Enactment and Experience of Embodied Images

Author:

Sophia Feige

Citation:

Feige, Sophia (2024): Freeze Frames: Enactment and Experience of Embodied Images. In: VisQual Methodbox, URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2024/02/28/freeze-frames/

Essentials

- Bildungsprozesse (educational processes): This method is based on a theoretical approach towards Bildung as a non-linear process which cannot be guaranteed by giving a certain input and expecting a suitable outcome. The Bildungsprozesse that freeze frames can help to initiate are based on the theoretical works of Dörpinghaus (2005), Koller (2023) and Sabisch (2020).

- Performance: Derived from Theatre studies, performance is defined as enacting what is meant (Fischer-Lichte 2012:45). Therefore, performances always refer to themselves and constitute reality (ebd.). They include symbolic as well as embodied dimensions of meaning.

- Aesthetic experience: In order for an aesthetic impression to become an aesthetic experience, it needs to be reflected by the self who goes through the experience (Hasse 2007:5). Aesthetic experiences can initiate Bildungsprozesse.

Description

Freeze frames put a stop on otherwise fleeting impressions such as movie scenes, video clips, thoughts, social situations and theatrical performances. In a nutshell, freeze frames are scenes which show significant interactions between characters or key moments of the plot. These scenes are selected and recreated by participants in order to freeze them in time and to enable observers to experience the embodied images (Scheller 2008:72).

The imagery of freeze frames enables both the actors and the observers to experience a profound involvement instead of only catching a short glimpse of the scene. These moments of deceleration are described by Dörpinghaus as a potential starting point for Bildungsprozesse (2005:566). A profound involvement means to focus one’s own perception on irritations, disruptions and questions which arise when we reflect on things that initially seem to be natural in the dynamic scene before freezing it (ebd.). Both the moment of deceleration and the enabled questionability offer the potential to transform fundamental figures of the relation between oneself and the world and are therefore requirements for what Koller calls transformative Bildung (2023:15). In addition, Andrea Sabisch (2020:103) suggests to include performative dimensions into the idea of transformative Bildung.

A performative and phenomenological approach to the pedagogical value of freeze frames focuses, similar to an approach to pictures, on their emergence, or on the how rather than on the product or the what (Schlottmann & Miggelbrink 2015:16). This means that freeze frames themselves are not much of an analytical tool but rather a method which depicts interactional processes of production and may lead to educational processes.

When participants create an embodied image from media scenes, they are confronted with the task of changing a dynamic scene into a static performance. Nevertheless, the static performance of a freeze frame has to be enacted and therefore the actors need to make several analytically relevant choices. On one hand, enacting a scene means to carefully consider facial and bodily forms of expression, spatial arrangements and the viewers point of perception. On the other hand, however, unpredictable phenomena occur within the enactment (Fischer-Lichte 2012:75), such as a comical appearance of a seriously enacted scene, a sudden feeling of oppression in a scene supposed to show a friendly relationship or a completely new meaning of a scene no one thought about before enacting the freeze frame. Those unpredictable phenomena can change the enactment in a way which cannot be intended by the actors and are therefore emergent properties of the process and product (ebd.). Not only are they not intended, but they do also point to the loss of agency of the actors in the process of enactment which is also called the pathic dimension of the performance (ebd.:87).

Similar to their enactment, the perception of freeze frames does include the consideration of the intended symbolism as well as the unpredictable emergence of phenomena (Fischer-Lichte 2012:101). Intended symbols are perceived by the observers just as the actors want them to be perceived, for example a smiling face which is a symbol for a happy person and is perceived as such by the observer. In contrast, a smiling face could also lead to unpredictable emotions such as anger or sadness because of the observer’s perspective, a sudden feeling of unease or an impulse to mimic the smile. Since these phenomena are unpredictable, the ways in which experience that lead to Bildungsprozesse are made by the participants cannot be described or implemented with linear input and output figures (Dörpinghaus 2005:573). Instead, practical considerations of faciliations need to take the participants in their anthropologic and embodied dimensions into account. Such a consideration includes taking the participants serious as human beings as well as supporting an open and mindful attitude in the process of creating freeze frames. When the participants create and encounter the freeze frames, they participate in an aesthetic experience (Hasse 2007:6). Such an experience can lead to Bildung, when the participants start to reflect on the freeze frame as well as themselves as actors and observers (ebd.).

Since freeze frames are embodied images, they take a special place between an object-like imagery and a subjective embodiment. This offers the potential to focus on both the different ways on how to approach them as a picture and the bodily capabilities which are used to create them. Basically, freeze frames are a method of expression and reflection: The decisions which lead to the enacted freeze frames and the perception of them highly depend on the participants and can help them to express their understanding, emotions and attitudes towards a scene. Freeze frames can be used in order to reflect on impressions and thoughts about otherwise dynamic scenes when working with media regarding their content (Scheller 2008:72). Nevertheless, freeze frames are a method which requires a high degree of empathy and a trusted atmosphere between teachers and participants. If participants refuse to express themselves in such a way or feel beset by the task, one should consider using methods with a lower degree of bodily involvement and expressiveness.

