Everyday Spaces and Emotions of Vulnerability

Authors:

Svenja Keitzel, Luise Klaus & Stella Schäfer

Citation:

Keitzel, S.; Klaus, L.; Schäfer, S. (2024): Emotional Mapping. Everyday Spaces and Emotions of Vulnerability. In: VisQual Methodbox, URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2023/12/19/emotional-mapping/

Essentials

- Nature: Qualitative interview method combined with a critical mapping approach

- Focus: Relationality of emotions, space, and power relations

- Benefit: Opens perspectives of people who experience vulnerability

Description

The purpose of Emotional Mapping is to show marginalised perspectives on space and to examine power relations in spaces (Germes & Klaus 2021). We use the method to research experienced encounters with authorities and institutions, or phenomena such as (domestic) violence. In this paper we present two variations of conducting interviews that a) explore everyday spaces and b) biographical paths.

Emotional Mapping is a qualitative interview method focusing on relationality of emotions, space, and power relations. We use the method to conduct interviews with people who experience vulnerability. We understand vulnerability as a socially unevenly distributed condition of life (conditio humana) that manifests in very different forms. Some people are more protected from vulnerability for example concerning bodily integrity, and others less so (Butler 2005: 49). With Emotional Mapping we aim to visualize the experiences of people who experience vulnerability by asking, for example, about their lived spaces, daily routines and transitions in life-courses. Furthermore, we ask which emotions they experience in these settings and spaces. Emotions are the “embodied experiences of social relations” (Laliberté & Schurr 2016, S. 74); in this understanding, emotions are lived experiences; therefore, we refrain from the dichotomic differentiation of emotions and affects (Schurr & Strüver 2016). In the process of visualization, the method grasps the sediments of materiality, discourse, institutions, power, and subjects.

Developed in the tradition of mental mapping, the method offers unique “cognitive representations” (Downs & Stea 2011, S. 313) of individuals spatial behaviour. The maps show the experienced space and connected emotions. They sometimes appear like a city plan, others show different sketches or mainly contain words and may have few or no drawn elements. The produced maps show particular and individual perspectives of lived spaces. They are “a lens into the way people produce and experience space, forms of spatial intelligence, and dynamics of human-environment relations” (Gieseking 2013). Rooted in feminist recognition like Donna Haraway’s work (1988), Emotional Mapping emphasises the importance of recognising that knowledge is always situated. Therefore, we reflect the positions of the researchers and the participants as well as the different positions within the participants (class, gender, race etc.). Furthermore, Emotional Mapping is a “storytelling device” (Campos-Delgado 2018, S. 490), which may enrich interviews. The method can help to break up a rigid interview setting and instead create a conversation of equals. The involvement of emotions helps us to understand the stickiness between materiality, discourse, power, and experiences (Ahmed 2004, S. 120).

Even if the method aims to dismantle power asymmetries, it is limited in doing so – it claims to be low threshold but remains partly demanding and preconditional: Firstly, a calm interview setting and a table on which to make the drawings are needed. These requirements are not inherently met in every situation, particularly when conducting research with individuals in vulnerable positions. Secondly, the interviewees need to understand the request to draw spaces of their lives. This task requires greater demands than mere storytelling in a qualitative interview and can trigger insecurities in the interviewee. This ultimately hints at the subtle power asymmetries present between participants and researchers, which the latter may need to reflect on and even counter in Emotional Mapping: For instance, we witnessed how interviewees repeatedly expressed concerns about not fulfilling the method’s (or the researcher’s) expectations. Furthermore, many were concerned about their ability to draw. Sometimes the participants needed constant encouragement while drawing. Thirdly, the interviewer should be empathetic and appreciative since the method touches on the topic of experiencing vulnerability. It can be useful to ask beforehand if the participant has certain topics that she/he does not want to talk about. In this way, questions in this direction can be avoided. This considerate approach helps ensure that the interview process is conducted in a compassionate and empathetic manner.

