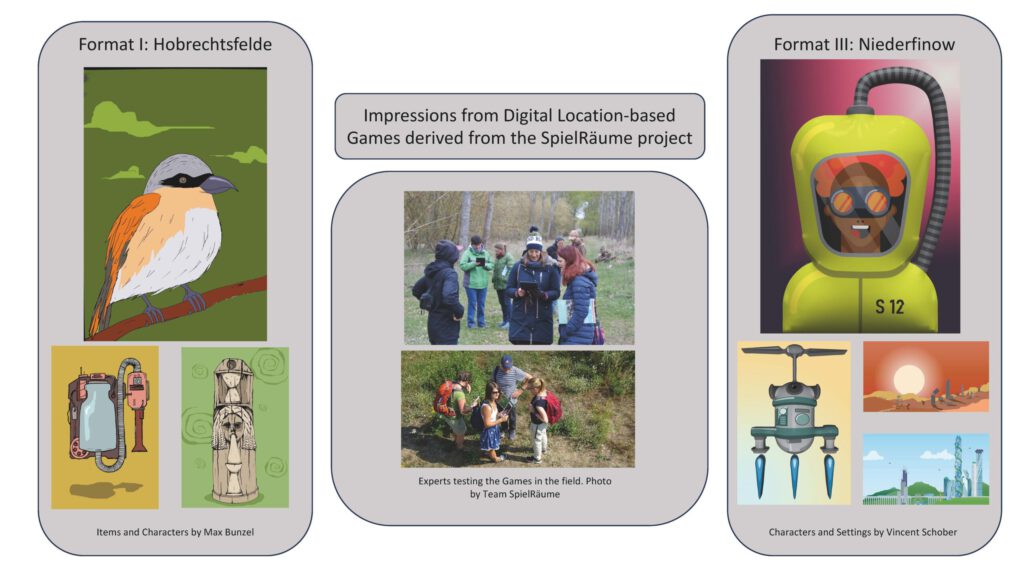

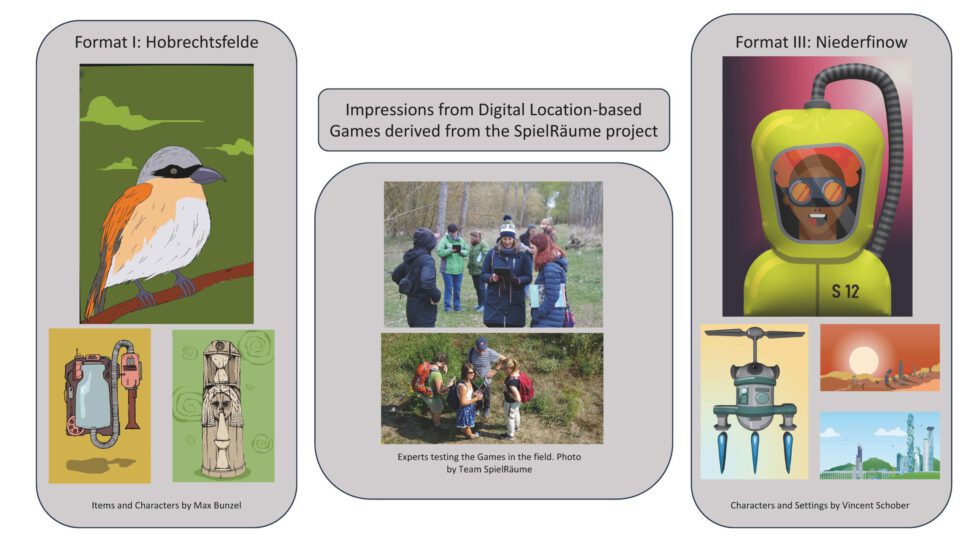

The complexities involved in developing digital location-based games for educational purposes become evident when considering the dual challenge of game and educational design (Czauderna & Guardiola 2019: 207). To sustain engagement, it’s crucial that the educational content is integrated seamlessly, allowing participants to identify more as gamers than as learners (Feulner 2021: 141). The goal is to ensure that the educational thrust isn’t too dominant, necessitating a delicate balance between learning objectives and playful elements (Gryl 2022: 364f.; Feulner 2021: 141). Contemporary approaches lean towards player-centered game design, emphasizing games should be intuitive, enjoyable, emotionally resonant, and consistently motivating—facilitating what’s often termed a “state of flow” (Czauderna & Guardiola 2019: 214). Notably, the visual appeal of the game—including character design, in-game cinematics, items, and more—is crucial both for player enjoyment and for effective content delivery. As Martin & Shen (2014: 36) note, “a high-quality aesthetic presentation can foster a positive bias among users, encouraging deeper and more efficient engagement with the educational content.”

