Doing Film Geographies with the Video Documentary Approach

Authors:

Paul Hummel, Elisabeth Sommerlad, Julian Zschocke

Citation:

Hummel, Paul; Sommerlad, Elisabeth; Zschocke, Julian (2024): Video Documentary. Doing Film Geographies with the Video Documentary Approach. In: VisQual Methodbox, URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2024/03/21/video-documentary/

Essentials

- Trajectory: Audiovisual methods have become an integral part of today’s geographic methodologies.

- Data variety: Doing film geography using the approach of video documentary allows to cover a wide range of data and information.

- Scope: The combination of image and sound characterizes the medium of film. Therefore, the strengths of using film as method lie in the possibility to convey environments, emotions, and other experiences in a unique way. Film itself can be considered a social practice that continues to focus not only on representations, but on what representations do and how (Lukinbeal & Sommerlad, 2021).

- Mixed Methods: Can be mixed with other qualitative methods such as expert interviews, participatory observation, or atmospheric research.

- Challenges: … lie in the complexity of the method, a higher barrier of entry and technical obstacles.

Description

The production of video documentaries is a creative empirical method, which more and more geographers embrace as a way of approaching qualitative research. While it is rather hard to define what constitutes a documentary, there is a famous quote from filmmaker John Grierson, allegedly the inventor of the term ‘documentary’ (Deacon, 2006). In 1926, he stated that documentary-filmmaking is “the creative treatment of actuality”.

Making films can be a method for conducting geographic field research, rooted in the broader framework of film geography. As a subdiscipline of media geography, film geography focusses on the interaction between geographical and filmic contexts. From a more traditional point of view, film geography deals with the multi-layered geographical imaginations in film and the connections and effects on our everyday world (Zimmermann, 2009). Alongside the study of cinematic representations of space and place, the “geography in film” (e.g., discourses on the cinematic city), film geographers also deal with the “geography of film” (e.g., film industry geographies, effects of media tourism). In addition, critical perspectives on the medium have increasingly developed in recent years and geographers have also become interested in reception and reflection contexts, for example in relation to pedagogical matters and film reception (Sommerlad, 2021).

There have been emerging tendencies in social and cultural science research for several years now to work not only analytically but also methodically with (audio)visual materials (Rose, 2023). Film geography picks up on this by calling for “doing film geography” (Jacobs, 2013, 2016, Roberts, 2020, Lukinbeal & Sommerlad, 2022). Thus, an applied engagement with the medium a is increasingly becoming the focus of geographic engagement with film; merely the utilization of film as a research method, medium of scholarly communication and research output.

As Garrett (2010, p. 536) points out, integrating film and video production into the methodological toolbox opens up new and exciting possibilities for research: “Videographic work gives researchers an avenue to depict place, culture, society, gesture, movement, rhythm and flow in new and exciting ways.” Interaction with audiovisual content enables new possibilities – but also challenges – of capturing, reproducing, interpreting, and further developing spatial complexities. “Doing film geography” opens geographies beyond the written word. Geographers can thus gain new insights into the spatial through an applied perspective on or practical engagement with film(s), which enriches geographical knowledge production (Knoblauch & Schnettler, 2012).

The method of video documentary is ideally suited to respond to Singer, Schmidt & Neuburger’s (2023) call for a creative (re-)turn in human geography, which shifts geographical perspectives towards creative and emotional approaches to knowledge and scholarship. This is particularly evident when participatory aspects are incorporated into the film as methodological approach, or when a film is challenging established perspectives in a quasi-activist manner. An excellent example of this are three short films made by a collective centred around geographer Alice Salimbeni, in which the filmmakers deal with the appropriation of urban spaces from a feminist perspective (Salimbeni, 2022; the paper contains permanent links to the films on Vimeo).

However, engaging with filmmaking practices may involve challenges. The complexity and technical requirements to apply the method can be time-consuming and financially demanding – an aspect that should be considered as early as possible in the research process. Bear in mind that recording videographic data can interfere with privacy rights and lead to (un-)ethical challenges. Written consent should therefore be obtained where possible to consent to the film recordings. Furthermore, it should be remembered that not everyone wants to become “identifiable” through the (audio)visual and that there might occur cultural challenges when using videography for documenting sensitive environments (Özgür, 2022).

