Visual and textual narratives on fieldwork

Author:

Nora Mariella Küttel

Citation:

Küttel, N. M. (2024): Photography and Autoethnography. Visual and textual narratives on fieldwork. In: VisQual Methodbox, URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2023/11/25/photography-and-autoethnography/

Essentials

- Autoethnographic photo-essay as reflexive method: The autoethnographic photo-essay is a method to merge field photographs with post-fieldwork reflections, offering a personalized approach for exploring the researcher’s positionality and documenting field experiences visually and textually.

- Incorporation of sociological introspection and emotional recall: The practices of systematic sociological introspection and emotional recall, inspired by Carolyn Ellis, are integral components of the photo-essay. These techniques allow the researcher to actively recall thoughts and feelings by revisiting the emotional and sensory aspects of captured moments, contributing to a more profound reflection on the field experiences.

- Autoethnography and the interplay of text and image: The autoethnographic photo-essay is an attempt at a more active incorporation of visual materials in autoethnographies, recognising the evocative potential of photographs not only for the researchers but also for the readers. Additionally, it should be seen as an encouragement for experimenting in the acquisition, analysis, and communication of knowledges and an invitation to challenge traditional disciplinary boundaries.

Description

The autoethnographic photo-essay is an approach to bring together photographs taken by the researcher in the field and post-fieldwork reflections. Since this is not an established or fixed method or medium, I will discuss it through my lens and explain my way of finding and applying it.

I discovered this method during my PhD research where I spent several months in Detroit, researching the interrelations of artistic practices and urban space. While in the field, I took numerous photographs – not only of artworks or other research-related scenes but also of seemingly irrelevant things. Browsing through them at a later point, I discovered that many of them acted as memory anchors as well as stimuli for emotions. Exploring this further, I added written narratives to selected photographs. These texts articulate the observations and interpretations of the depicted scene, encapsulating my thoughts and emotions associated with it.

This practice is informed by Carolyn Ellis’ methods of systematic sociological introspection and emotional recall (Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p. 167; Ellis, 1991). Systematic sociological introspection encompasses “… actively recalling thoughts and feelings from a social standpoint. Introspection emerges in and represents social interaction and occurs in response to bodily sensations, mental processes, and external stimuli, while it affects these same processes” (Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p. 167f.). Further, emotional recall means imagining “… being back in the scene emotionally and physically. Revisiting the scene in that way leads to recalling other details, which produces deeper emotional remembering” (Bochner & Ellis, 2016, p. 167). Sociological introspection and emotional recall allowed me to revisit the scene and the moment of capturing the photograph as well as lead to further associations concerning the subject of the photograph, facilitating the recall of my emotions and sensations.

The approach is embedded in the larger field of autoethnography which, according to Reed-Danahay (2017, p. 145), “… is an umbrella term that can refer to autobiographical narratives about the doing of ethnography or being an ethnographer, to the work of an anthropologist doing ethnography in their own society …, and to genres of fiction and memoir …”. Hence, autoethnography is usually written in the first-person narrative and aims at bringing the researcher’s experiences and emotions to the fore. It is a “… substantial shift from writing about others to writing about one’s self” (Küttel, 2021, p. 58), as the addition of auto to ethnography implies. However, autoethnographies are not solely about the autoethnographer, they also place “… the self within a social context” (Reed-Danahay, 1997, p. 9). This relational aspect is of particular interest here as the autoethnographic photo-essay aims at gaining deeper and broader knowledges of the relations with research participants as well as the social context of the field through the researcher’s introspection and reflection (Butz, 2010, p. 138f.).

Autoethnography is usually in a written form and includes diverse forms and styles such as dialogs, poems, and short stories, interweaving “…emotion, embodiment, spirituality, and self-consciousness … as relational and institutional stories [with] history, social structure, and culture …” (Ellis & Bochner, 2000, p. 739). Since recalling and introspection can be based on field notes and one’s memory as well as visual material, I suggest incorporating these materials in the (published) autoethnography more actively and not only using them as a starting point for reflection. Not least, the photographs can act as evocative mediums for the reader, too, provoking critical reflections and creating relations between researcher, reader, and research topic (Küttel, 2021, p. 59). However, the autoethnographer should be mindful of their vulnerability when sharing personal and intimate thoughts and experiences as it might lead to stigmatization and prejudices (Küttel, 2021, p. 59).

What should be kept in mind is that once photographs are published, the author also gives away control over their reception. That others might look at them in their own ways and interpret them differently than intended must be acknowledged – however, does this not also apply to written forms of knowledge production? Also, the social conditions and effects that a photograph might reproduce need to be considered, and ethical and legal issues (e.g., who/what is depicted/described) connected to the photo as well as the accompanying text should be taken into consideration before publication.