Figure 2: Impressions from Digital location-based Games for Education (Design and Realization: S. Pietsch)

Given the often-limited development budgets for serious games compared to AAA titles, striking a balance becomes challenging. Despite these constraints, educational games are still evaluated against the visual benchmarks set by professional video games. This pushes developers, especially those with tighter budgets, to maximize their creative capacities. Incorporating popular culture references from other media can positively impact the player’s experience. This extends not just to game mechanics, like the inclusion of an inventory, but also to design elements such as non-playable characters (NPCs) and specific items—take the ‘Ghostduster‘ shown in Figure 2 as an example. The sidekick character ‘Drohni,’ introduced to players in a DLBG on climate change at the Niederfinow ship lift (Pietsch 2022: 280), is reminiscent of ‘Claptrap‘ from the renowned Borderlands video game series. Regardless of the references and inspirations, it’s essential to maintain a consistent style across all visual elements—whether they’re in-game videos or character animations—to ensure the game feels cohesive and as if crafted from a single vision. Figure 2 provides a visual compilation of diverse design impressions from the SpielRäume-project.

Procedure and Example

The SpielRäume-project yielded insights into two distinct methodologies for devising game-based digital excursions. When collaborating with an external service provider, much of the technical processes, notably content creation, are sourced out, which can lead to intricate communication channels (Heyer et al. 2022). In contrast, an in-house production approach, assuming the availability of skilled personnel, can be both cost-efficient and allow for greater flexibility.

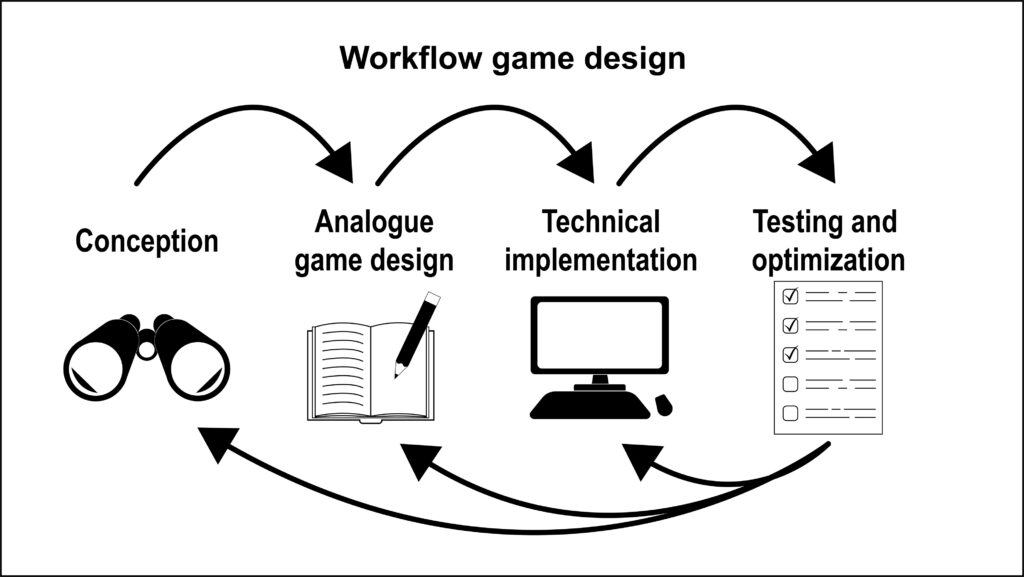

This discussion will now outline the prototypical developmental stages from inception to a twice-verified beta version of a DLBG. This structure stems from the foundational document released by the SpielRäume-project, which delineated the process of crafting digital excursion games (Pietsch et al. 2022). In an ideal scenario, the entire workflow can be categorized into four primary phases, each encompassing various interconnected tasks (refer to Figure 3). Nevertheless, these phases are dynamic, with the potential for foundational re-evaluations throughout, particularly during testing. Such revisions might entail the complete overhaul of character designs or significant alterations to core conceptual components.