Procedure

The following description of how to implement freeze frames is primarily based on the description of the method by Scheller (1999:59ff.) and the reflection on how to work with the imagery of images by Dickel & Pettig (2017:264f.).

- Step 1: Deciding on a scene

The scene from which a freeze frame is created can be given or chosen by the participants. This may be a scene based on the participants’ livelihood and experiences, or fictional scenes. In a first step they have to decide on what they want to express with their freeze frame: Is it about a reflection on a certain act or interaction? Do they want to appraise or to criticize a certain character or interaction between characters from the scene? Is there a moment which should be taken into close consideration by the observers?

- Step 2: Building the freeze frame

Depending on the size of the group, either all of its members participate in the freeze frame or a director is chosen from the group who does not participate in the freeze frame itself but provides instructions for the actors. Together the group reflects on how to express their thoughts, attitudes and feelings in the freeze frame and how to use their facial and bodily expressions at the moment of freezing. The groups then agree on a chronological order and freeze into the agreed frame one after another while the others observe.

- Step 3: Engaging with the freeze frame

When the group is frozen in their frame, the observers can start to engage with it. Firstly, they try to understand the concept of the emerged image: They consider their first impression, the general structure of the picture, and walk around it in order to look at it from different perspectives. This first substep focuses on the technical and formal set-up of the frame. Secondly, the participants try to understand their own perception of the picture. This includes the pathic dimension of perception and therefore asks how the encounter between the image and the observer is constituted instead of asking for an interpretation. Finally, in a third substep, the participants try to understand their own aesthetic experience. They focus on their embodiment as well as on the embodiment of the freeze frame. This means that they comprehend how their impression of the freeze frame changes when they move around and change their perspective. Furthermore, they focus on their bodily impressions: Do they feel comfortable or uneasy when looking at the frame? Is there something that catches their interest or irritates them?

- Step 4: Reflecting on the experience

The main aspect of this key step is to verbalize the experience made in the previous steps amongst the group. The imagery of the freeze frames creates a heterogenous approach to the production of space between the image and the observers. Some of the observers will recognize the intended symbols and focus on them, others will focus on irritations or frictions that were not intended by the actors. Some might feel moved, or the freeze frame makes them wonder, others will not feel emotional at all. The individual approaches depend on the attitude and previous experiences of the observers but also on the way of approaching the freeze frames in space. It is crucial to verbalize expectations, preconceptions, perceptions, and emotions towards the freeze frames. After thinking about and verbalizing these impressions, the participants can start a dialogue and exchange their impressions within small groups. This socio-spatial process reveals inconsistencies, accordances, unexpected readings, and connections between the embodiment of the scene and the imagery of the freeze frame. The groups may also write down their discussions and use them for a dialogue with the whole group.

Requirements

- a group of at least 8 participants and a teacher/supervisor

- a room with enough space to roam freely and build the freeze frames

- a calm and open atmosphere created by mutual respect and mindfulness

Example

In November ’22, a group of teacher trainees of geography used the freeze frame method in a seminar. The elective module addressed a critical approach towards the life and achievements of Alexander von Humboldt, and of towards those who researched in scientific and belletristic ways about this famous figure of geographical science and history. In their practice session, they reviewed Die Vermessung der Welt by Daniel Kehlmann. The freeze frame method was specifically used in order to get into touch with key scenes of the story.

Figure 1: A dispute between Carl Friedrich Gauß (left) and Alexander von Humboldt (right) (Source: S. Feige)

Figure 1 freezes the moment of a dispute between Carl Friedrich Gauß and Alexander von Humboldt about how to practice natural sciences in the 19th century. Humboldt had a restless and lively urge to explore the physical world with measuring instruments as well as an aesthetic approach whereas Gauß measured the world from his desk and in a purely mathematical and analytical way. During the following reflection, the observers described the facial and bodily expressions of the actors in dichotomous conceptual pairs, e. g. sit – stand, look away – look at the other, calm – restless. They later discussed how the author of the book characterized these scholars, how the freeze frame embodied two different ideas about science at the time, and how those are embedded within the characters.