Procedure

While the process of filmmaking itself can take many shapes or forms, we will outline what to consider in a three-step approach to filmmaking:

Preproduction:

Preproduction starts with an idea of which topics to tackle, to research, and to portray in the film. In this phase, a pitch, treatment, and/or script can be developed to outline the plot and themes of the movie. While this process is highly creative, there are also organizational hurdles that need to be taken care of. For instance: Is a budget available and what does it account for? Which equipment is necessary to shoot the film? Where and when will shooting take place? Do appointments have to be scheduled for interviews, locations, events etc. (Cartwright, 1996).

Production

Production encompasses the actual recording of the footage (Brown, 2016). With smartphone cameras becoming widely available, a new one-person style of video shoot with a phone as a recording tool has risen in popularity due to its comparatively low barrier of entry. This style is recommended for beginner filmmakers. When shooting on a phone, we recommend an advanced camera app like Filmic Pro that allows to manually control recording parameters. If the final film should be uploaded to a platform like YouTube or Vimeo, it is recommended to apply the following video-settings for the smartphone / camera:

A lot of things happen at the same time during film production and therefore need to be taken care of, which is why film crews in a more advanced setting are usually made up of multiple people handling different aspects of the audiovisual recording (Alfarraji & Al Smadi, 2023). Camera operation, sound recording, lighting, acting, interviewing, hosting, and data handling are some exemplary tasks on the days of shooting (Brown, 2016).

Postproduction

Postproduction is the process of selecting, understanding, and editing your data, including splicing together your footage in a coherent matter, or adding and substracting from the originally recorded sequences (Pratt, 2007). This step is crucial as it implements the thoughts and considerations of the filmmaker. As part of this process, the collected empirical data is analyzed, interpreted, and situated within theoretical concepts, similar to coding processes in social science research.

Postproduction is a time consuming and demanding task that significantly shapes the narratives and messages of the conducted research. Editing can be done on mobile devices with dedicated apps like Kinestar or in non-linear editing software for computers like Premiere Pro or DaVinci Resolve. Postproduction necessitates an understanding of the software as well as dedicated hardware since video-editing is rather demanding on the Graphics Processor (GPU).

Within the editing-process, alterations to the material will significantly shape the recipient’s perception of the footage: in which order do things appear, which music and sounds are added to scenes, how are in-image effects used, or narrative questions like which context is given or left out in any situation.

Example – Raíces y Brotes (2023)