Figure 3: Workflow Design Digital Location-based Games for Education (Design: Stephan Pietsch. Realization: Marc Wallenta)

The Conception-Phase kicks off with a detailed survey of the intended game location. This primary assessment facilitates an understanding of the locale’s features and dynamics. Post this exploration, if a clarity emerges about the themes apt for transmission at this educational site, the next task is to specify the game’s target audience. This decision profoundly impacts both the content conveyed and the selection of game mechanisms and elements. Subsequently, the learning objectives are delineated, and an overarching narrative or theme is established. The first phase culminates with a thorough review of literature and various media (like films, images, and so forth) that resonate with the selected themes of the game’s application.

Following the initial conception, the aim of the Analogue game design is to convert the content from the learning site into a coherent game concept, incorporating foundational elements like narrative, characters, quests, and feedback mechanisms (Lämmchen et al. 2022). The preliminary task involves streamlining individual educational stations into a logical route, supplemented by a corresponding overarching story. By this stage, it’s crucial to settle on a suitable software platform, as it demarcates the boundaries and opportunities for the subsequent steps. Once these foundational parameters are established, the narrative can be refined, character designs fleshed out, and preliminary ideas for a feedback mechanism deliberated. These concepts are then field-tested for their gaming potential during a second visit to the site.

After confirming the feasibility, the next step is the technical implementation, where the analogue design is integrated into the chosen software solution. This encompasses several tasks: the visual creation and possible animation of characters, scriptwriting and musical accompaniment for dialogues, and the introduction of feedback mechanisms and quests. A significant portion of time (and budget) is dedicated to producing audiovisual content. For instance, crafting just one minute of film, inclusive of its preparation, demands roughly five hours from a skilled professional.

After incorporating all the materials into the game, a preliminary version emerges. The onset of the crucial final phase begins with its internal testing. This phase is typically marked by iterative testing and enhancement cycles, culminating in a targeted group test. The feedback from this evaluation informs the creation of the beta version.

Designing a DLBG is a comprehensive and resource-intensive endeavor, demanding a convergence of various expertise, especially when the emphasis is on ensuring playability. A foundational grasp of gamification principles and the intended content is essential. Moreover, expertise in media design and pedagogical strategies is crucial to cater to specific audience needs. In educational contexts, such as student projects, creating interactive games can serve as a dynamic, semester-long activity that offers a fresh approach to understanding content and developing skills. However, the standards are significantly higher for the design of professional DLBG meant for broader application. The development process for these games can span between one and two years (Van Eck 2006: 20). From a scholarly standpoint, the creation of these games often involves interdisciplinary collaboration, entailing significant personnel expenses. Moreover, ,,die kooperative Zusammenarbeit (z.B. zwischen Spieleentwicklern, Lehrkräften, Didaktikern) erscheint (…) als zielführendste Lösung, um die Kontextualisierung von Bildungsinhalten und weitere pädagogisch-didaktische Gesichtspunkte mit Spielemechanismen zu verbinden” (Feulner 2021: 155).

Evaluation

The location-related method of playful knowledge transfer was developed in partnership with Naturpark Barnim (Wandlitz) under a project funded by the BMBF at the Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde (Leipzig). To this end, three digital location-based games were designed, executed, tested, and refined to their beta versions (Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde 2023). Teachers who were eager to experiment with fresh, innovative formats – such as those suitable for hiking days – particularly sought these offerings. Additionally, significant interest arose from the realm of geography education and the training of teacher students. Institutions with a focus on excursion didactics, such as TU Dresden (Nicole Raschke), HU Berlin (Karoline Kucharzyk), and MLU Halle-Wittenberg (Eva Nöthen), were notably involved in this domain. Moreover, the broader public is increasingly engaging with digital scavenger hunts in the tourism sector, as evidenced by offerings from the Austrian provider, Locandy (Locandy 2023).