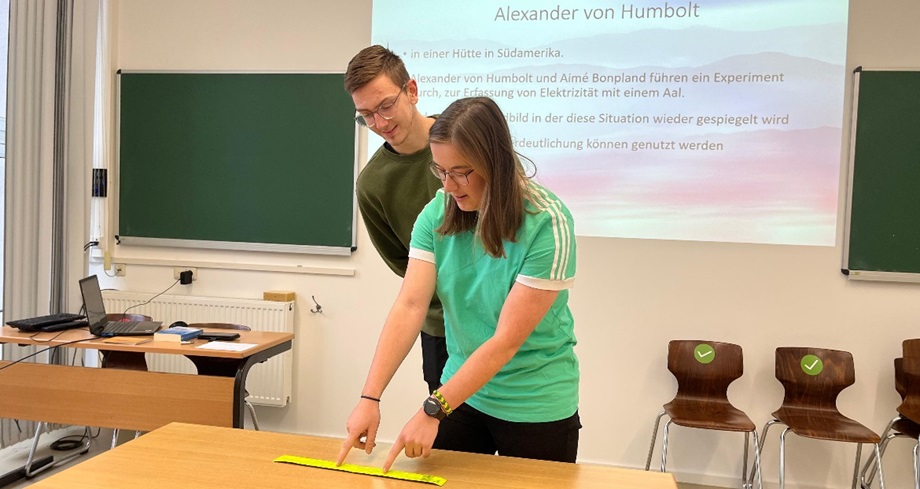

Figure 2: Alexander von Humboldt (right) and his travelling companion Aimé Bonpland (left) examine an electric eel (Source: S. Feige)

Figure 2 shows a scene from Alexander von Humboldt’s great American voyage (1799-1803). The actors present Humboldt’s examination of Electrophorus electricus, a species from the genus of electric eels. His travelling companion Aimé Bonpland watches Humboldt’s studies with interest, but without touching the eel by himself. Later, the actors described their struggle to find the perfect moment of freezing, weighing when the relationship between the two characters appeared like they wanted to represent it. The further discussion of the frame focused on the question of how to represent complex human interactional structures in a single image so that observers would be able to understand it. While reflecting on the complex relationship between Humboldt and Bonpland, they came into dialogue about general difficulties of human communication and started to describe situations in which they experienced those difficulties. This is an excellent example of how an unintended phenomenon (the friction between what the actors wanted to show about the two characters and how the observers experienced it) lead to a intensive reflection about how we interact with each other.

Suggested Tools

One of the major advantages of freeze frames is that they do not require any tools, digital platforms or materials other than the group itself. They can be used outside and indoors. In addition, props can be used but are not mandatory. Similar to improvisational theatres, props are usually made out of objects that are found spontaneously.

References

Dickel, M; F. Pettig (2017): Unheimliches Fukushima: Auf Streifzug durch die Geisterstadt Namie mit Google Street View. In: Jahnke, H., A. Schlottmann & M. Dickel (Hrsg.). Räume visualisieren. Geographiedidaktische Forschungen 62. Münster: readbox unipress in der readbox publishing GmbH. https://www.uni-muenster.de/imperia/md/content/geographiedidaktische-forschungen/pdfdok/gdf_62_jahnke_-_korr.pdf

Dörpinghaus, A. (2005): Bildung als Verzögerung: Über Zeitstrukturen von Bildungs- und Professionalisierungsprozessen. – Pädagogische Rundschau, 59, 563–574.

Fischer-Lichte, E. (2012): Performativität: Eine Einführung. Edition Kulturwissenschaft Bd. 10. Bielefeld: Transcript.

Hasse, J. (2007): Ästhetische Bildung: Eine doppelte Perspektive ganzheitlichen Lernens. – widerstreit sachunterricht, 8, 1–10. https://opendata.uni-halle.de/bitstream/1981185920/94477/1/sachunterricht_volume_0_5931.pdf

Koller, H.-C. (2023): Bildung anders denken: Einführung in die Theorie transformatorischer Bildungsprozesse. Stuttgart: W. Kohlhammer GmbH.

Sabisch, A. (2020): Zwischen Bildern und Betrachter*innen: Wie Bilder uns ausrichten. – Zeitschrift Kunst Medien Bildung, 103–115. https://zkmb.de/zwischen-bildern-und-betrachterinnen-wie-bilder-uns-ausrichten/?print=pdf

Scheller, I. (1999): Szenisches Spiel: Handbuch für die pädagogische Praxis. Berlin: Cornelsen Scriptor.

Scheller, I. (2008): Szenische Interpretation: Theorie und Praxis eines handlungs- und erfahrungsbezogenen Literaturunterrichts in Sekundarstufe I und II. Praxis Deutsch. Seelze: Kallmeyer in Verb. mit Klett.

Schlottmann, A; J. Miggelbrink (2015): Ausgangspunkte: Das Visuelle in der Geographie und ihrer Vermittlung. In: Schlottmann, A. & J. Miggelbrink (Hrsg.). Visuelle Geographien: Zur Produktion, Aneignung und Vermittlung von RaumBildern. Sozial- und Kulturgeographie 2. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 13–25.

Leave a Reply