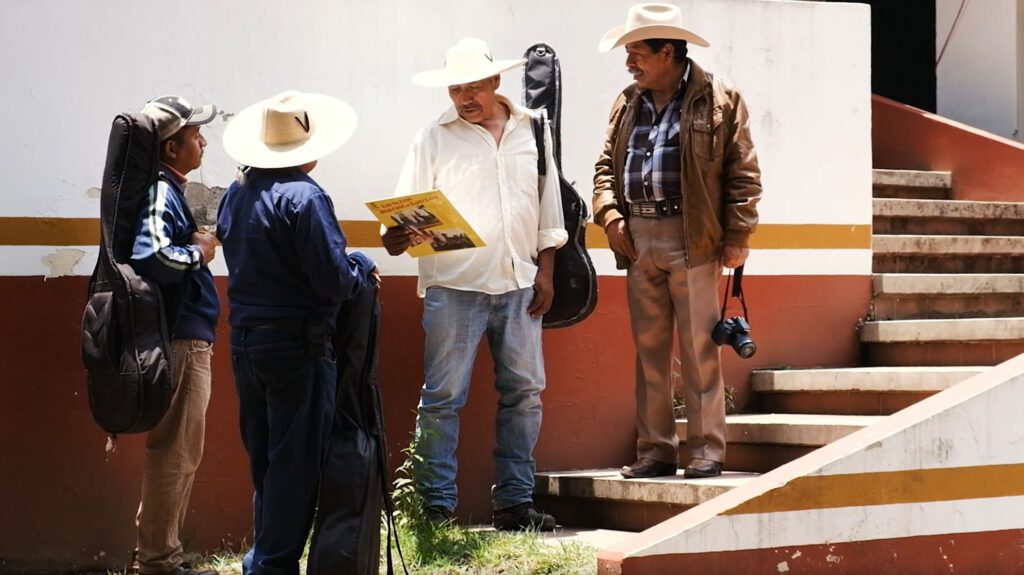

As an example, we want to introduce the geographic documentary “Raíces y Brotes” (2023) which was produced as a master thesis in the context of our master program “Human Geography: Globalisation, Media and Culture” at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. In the documentary, geographic filmmaker Paul Hummel investigates the strong relationship between music and a newly emerging political self-confidence of the indigenous group P’urhépecha in Mexico. Rural communities have created “autogobiernos” in which they are experimenting with different forms of community-based governance rooted in their own normative system. They are focusing on a return to their own traditional values, former lifestyles and world views, which are embraced by the term “Usos y Costumbres” (Usages and Customs) that are consulted as a basis for the negotiation of indigenousness. Spurred on by political movements in the last decade, local musicians, activists, and artists are now using multiple forms of self-expression to shape their indigenous perspective. Their music is now supposed to represent self-chosen ideas for a free and self-determined life. However, after a multitude of debates, it is yet unclear how this is exactly to be lived out. Although music is not necessarily perceived as political, it can mediate a renegotiation of a collective political identity. Here is a field report on Paul’s filming experience:

Fig. 1: Behind the Scenes – Interview with music activist Luis (Foto: Paul Hummel)

For my 6 weeks of field work in Mexico, I had to find an approach to the traditional music of the P’urhépecha in the context of political autonomy. I chose film as the method because an abstract concept of identity could be visualized, and the subject could thus be kept interpretative and open. At the same time, film depicts the music in its acoustic entirety without paraphrasing. For this purpose, I conducted numerous expert interviews and filmed musicians who were in contact with the research topic. The project relied on Jones’ (2005) ideas of a free and open-minded approach to Grounded Theory as well as of MacDougall’s (2019) philosophy: „To find new bearings, one may need to get a little lost” (MacDougall 2019, p. 13). I thought that the challenge with this approach is that it requires a certain amount of confidence and structure and I was concerned ending up with no usable material.After the first interviews, however, I quickly realized that the approach didn’t limit me but gave me the creative freedom I needed. Afterwards, it was a lot of fun.

Fig. 2: Behind the Scenes – Live Music Recording with “Chilo” (Foto: Paul Hummel)

Fig.3: Main camera – Interview with music teacher “Chilo” (Foto: Paul Hummel)

Before the fieldwork, I had to organize my trip. I made a rough financial assessment of the required budget (travel costs, equipment cost, insurance) which made it necessary to apply for funding at the university. Also, the selection of the strategic location to organize the shooting days on-site and establishing a first contact with the community was essential. As specific types of film narration require special types of shots, I made a small script of how I want my shots to be filmed (e.g. 1st person, 3rd person perspectives, B-Roll). The media platform milanote.com helped gathering screenshots I took from other documentaries for inspiration. This is important to keep in mind not only for aesthetic considerations but also in understanding how meta levels can be created to visualize the processes behind the camera. In test shootings with friends and family I experienced, that the writing speed of some SD cards was too slow for HD recordings that last longer than a couple of minutes. This needed to be fixed beforehand by swapping out the SD cards.

Fig. 4: Behind the Scenes – Interview with Pireri Miriam (Foto: Paul Hummel)

Fig. 5 Main Camera – Interview with Pireri Miriam (Foto: Paul Hummel)

During a shooting period, 100 hours of film material were gathered covering 19 semi-structured expert interviews and B-Roll material. The selection of shooting places and interviewees was previously agreed after consultation with a local activist who co-hosted the filming process. As hardware, I took two digital cameras on tripods set to Full-HD with a frame rate of 25fps, as well as two lavalier microphones connected to each camera. Additionally, I took an atmospheric microphone to record soundscapes after the interviews that I could use later as background sounds to overwrite sound cuts. The technical barriers to the hardware had to be assessed in advance so that during the shooting no technical issues would disturb the process. Challenging technical obstacles were for example clipping microphones, unfocussed shots, too dark or too bright shots or overheating cameras in direct exposure to the sun. Before filming, I think that a test run with all available materials is very important. There are so many things to be considered during shooting and you don’t want to worry too much about how your equipment works.