Finally, the relationship between photographs and written word is of particular interest here. Their specific interaction as part of the photo-essay can be described through Roland Barthes’ concept of relay which describes a complementary relationship of text and image where both “… are fragments of a more general syntagm and the unity of the message is realized at a higher level, that of the story, the anecdote, the diegesis” (Barthes, 1987, p. 41). In the book “Doing Visual Ethnography”, Sarah Pink argues that “[p]hotographs can be used to create representations that express experiences and ideas in ways written word cannot. This is not to say that one medium is superior to the other, but to seek the most appropriate way to represent different aspects of ethnographic experience and theoretical and critical ideas” (Pink, 2007, p. 163). This includes the observation that also the written word possesses the ability to portray and express concepts in ways that photographs cannot. Embracing this perspective opens the door to experimenting with various approaches to acquiring, analysing, and documenting knowledges. This approach challenges traditional boundaries in disciplines and genres, fostering a capacity for thinking beyond conventional constraints and encouraging more creative, reflexive, and critical approaches to both ethnography and autoethnography.

Procedure

Since I regard doing research as a situated and personal but also experimental and dynamic practice, the following steps should only be regarded as suggestions for how one could proceed. But I would rather suggest that you, as a researcher, try to find out your way of creating auto-ethnographic photo-essays. So, please take the following as neither more nor less than some proposals and stimuli.

(I would like to point out here that, thinking with Katz (1994) and Nast (1994), I conceive field as a dynamic and situational social and physical space that is constructed by the researcher for the purpose of research. It is also “… an intermediate space, situated between what is (supposed to be) known and unknown, between being an outsider and an insider, and between home and away” (Küttel, 2021, p. 61). The field as well as fieldwork is thus shaped by politics, power relations, and emotions.)

- Step 1: Take your photos! While in the field, take photos of things that spark your interest, of situations that feel important and of those that feel mundane, and of moments when you think ‘This – for whatever reason – should be part of my research diary’, but you don’t have that diary at hand right now.

- Step 2: Take your time! With some distance (spatial, temporal, emotional), take your time to look through the photographs and assort those that you would like to use for systematic sociological introspection and emotional recall.

- Step 3: Take your time, again! Go through the photos one by one. Take your time looking at them, revisit the scene and the moment of taking the photograph, and allow the process of emotional remembering. You can also follow further associations that are evocated by the photograph.

- Step 4: Take your pen (or computer)! Write down what you discovered, recalled, and sensed through the introspection. Write everything down that comes to your mind, this does not need to be a particularly beautiful or systematic text, you can polish and review it later on – if you wish. Now that you have combined photographs and written word, you can revisit both to reflect on their broader meaning for your research (or yourself).

Requirements

- a researcher doing fieldwork

- a camera or smartphone

- time for post-fieldwork reflections using systematic sociological introspection and emotional recall

Example

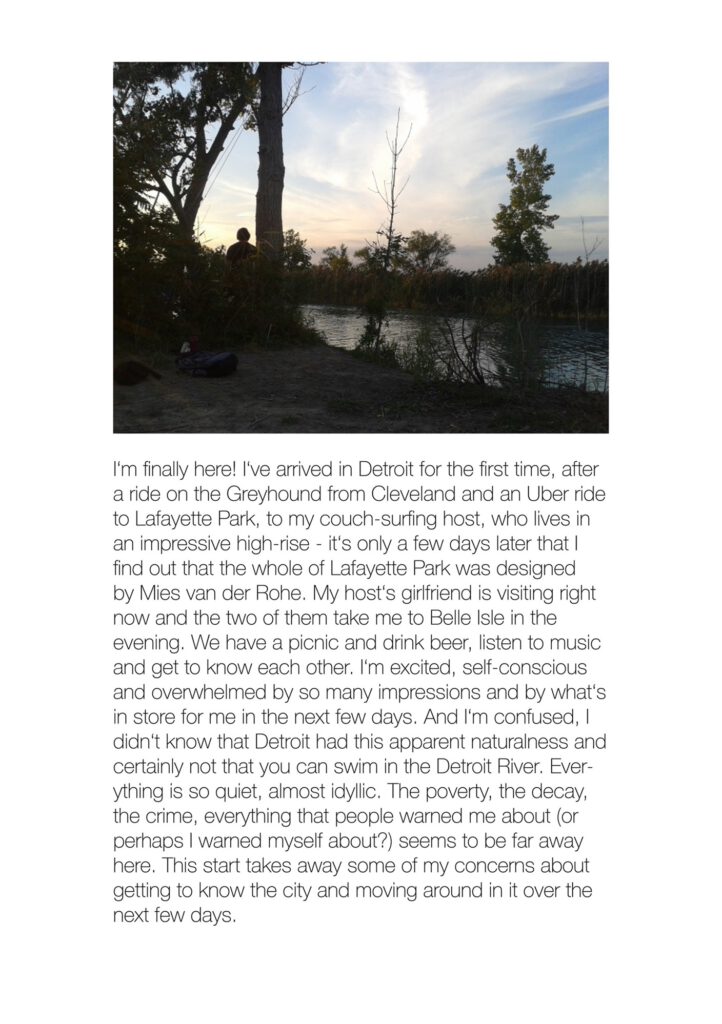

In the following, I will introduce an example from the photo-essay I created after my first research stay in Detroit in 2016. While I have written about the photo-essay and have shown extracts from it before (Küttel, 2021, 2022, p. 67ff.), the following extract (as well as the essay as a whole) has never been published. For the extract, I used a photograph that I have not taken to create a photo-essay but that was just a mundane documentation of my first-ever day in Detroit.

