A critical multi-temporal comparative cartography to visualize colonial inscriptions in urban infrastructures

Author:

Schmalen, Nelo

Citation:

Schmalen, N. (2024): Mapping Coloniality. A critical multi-temporal comparative cartography to visualize colonial inscriptions in urban infrastructures. In: VisQual Methodbox, URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2025/03/03/mapping-coloniality/

Essentials

- Usefulness: Mapping colonial inscriptions renders physical structures of the colonial past visible and locates them in current urban infrastructures.

- Focus: Locating colonial structures in contemporary urban infrastructures.

- Postcolonial approach: Mapping coloniality critically re-reads and visually retraces historical sources and connects them spatially and with current knowledge.

- Approach: Mapping coloniality uses mixed methods with a focus on the urban area of interest, consisting of comparing maps from different periods, finding textual information in them and analysing historical photographs, as well as reading historical texts for information on the urban development of the area and the wider context.

Description

Mapping Coloniality aims to link local, historical and spatial changes with larger (pre-/post-/colonial) entanglements and contexts of exploitation. It is a way of doing visual postcolonial analysis by using maps and archival sources. It goes beyond the analysis of isolated colonial structures such as monuments or single buildings and, instead, focuses on contemporary urban infrastructures and the colonial heritage inscribed within them. With the coloniality (Quijano 2000, Ha 2017) of the urban, I describe the fact that contemporary infrastructures are shaped by colonial infrastructures, that is, infrastructures (land, roads, waterways, buildings, landscapes) that were built during and by means of the profits of exploitation in an unequal colonial system. They were sometimes overwritten, yet often shaped subsequent urban transformations. This method allows us to understand and visualize these infrastructural changes of, for example, post-colonial European port cities as part of a long process of colonial wealth accumulation and distribution that has massively shaped their urban infrastructures.

This historical-geographical method is also postcolonial, as it is informed by a critique of power and domination. This is especially important since some of the maps used were created in colonial contexts and times. The method complements existing critiques of classical cartography with regard to its positionality and particularity (Dammann/Michel 2022). This is achieved by embedding local changes of the mapped area in the context of global history and thus linking them beyond their local historical and nation-state context. In effect, this dissolves the particularity of the map section and undermines the unnamed positionality criticised by Haraway as a “view from nowhere” (Haraway 1988).

Methodologically, cities are analysed in historical, geographical or urban research, but less often with a qualitative research focus on the coloniality of urban infrastructures. In parallel, and because of digitisation, archival resources are increasingly available in digitised archives. Some offer the possibility of overlaying a digitised historical map with a contemporary map of the existing urban structures (e.g. Amsterdam City Archive). However, there are few comparative cartographic map analyses that make colonial infrastructures visible by visualising the changes in material infrastructures (e.g. the coastline) and linking the current infrastructure to its history in space-time.

The added value of this method lies in the fact that it establishes a connection between historical studies and geography by critically reviewing and informing historical knowledge on the basis of historical maps and sources, and then linking this to current knowledge, and finally spatially localising it in today’s physical structures.

Mapping Coloniality consists of an iterative approach of analysing material from different sources:

- a comparative map analysis combined with

- archival documents, secondary texts and image analysis; and

- doing “eye work” (Schlögel 2003) by reading the city through walking and closely observing the current urban infrastructures, and then documenting the traces found through photography

- linking local changes to global history.

Visual material using this method was first produced as part of my Master’s thesis. It was published as an open access working paper in 2023, including a new introduction. The publication also aimed to make the new knowledge about the colonial infrastructures of Flensburg accessible to the local discourse on (post)colonial memory. In this way, the maps in particular function not only as the results of analysis, but also as a tool for knowledge transfer. In addition, the newly created lines of Flensburg’s shoreline became part of a cooperation with the artist Felisha Maria Carénage (Wörner et. al. 2024), who does art research on this topic. In the piece Gléve from her project Elegies: Postcolonial Postcards, she combines her own research on the legacy of Caribbean boat-building with the shorelines of Flensburg as part of an exploration of the port city’s infrastructure and culture of memory.

Limitations

Four limitations shall be mentioned here:

- From a social science point of view, this method is technically quite demanding, as software for processing and creating georeferenced maps must be known or learned. In addition, appropriate hardware (RAM and large/second screen) is required to work comfortably on the map. This also limits its participatory use.

- This method does not claim to be participatory. This is due to the high technical requirements and the high level of scientific analysis required to generate new knowledge/contextualisation. However, once this has been elaborated, there is the possibility that the material produced can be further processed (potentially participatory) or, as in this case, incorporated as knowledge by other actors in the arts or in urban planning.

- The coloniality of cartography: Given the colonial history of cartography and the close connection of this method to dominant systems of knowledge production, it is important to reflect on the implications of e.g. power structures in knowledge production and how the knowledge produced can be made accessible.

- Open access & copyright: When making the new maps accessible, it is advisable to pay close attention to copyright and understand its implications. Open source software can be used as a tool. Current maps are increasingly available as open data from freely available public databases under the European Data Act. Nonetheless, raw data may require processing, and the specific copyright needs to be respected. When selecting historical maps and photographs, one has to consider their age (usually 70 years old or more, depending on specific item), whether they are free to use (by citing the source) or whether a licence for their use may be required. This is particulary important because they will be used to create a new map, which consists of traced overlays. One´s own photographs can be used instead of archive photographs that require licensing. The photographs and newly created maps can then be made available under the Creative Commons Licence (e.g. CC BY-SA 4.0) with appropriate referencing of the resources.