After the postproduction, I had a 47-minute documentary film, which depicts an entrance to the complex debates that took place in the community. Afterwards, the documentary was screened in several communities and congresses, which I attended online, and a debate took place about its content. It was published on YouTube, respecting copyright, and data protection issues. The film’s content was meant to fulfill tree purposes: a) to understand the complex political dynamics in the region from an outsider’s perspective and to identify narratives in and around music, b) to produce a research result that enriches the geographic debates about political identity and music, c) to experiment with applied film research methods for new academic toolboxes. Of course, one of my goals was to complete my master’s degree, which should be mentioned, too.

Fig. 6: Main camera – Shooting Day at Radio XEPUR (Foto: Paul Hummel)

Evaluation

Collecting videographic data in a research process opens up new opportunities for researchers “to depict place, culture, society, gesture, movement, rhythm and flow in new and exciting ways” (Garrett, 2010, p. 536; Knoblauch & Schnettler, 2012). The use of film documentary as a method is suitable for visualizing qualitative research data in multiple ways (Roberts, 2020; Gandy, 2021; Lukinbeal & Sommerlad, 2022). The method is suitable for communicating research results, i.e. for communicating cinematic geographies and reaching a wider audience. Film can also be used in the context of data collection; for example, short film clips can be used as a stimulus in interview settings. Moreover, video material can be produced in the context of participatory research – interview partners can be asked to capture their own footage to visualize individual perspectives on spatial settings – like reflexive photography, or to critically engage with the power relations embedded in (documentary) films (Özgür, 2022).

Videography and/or the production of (documentary) film to communicate research outputs involves technical challenges that need to be considered during preparation. Planning for sufficient time is crucial – both when recording data (a process that must be well prepared to generate adequate footage and B-roll material) and in post-production. In addition, researchers should also critically engage with ethical questions of research and reflect on their own powerful positionality when opting for this method. It is indispensable to review methodological implications of the medium and to develop a particular level of audiovisual media competence (Thieme et al., 2019, Jacobs, 2013; Lukinbeal, 2014; Lukinbeal et al., 2007, 2015).

Useful Resources

- Hummel, P. (2023) Raíces y Brotes – P’urhépechan Music, Politics & Identity. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4D74iCH30yU (22.3.2024)

- “Film Geographies” (www.filmgeographies.com): The platform launched by Jessica Jacobs and Joseph Palis curates international films of various kinds that communicate cinematic geographies (e.g. documentaries, short films, fictional films, etc.). The network regularly calls for participation in academic film competitions (e.g. RGS-IBG, AAG) and organizes workshops and discussions on the topic.

- The publication “Visual Methodologies” by Gilian Rose, now in its fifth edition, offers a comprehensive introduction to visual methods in geography and social sciences. The book is accompanied by a website companion with numerous supplementary materials and helpful exercises to practice the methods. https://study.sagepub.com/rose4e/student-resources

- The documentary film “And the King Said, What a Fantastic Machine” (2023, directed by Axel Danielson, Maximilien Van Aertryck, Sweden) takes a critical look at the medium of the camera and considers both historical contexts and contemporary trends. It is an excellent way of gaining an overview of media-cultural perspectives and moving images:

Suggested Hardware

- Filming for everyone: Smartphone

- Easy to use, semi-professional camera: Sony ZV1-II

- Advanced DSLR, professional camera: Fujifilm X-H2S, Blackmagic Pocket

- Interview Sound: Rode Go Mic and Lavalier microphone (interview situations)

- Atmospheric Microphone: Zoom H6N, Tascam DR40-X

Suggested Software

- Smartphone filming: Filmic Pro (app)

- Smartphone editing: Kinestar (app)

- Professional, non-linear editing: Premiere Pro or DaVinci Resolve

References

Alfarraji, K. & M. Al Smadi (2023): Role Of The Production Designer. In: Filmmaking – The Pre-Production Of Narrative Film As A Case Study. Journal of Namibian Studies: History Politics Culture, 33, 5651-5680. https://doi.org/10.59670/jns.v33i.1883

Brown, B. (2016): Cinematography: Theory and Practice: Image Making for Cinematographers and Directors. Taylor & Francis, London. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315667829

Cartwright, S. (1996): Pre-Production Planning for Video, Film, and Multimedia. Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780080927152