However, an in-depth empirical analysis, potentially within the scope of third-party funded research, is crucial to formalize this method. This becomes especially significant if digital game-based learning outside the classroom is envisioned as a core part of the educational curriculum. The design seems to inherently provide comprehensive learning packages tailored to individual class curriculums. These packages include preliminary and follow-up phases, with the location-based serious games acting as the core implementation phase. Introducing playful learning methodologies during teacher training could be beneficial. This would ensure that educators are familiar with the strengths and pitfalls of the approach before stepping into the classroom. It’s essential to note that the aim of these digital game-based learning tools isn’t to replace traditional educational methods. When used thoughtfully and critically, they can enhance engagement with topics, such as geography, and foster a deeper understanding. They also play a role in competency development. With digital location-based games, when integrated effectively into educational processes, they can amplify awareness and understanding of overarching themes, like climate change or globalization, which might otherwise remain abstract.

Useful Ressources

- Example 1: Stadtentwicklung spielend erleben: spielerische Wissensvermittlung eines Leipziger Stadtentwicklungsprojektes (https://landschaften-in-deutschland.de/themen/78_b_167-parkbogen-ost/)

- Example 2: Geschichte eines Leipziger Landschaftsparks vor Ort spielerisch erleben (https://landschaften-in-deutschland.de/themen/78_b_156-mariannenpark/)

- Online Presentation: Raumbezogene Inhalte spielerisch vermitteln. Ergebnispräsentation des Projektes SpielRäume, von Stephan Pietsch und Robert Lämmchen (https://vimeo.com/522221736)

- Handout: EDU Guide Actionbound zum Erstellen digitaler Schnitzeljagden (https://content.actionbound.com/upload/Actionbound-EDU-GUIDE.pdf)

- Handout: Workflow zur Erstellung digitaler Exkursionsspiele (https://leibniz-ifl.de/fileadmin/download/SpielRäume3_Workflow.pdf)

- Handout: Die Erstellung eines ortsbezogenen Lernspiels mit einem externen Dienstleister (https://leibniz-ifl.de/fileadmin/download/SpielRäume1_eDL_Workflow.pdf)

- Handout: Grundbegriffe digitaler, spielerischer und ortsbezogener Wissensvermittlung (https://leibniz-ifl.de/fileadmin/download/SpielRäume2_Grundbegriffe.pdf)

Suggested Tools

- Actionbound (https://de.actionbound.com)

- Adobe Creative Cloud (https://www.adobe.com/de/creativecloud.html)

- Blender (https://www.blender.org)

- Locandy (externer Dienstleister) (https://multimedia-audioguide.locandy.com)

- Wherigo (https://wherigo.com)

References

Barth, R. and S. Ganguin (2018): Mobile Gamification. In: De Witt, C. and C. Gloerfeld (eds.): Handbuch Mobile Learning. Wiesbaden: Springer, 529-542. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-19123-8_26

Beca, P., Aresta, M., Ortet, C., Santos, R., Veloso A. I. and S. Ribeiro (2020): Promoting student engagement in the design of digital games. The creation of games using a Toolkit to Game Design. In: 2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), 98-102. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICALT49669.2020.00037

Behl, A., Jayawardena, N., Pereira, V., Islam, N., Del Giudice, M. and J. Choudrie (2022): Gamification and e-learnings for young learners: A systematic literature review, bibliometric analysis, and future research agenda. In: Technological Forecasting and Social Change 176, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121445

Bereitschaft, B. (2021): Commercial city building games as pedagogical tools: what we have learned? In: Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2021.2007524

Biró, G. I. (2014): Didactics 2.0: A Pedagogical Analysis of Gamification Theory from a Comparative Perspective with a special View to the Components of Learning. In: Proceedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 141, 148-151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.027

Bottino, R. (2019): Computers in Primary Schools, Educational Games. In: Tatnall, A. (eds.): Encyclopedia of Education and Information Technologies. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60013-0

Breien, F. S. and B. Wasson (2020) – Narrative categorization in digital game-based learning: Engagement, motivation & learning. In: British Journal of Educational Technology, Vol. 52, Nr. 1, 91-111. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13004