(Source: N.M. Küttel)

The extract encompasses two primary themes. Firstly, the text delves into the impact that narratives surrounding Detroit had on me. It can be read as my coming to terms with the stereotypes, images, and narratives about the city, realising how they influenced my sense of place, and it gives a first hint at how it changed while being there – after spending time in the city, I developed a more nuanced view on the urban setting and developed a sense of place that allowed me to navigate the city better. It also helped me to deconstruct the many harmful, racist, and classist narratives about the city. Secondly, and this directly ties in with that, this underscores the importance of field-based research, enabling a deeper and more comprehensive understanding of a place. It also raises questions about the methodology of entering a field and navigating its inherent complexities (Hyndman, 2001, p. 265), emphasizing the researcher’s role as an outsider. It also contemplates the preparation required for fieldwork, drawing on the notion of the researcher as a ‘stranger’ (Katz, 1994, p. 68) and addressing the uncertainties associated with the initial stages of exploration (Küttel, 2022, p. 69f.). With all this in mind, “I regard the photo-essay as both a method to approach my positionality as far and as well as possible, and as a visual and textual product capturing field-experiences” (Küttel, 2022, p. 70). It supported me in gaining “… deeper access to how my perspective in the field is constituted and eventually, where my knowledge is positioned and situated. Thus, this inward and outward look allows critical reflexion on research processes and methods as well as questions of power and responsibility” (Küttel, 2021, p. 63).

Consequently, the photograph serves a dual purpose: it acts as a catalyst for emotional recollection and as a representation and reconstruction of the scene, both visually and emotionally (Rose, 2014, p. 28). This concept is grounded in my conceptualization of the field as a dynamic and situational space of in-betweenness. The photographs are taken in the field, and the written narratives are added later, not only blurring the binary distinction between field and non-field but also emphasizing the intimate and personal nature of fieldwork. As researchers traverse between spaces, their “… intellectual, sociocultural, and economic baggage” (Hyndman, 2001, p. 265) accompanies them.

Suggested Tools

- camera or smartphone

- a photo editing software that can combine visual data and text (word, illustrator, etc.)

- if you want to go analogue: printed photos, paper, and a pen

References

Barthes, R. (1987). Image, music, text (S. Heath, Trans.). Fontana Press.

Bochner, A. P., & Ellis, C. (2016). Evocative autoethnography: Writing lives and telling stories. Left Coast Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315545417

Butz, D. (2010). Autoethnography as Sensibility. In D. DeLyser (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Geography (pp. 138–155). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857021090

Ellis, C. (1991). Sociological Introspection and Emotional Experience. Symbolic Interaction, 14(1), 23–50. https://doi.org/10.1525/si.1991.14.1.23

Ellis, C., & Bochner, A. P. (2000). Autoethnography, Personal Narrative, Reflexivity: Researcher as Subject. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (2nd ed, pp. 733–768). SAGE.

Hyndman, J. (2001). The field as here and now, not there and then. The Geographical Review, 91(1–2), 262–272. https://doi.org/10.2307/3250827

Katz, C. (1994). Playing the Field: Questions of Fieldwork in Geography. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 67–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00067.x

Küttel, N. M. (2021). Autoethnography and Photo-Essay. Combining written word and photographs. In J. Wintzer & R. Kogler (Eds.), Raum und Bild—Strategien zur qualitativen Datenanalyse (pp. 57–67). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-61965-0_5

Küttel, N. M. (2022). When art and space meet. An ethnographic approach to artistic practices and urban space in Detroit. Franz Steiner Verlag.

Nast, H. J. (1994). Women in the Field: Critical Feminist Methodologies and Theoretical Perspectives. The Professional Geographer, 46(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0033-0124.1994.00054.x

Pink, S. (2007). Doing visual ethnography: Images, media and representation in research (2nd ed). SAGE. https://doi.org/10.4135/9780857025029

Reed-Danahay, D. (1997). Introduction. In D. Reed-Danahay (Ed.), Auto/ethnography: Rewriting the self and the social (pp. 1–17). Berg.

Reed-Danahay, D. (2017). Bourdieu and Critical Autoethnography: Implications for Research, Writing, and Teaching. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(1), 144–154. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v19i1.1368

Rose, G. (2014). On the Relation between ‘Visual Research Methods’ and Contemporary Visual Culture. The Sociological Review, 62(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-954X.12109

Leave a Reply