Deacon, D. (2006): ‘Films as foreign offices’: transnationalism at Paramount in the twenties and early thirties. In: Curthoys, A. & M. Lake (Eds.): Connected Worlds: History in Transnational Perspective. Canberra, ANU E Press: pp. 139-156. https://doi.org/10.26530/oapen_458894

Gandy, M. (2021): Film as Method in the Geohumanities. GeoHumanities, 7(2), pp. 605–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2021.1898287

Garrett, B. (2010): Videographic geographies: Using digital video for geographic research. Progress in Human Geography, 35(4), p. 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132510388337

Hawkins, H. (2011). Dialogues and Doings: Sketching the Relationships Between Geography and Art. Geography Compass, 5(7), 464–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2011.00429.x

Jacobs, J. (2016): Filmic geographies: The rise of digital film as a research method and output. Area, 48(4), pp. 452–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/area.12309

Jacobs, J. (2013): Listen with your eyes; towards a filmic geography. Geography Compass, 7(10), pp. 714–728. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12073

Jones, M. (2005): ’Lights… Action… Grounded Theory’: Developing an understanding for the management of film production. Faculty of Commerce – Papers, 1(1), 143–153.

Knoblauch, H. and B. Schnettler (2012): Videography: Analysing video data as a “focused” ethnographic and hermeneutical exercise. Qualitative Research, 12(3), pp. 334–356. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111436147

Lukinbeal, C. (2014): Geographic media literacy. Journal of Geography, 113(2), pp. 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221341.2013.846395

Lukinbeal, C., Finn, J., Jones, J., Kennedy, C., and K. Woodward (2015): Mediated geographies across Arizona: learning literacy skills through filmmaking. In: Mains, S., J. Cupples, and C. Lukinbeal (Eds.): Mediated geographies and geographies of media. Dordrecht, pp. 401–416. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9969-0_24

Lukinbeal, C., Kennedy, C. B., Jones, J. P., Finn, J., Woodward, K., Nelson, D. A., Grant, Z. A., Antonopoulos, N., Palos, A., and C. Atkinson-Palombo (2007): Mediated geographies: Critical pedagogy and geographic education. Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, 69(1), pp. 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1353/pcg.2007.0009

Lukinbeal, C. and Sommerlad, E. (2022): Doing Film Geography. GeoJournal 87 (suppl. 1), pp. 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10651-2

MacDougall, D. (2019): The looking machine: Essays on cinema, anthropology and documentary filmmaking. Anthropology, creative practice and ethnography. Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526134103

Özgür; Ö. A. (2022): Refugees re-making community: on the performativity of participatory video. GeoJournal 87 (Suppl. 1), pp. 63-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-022-10655-y

Pratt, S. (2007): ‘Imagination can be a damned curse in this country’: Material geographies of filmmaking and the rural. In: Fish, R. (Ed.): Cinematic countrysides. Manchester, Manchester University Press: pp. 127-146.

Roberts, L. (2020): Navigating cinematic geographies: Reflections on film as spatial practice. In: Edensor, T., Kalandides, A., and U. Kothari (Eds.): The Routledge handbook of place. Milton Park, pp. 655–663.

Rose, G. (2023): Visual Methodologies. An Introduction to Researching with Visual Materials. Oxford.

Salimbeni, A. (2022): Urban Piss-Ups. The collective filmmaking of parodic urban fables to study and contest gender spatial discriminations. Gender, Place & Culture 20 (12): 1759-1784. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2022.2118242

Sommerlad, E. (2021): Film geography. In: Adams, P.C. and B. Warf (Eds.), Routledge handbook of media geographies. Milton Park, pp. 118–131.

Singer, K., Schmidt, K. & Neuburger, M. (Ed.) (2023): Artographies – Kreativ-künstlerische Zugänge zu einer machtkritischen Raumforschung. Transcript, Bielefeld. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839467763

Thieme, S., Eyer, P., and A. Vorbrugg (2019): Film VerORTen: Film als Forschungs und Kommunikationsmedium in der Geographie. Geographica Helvetica, 74(4), pp. 293–297. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-74-293-2019

Zimmermann, S. (2009): Filmgeographie: Die Welt in 24 Frames. In: Döring, J. and T. Thielmann (Eds.): Mediengeographie. Theorie—Analyse—Diskussion. Bielefeld, pp. 291–314.

Leave a Reply