Procedure

The mapping takes the form of a qualitative guideline-based interview. During the interview, the interviewees draw spaces of importance to them on a white sheet of paper. In Variation A, places they visit every day and in Variation B, places that have been important to them in their life course. During a later phase of the interview, emotions are attributed to various locations, situations, or individuals depicted in the drawings.

Procedure Variation A: Everyday Spaces

- Step 1: Introduction/ Beginning of the interview

The first part of the interview is an introductory explanation of the interview and drawing technique. A range of questions might serve as narrative stimuli about everyday life and spaces of the interviewees. While inquiring about a person’s place of residence is a common approach, it is crucial for the researcher to exhibit exceptional sensitivity, as such an inquiry can potentially evoke distress or resurface traumatic memories for various reasons. For instance, when engaging with a person who might experience homelessness, instead to ask directly about their “home”, it is advisable to inquire about their current whereabouts or where they rest and sleep. - Step 2: The lived space/ The drawing

The first narratives and explanations about everyday life and spaces are accompanied by the request to draw these places and spaces and to locate them on the map. The interviewer may need to encourage or remind the interviewees to draw the places they are talking about. Nonetheless, it is crucial to reassure the interviewees that the map reflects their personal life and experiences. They maintain full autonomy over what to illustrate and the manner in which they choose to do so. - Step 3: Emotional spaces/ The Colouring

The third part of the interview asks about emotions associated with the drawn places. In Variation A, we employ a colour wheel to organise distinct types of emotions. Each of the six colours represents a specific category of emotions. The emotions legend is structured not hierarchically from top to bottom, but rather in a wheel format. To ensure clarity, the legend is limited to six emotions and corresponding colours (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Colour Wheel (Klaus, Germes, Guarascio 2022: 41)

Procedure Variation B: A Life Course

This variation has been developed to research on transitions in the life-course to develop a better understanding of domestic violence. The aim is to learn more about transitions as a temporal and material process and to grasp thick descriptions. In this way, the interview starts with a broader narration of the transition and zooms into the spatial and emotional dimensions.

- Step 1: Introduction

The first part of the interview compromises an introductory explanation of the interview and drawing. The interviewees are introduced to the research situation and the interest in their life course to learn more about the research topic. They can choose if they want to start to draw straight away or need to tell their story first and to draw later. For some interview partners the combination of narration and drawing can be very helpful, others might want to focus on the different aspects. It is helpful to start the interview with one stimulus such as, “I would like to ask you to tell me about your life story, not only about your experiences of violence, but about everything you can think of. I would also like to ask you to draw your story: on this page you may draw all the places of your life – where you went, where you lived, where you spent time.” Due to this open question the interview participants can choose what is important to them and how their story is told. - Step 2: The drawing

The second part of the interview focuses on stories and anecdotes that are related to space. If the interviewee has named or drawn a place, it can help to ask, “What was it like for you there? Would you like to tell me about your experience of this place? How can I imagine this place?” Sometimes places are drawn straight away and sometimes an important place appears by the reflection in the interview situation. It is helpful to see the map as a product of the interview situation. In this way there is, as is common in interviews, an ambivalence on how much time (and drawing) the researcher or the interview partner want to spend in one place. - Step 3: Emotions

The third part of the interview focuses on emotions. A range of colored pencils are offered. The interviewees can choose which colors they would like to use. It might be helpful to open like, “I would love to hear how you felt about the places you drew.” We can now use the colored pencils to record feelings in the places. The interviewees can freely express their feelings. This is to allow them to first reflect on what they felt and how this was expressed. In some cases, a color is enough to mark a feeling, in some cases body parts or the whole own body or even other people are drawn to show a feeling, in some cases symbols are chosen to represent a feeling. Sometimes it might be interesting to zoom into specific situations, using questions like: “What have you been feeling? How were you feeling in this place/situation/time?” The zooming in might be helpful as an interview technique to grasp thick descriptions.

Requirements

Various materials (see Suggested Tools) and ideally a quiet, undisturbed place to draw are important basic conditions. The interviews we conducted lasted between 25 minutes and three hours, depending on the topic, the interviewee’s condition, and time available.