Bröker, T., Voit, T., and B. Zinger (2021): Gaming the System: Neue Perspektiven auf das Lernen. In: Hochschulforum Digitalisierung (eds.): Digitalisierung in Studium und Lehre gemeinsam gestalten. Innovative Formate, Strategien und Netzwerke. Wiesbaden: Springer, 497-513. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32849-8_28

Charsky, D. (2010): From Edutainment to Serious Games: A Change in the Use of Game Characteristics. In: Games and Culture Vol. 5, Nr. 2, 177-198. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412009354727

Czauderna, A. and A. Budke (2022): Players’ Reflections on Digital Games as a Medium for Education: Results from a Qualitative Study. In: Proceedings of the 16th European Conference on Game Based Learning Vol. 16, Nr. 1, 180-188. https://doi.org/10.34190/ecgbl.16.1.324

Czauderna, A. and A. Budke (2021): Game Designer als Akteure der politischen Bildung. In: MedienPädagogik 28, 94-116. https://doi.org/10.21240/mpaed/38/2021.01.25.X

Czauderna, A. and E. Guardiola (2019): The Gameplay Loop Methodology as a Tool for Educational Game Design. In: The Electronic Journal of e-Learning Vol. 17, Nr. 3, 207-221. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1237339.pdf

duolingo (2023): duolingo. https://www.duolingo.com

Ermi, L. and F. Mäyrä (2011): Fundamental Components of the Gameplay Experience. Analysing Immersion. In: Günzel, S., Liebe, M. and D. Mersch (eds.): DIAREC Keynote-Lectures 2009/10. Potsdam: University Press, 88-115. https://d-nb.info/1218392622/34

Feulner, B. (2021): SpielRäume. Eine DBR-Studie zum mobilen ortsbezogenen Lernen mit Geogames (=Geographiedidaktische Forschungen 73). Dortmund: readbox unipress. https://geographiedidaktische-forschungen.de/wp-content/uploads/GDF-73-Feulner-SpielRaeume.pdf

Free Lives (2023): Terra Nil. https://freelives.net/terra-nil/

Gryl, I. (2022): Spaces, Landscapes and Games: The Case of (Geography) Education Using the Example of Spatial Citizenship and Education for Innovativeness. In: Edler, D. Kühne, O. and C. Jenal (Eds.): The Social Construction of Landscape in Games. Wiesbaden: Springer, 359-376. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35403-9_21

Hemmer, M. (1996): Grundzüge einer Exkursionsdidaktik und -methodik. In: Bauch, J. and I. Hemmer (Hg.): Exkursionen im Naturpark Altmühltal. Eichstätt: Informations- und Umweltzentrum Naturpark Altmühltal, S. 9-16. https://www.ku.de/mgf/geographie/didaktik/forschung/abgeschlossene-projekte/exkursionen-im-naturpark-altmuehltal

Hensel, T. (2012): Das Computerspiel als Bildmedium. In: Games Coop (Ed.): Theorien des Computerspiels. Zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius, 128-146.

Hiller, J., Lude, A. and S. Schuler (2019): ExpeditioN Stadt. Didaktisches Handbuch zur Gestaltung von digitalen Rallyes und Lehrpfaden zur nachhaltigen Stadtentwicklung mit Umsetzungsbeispielen aus Ludwigsburg. Ludwigsburg: PH Ludwigsburg. https://phbl-opus.phlb.de/frontdoor/deliver/index/docId/620/file/Hiller_Lude_Schuler_2019_digitale-Stadtrallyes.pdf

Lämmchen, R. and S. Pietsch (2023): Digitale Spiele. In: Schreiber, V., and Nöthen, E. (eds.): Transformative Geographische Bildung. Schlüsselprobleme, Theoriezugänge, Forschungsweise, Vermittlungspraktiken. Wiesbaden: Springer, 289-294. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-66482-7_40

Lämmchen, R., Pietsch, S. and U. Wardenga (2022): Grundbegriffe digitaler, spielerischer und ortsbezogener Wissensvermittlung. Eine Handreichung des Projekts SpielRäume – Entdeckungs- und Erlebnisraum Landschaft. Leipzig: Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde. https://leibniz-ifl.de/fileadmin/download/SpielRäume2_Grundbegriffe.pdf

Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde (2023): SpielRäume – Entdeckungs- und Erlebnisraum Landschaft. https://leibniz-ifl.de/forschung/projekt/spielraeume-entdeckungs-und-erlebnisraum-landschaft

Leorke, D. (2019): Location-Based Gaming. Play in Public Space. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0683-9

Locandy (2023): Referenzen. https://multimedia-audioguide.locandy.com/referenzen/

Lux, J.-D. and A. Budke (2020): Alles nur ein Spiel? Geographisches Fachwissen zu aktuellen gesellschaftlichen Herausforderungen in digitalen Spielen. In: GW-Unterricht 160, 22-36. https://doi.org/10.1553/gw-unterricht160s22

Martin, M. W. and Y. Shen (2014): The Effects of Game Design on Learning Outcomes. In: Computers in the Schools. Interdisciplinary Journal of Practice, Theory, and Applied Research, Vol. 31, Nr. 1-2, 23-42. https://doi.org/10.1080/07380569.2014.879684

Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest (2022): JIM Jugendstudie 2022. Jugend, Information, Medien. Stuttgart: Medienpädagogischer Forschungsverbund Südwest. https://www.mpfs.de/fileadmin/files/Studien/JIM/2022/JIM_2022_Web_final.pdf

Pietsch, S., Lämmchen, R., and U. Wardenga (2022): Workflow zur Erstellung digitaler Exkursionsspiele. Eine Handreichung des Projekts SpielRäume – Entdeckungs- und Erlebnisraum Landschaft. Leipzig: Leibniz-Institut für Länderkunde. https://leibniz-ifl.de/fileadmin/download/SpielRäume3_Workflow.pdf

Pietsch, S. (2022): Anthropogener Klimawandel und das Schiffshebewerk Niederfinow. Spielerische Wissensvermittlung im Kontext ortsbezogener Climate-Fiction. In: Berichte. Geographie und Landeskunde, Band 95, Heft 3, 268-287. https://doi.org/10.25162/bgl-2022-0014

Robinson, G. M., Hardman, M. and R. J. Matley (2021): Using games in geographical and planning-related teaching: Serious games, edutainment, board games and role-play. In: Social Sciences & Humanities Open 4, Article 100208, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100208

Sailer, M. (2017): Die Wirkung von Gamification auf Motivation und Leistung. Empirische Studie im Kontext manueller Arbeitsprozesse. Wiesbaden: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-14309-1

Sanchez, E. (2019): Game-Based Learning. In: Tatnall, A. (Ed.): Encyclopedia of Education and Information Technologies. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-60013-0_39-2

Shen, C., Wang, H. and U. Ritterfeld (2009): Serious Games and Seriously Fun Games. Can They Be One and the Same? In: Ritterfeld, U., Cody, M. and P. Vorderer (Eds.): Serious Games. Mechanism and Effects. New York: Routledge, 48-61. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203891650

Stintzing, M. and S. Pietsch (2021): SpielRäume. Landschaft im Kontext digitaler Vermittlung multi-perspektivisch erfahren? In: Wintzer, J., Mossig, I. & A. Hof (Eds.): Prinzipien, Strukturen und Praktiken geographischer Hochschullehre. Bern: Haupt, 353-366. https://doi.org/10.36198/9783838556680

Tecvia (2023): Fahren Lernen Max. URL: https://www.fahren-lernen.de/de/fahren-lernen-max

Tolks, D. and M. Sailer (2021): Gamification als didaktisches Mittel in der Hochschulbildung. In: Hochschulforum Digitalisierung (Ed.): Digitalisierung in Studium und Lehre gemeinsam gestalten. Innovative Formate, Strategien und Netzwerke. Wiesbaden: Springer, 515-532. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-32849-8_29

Van Eck, Richard (2015): Digital Game-Based Learning: Still Restless, After All These Years. In: EDUCAUSE Review 50, Nr. 6, 12–28. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2015/10/digital-game-based-learning-still-restless-after-all-these-years

Van Eck, R. (2006): Digital Game-Based Learning. It`s Not Just the Digital Natives Who Are Restless. In: EDUCAUSE Review 41, Nr. 2, 16-30. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2006/3/digital-gamebased-learning-its-not-just-the-digital-natives-who-are-restless

Leave a Reply