Emotional Mapping interviews are carried out in a face-to-face setting, typically involving one researcher and one interviewee. On occasion, interviews have been conducted by a pair of individuals, with one assuming the role of the conversation leader while the other maintains a more observational and record-keeping role. The method does not fit digital formats because the materiality and the analogue process of drawing are fundamental to the method. Furthermore, talking about sensitive topics could possibly lead to retraumatization. Therefore, high ethical standards such as a support during breaks or after the interview are necessary.

Evaluation

Emotional Mapping is a qualitative interview method and therefore used in a scientific context. In our PhD projects, we use Emotional Mapping in order to conduct research with people who face vulnerability. Due to its roots in feminist epistemologies, Emotional Mapping proves particularly invaluable when researching sensitive personal topics, including but not limited to drug use, homelessness (Klaus et al. 2022; Germes & Klaus, 2021), domestic violence, and encounters with the police (Keitzel 2023; 2024).

We highly recommend approaching the interview situations by engaging participants with thorough preparation (especially regarding the necessary materials, see Suggested Tools), ample time, and a compassionate demeanour. Usually, the interviews occur in a one-to-one setting.

Additionally, we partly provide interviewees with an expense allowance as a token of appreciation for their participation.

The Emotional Mapping method was developed as a tool to enrichen the interview situation and to find other, creative ways to talk about lived experiences and living conditions that might be emotionally charged. The analysis of the map can be done differently. In our work we experimented with different solutions: We created collages in which we collected quotes of the interview transcripts and drawn maps (Klaus et al. 2022, p. 44ff). We combined qualitative content analysis (Kuckartz 2016) with situational analysis (Clarke 2011, see Keitzel, 2024). The analysis method can certainly become even more systematic, leaving room for improvement of e.g., standardization. And we are still in the search of space sensitive variants of Gounded Theory Methodology, which could fit the needs of qualitative, visual data analysis.

Example

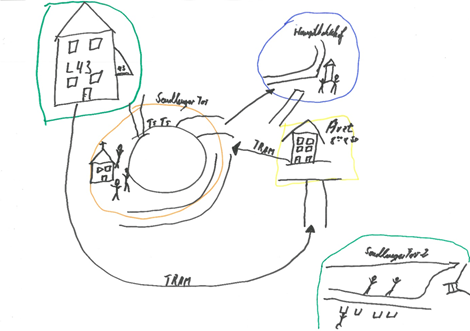

Figure 2: Emotional Map of a homeless person who uses drugs in Munich/Germany (Source: S. Keitzel, L. Klaus & S. Schäfer)

This map shows the everyday space and life of Andreas from Munich, Germany. Andreas frequents a drug help facility (L43) as part of his routine. He must visit the doctor daily to receive substitutive (?) medication. Notably, the map features a duplicated depiction of the “Sendlinger Tor” (centre left, bottom right) a gathering spot in Munich for marginalized people who use drugs.

Figure 3: Emotional Map of a Roma woman who had a racist experience with the police (Source: S. Keitzel, L. Klaus & S. Schäfer)

This map shows the everyday space and life of Romni from Frankfurt, Germany. She is a Roma woman working in social work. She regularly observes racist behavior toward her clients. In addition, she experienced racist treatment as a victim in a traffic accident at the “Post”. There, she used the colors purple, blue and red which stand for negative emotions like anger, sadness, and powerlessness.

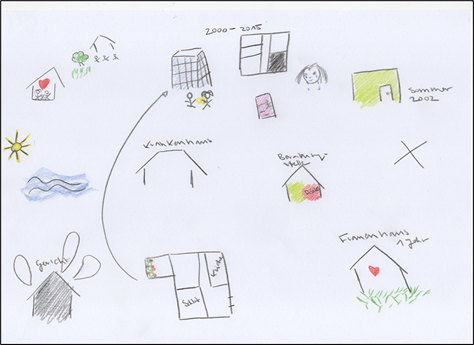

Figure 4: Example of an Emotional Map of the biography of a woman who experienced domestic violence (own compilation of drawings from multiple interviews) (Source: S. Keitzel, L. Klaus & S. Schäfer)

This map shows an example of how a map by a woman who experienced domestic violence might look. Usually, the interviewees draw their biography by showing single places where they have lived or single events they have experienced. Symbols like hearts or a crying face represent emotions they have felt. Colours like black, green, and red symbolize emotions such as sadness, hope and fear. Often representations of the space such as trees, weather elements or flowers are used to represent an atmosphere they have experienced.

Useful Ressources

- https://drogenalternativeplanung.wordpress.com/portfolio/emotionelle-kartierung-methode/

- Klaus, Luise; Germes, Mélina; Guarascio, Francesca (2022): Emotional Mapping und partizipatives Kartieren – ungehörte Stimmen sichtbar machen. In: Finn Dammann & Boris Michel (Ed.): Handbuch Kritisches Kartieren. Bielefeld: transcript (Sozial- und Kulturgeographie, 51), S. 37–53.

- Germes, Mélina; Klaus, Luise (2021): When marginalized subjects map their city: Counter-mapping experiments with drug users in some German and French neighborhoods. In: Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 152 (1), S. 96–124.

Suggested Tools

- White sheet of paper; preferably in a size of approx. 30 x 40 cm/ DinA 3

- 6 coloured felt pens (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, violet) or a box of coloured pencils

- 1 black felt pen

- Guideline for the interview

- Voice recorder

- Paper and pen to take notes

- For Variation A: Colour Wheel

References

Ahmed, Sara (2004): Affective Economies. In: Social Text 22 (2), S. 117–139. https://voidnetwork.gr/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Affective-economies-by-Ahmed-Sara-1.pdf

Campos-Delgado, Amalia (2018): Counter-mapping migration: irregular migrants’ stories through cognitive mapping. In: Mobilities 13 (4), S. 488–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2017.1421022

Clarke, Adele E. (2012): Situationsanalyse. Grounded Theory nach dem Postmodern Turn. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Downs, Roger M.; Stea, David (2011): Cognitive Maps and Spatial Behaviour: Process and Products. In: Martin Dodge, Rob Kitchin, Chris R. Perkins (Ed.): The map reader. Theories of mapping practice and cartographic representation. Chichester, West Sussex, Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, S. 312–317.

Germes, Mélina; Klaus, Luise (2021): When marginalized subjects map their city: Counter-mapping experiments with drug users in some German and French neighborhoods. In: Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin de Méthodologie Sociologique 152 (1), S. 96–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/07591063211040234

Gieseking, Jack Jen (2013): Where We Go From Here. In: Qualitative Inquiry 19 (9), S. 712–724. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800413500926

Haraway, Donna (1988): Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. In: Feminist Studies 14 (3), S. 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066

Keitzel, Svenja (2024): Folgenreiche Begegnungen mit der Polizei. Rassistische Verhältnisse raumtheoretisch untersucht. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot.

Keitzel, Svenja (2023): Geographien der Begegnung im Jugendclub: Perspektiven der Jugendsozialarbeit auf die Polizei. In: Hunold, Daniela; Brauer, Eva; Dangelmaier, Tamara (Ed.): Stadt. Raum. Institution. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, S. 173–189.

Klaus, Luise; Germes, Mélina; Guarascio, Francesca (2022): Emotional Mapping und partizipatives Kartieren – ungehörte Stimmen sichtbar machen. In: Finn Dammann & Boris Michel (Ed.): Handbuch Kritisches Kartieren. Bielefeld: transcript (Sozial- und Kulturgeographie, 51), S. 37–53.

Kuckartz, Udo (2016): Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. Methoden, Praxis, Computerunterstützung. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Laliberté, Nicole; Schurr, Carolin (2016): Introduction: The stickiness of emotions in the field: complicating feminist methodologies. In: Gender, Place & Culture 23 (1), S. 72–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.992117

Schurr, Carolin; Strüver, Anke (2016): „The Rest“: Geographien des Alltäglichen zwischen Affekt, Emotion und Repräsentation. In: Geogr. Helv. 71 (2), S. 87–97. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-71-87-2016

Leave a Reply