Procedure

This method consists of an iterative process of mixed methods: Firstly, comparative cartography is used (A). Next, archival documents, secondary texts and images are analysed (B). Then, the city is walked through and read, with traces documented through photographs (C). Finally, the tracings are combined in one map (D).

(A) Preparing a comparative multi-temporal cartography

- (a1) Think about an area of interest and possible periods/phases/important local and global events that have had an impact on this area (e.g. port infrastructure of a city that has been the nexus of economic flows and the accumulation of colonial profits from enslaved labour or enslavement).

- (a2) Obtain a current map of the area of interest and its surroundings, ideally a geo-referenced vector data map.

- (a3) Search archives for historical city maps showing the area of interest at a sufficiently detailed scale and for the relevant periods. If they are not digitized, find the original maps and have them scanned at a good resolution in the archive.

- (a4) Produce a Geographic Information System (GIS) and geo-reference the current map.

- (a5) Orient the historic maps north and trim them to the area of interest. If necessary, reduce the data (pixels per inch) to a necessary level to optimize software performance. Depending on the features of the software, you may need to use a separate image-processing program to do both.

- (a6) Upload the historic maps to the GIS and transform each to the grid of the geo-referenced map by selecting reference points of structures that exist in both maps. Try to minimise discrepancies through the choice of reference points.

- (a7) Compare the maps and look for major and gradual changes in the infrastructure. Try to narrow down the extent and time period of these changes.

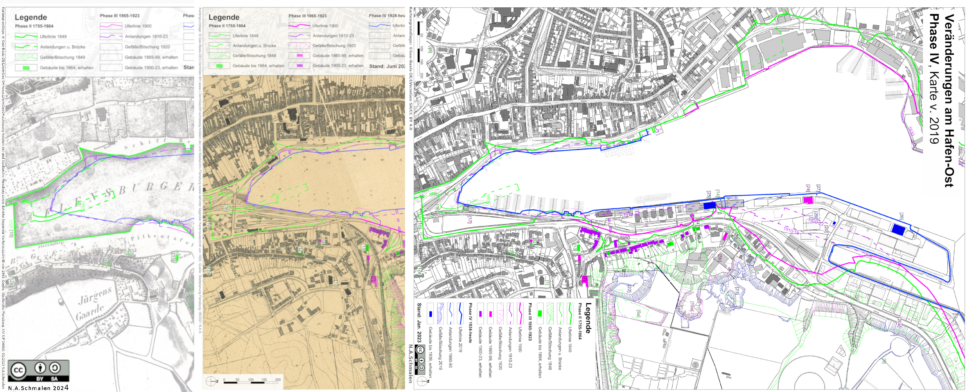

Image 1: Comparative cartography of Flensburg Eastern Port, each colour line stands for the shoreline of a time zone (Copyright “CC BY-SA 4.0”)

(B) Analysis of archival documents, secondary texts, and historical images.

- (b1) Research local archives, historical documents and photographs that are likely to represent parts of the area of interest.

- (b2) Locate existing historic buildings on the maps and mark them in the GIS according to the established time phases.

- (b3) Analyse textual descriptions from (primary and secondary) literature (e.g. on shore landings, terrain erosion, construction/demolition of prominent buildings and mobility infrastructure) to identify localized knowledge and plot it on the GIS in accordance with the time phases.

- (b4) Acquire knowledge of global history and the histories with which the local place is connected. Consider how local urban transformations are embedded in global history (e.g. changes in exploitation (enslavement) or mobility (fossil fuels)). Identify local changes and link them to global changes to identify periods of transition in local urban structures.

(C) Reading the city and documenting traces via photographs.

- (c1) Walk carefully through the area of interest, observing the landscape, waterways, coastline, buildings, and mobility infrastructure. As you gain knowledge of historical infrastructures, look for traces, overlays, or replacements of old infrastructures. How does the newer infrastructure relate to the old one in terms of structure, design, and naming? For instance, do newer buildings reference colonial infrastructures? How does the present course of streets correspond to former infrastructures?

- (c2) Photograph current traces of historical infrastructures and geo-reference (locate) the photos on the map.

(D) Finally, combine your tracings of infrastructures from different historical maps and the contemporary map. Produce one or more maps to show the progress and currently existing colonial infrastructures. Combine the map with current and archival photographs of important findings. Be aware that textual additions will help viewers understand the context of changes and their simultaneous embeddedness in local and global contexts.

- (d1) Based on the identification of ruptures in Step (B), the maps and findings from A- C are structured, and phases of local urban transformations are identified.

- (d2) Each period/phase should be drawn in a separate colour, including the shoreline/ landmasses, buildings, mobility infrastructure, geomorphology/slopes, and add a legend for the developed time phases. This should be repeated as more knowledge is gained from (B) and (C).

Requirements

- Necessary software features: software to create a Geographic Information System (GIS) with which to draw vector graphics in a geo-referenced space. Ideally, this software should be both free and open source (e.g. QGis). Graphics editing software with sufficient functionality is also available as free and open source software (e.g. Gimp). Printing facilities for colour printing, ideally for A3 or larger formats.

- Access to local archives with texts, maps, and photographs.

- Physical access to the districts of interest.

Evaluation

- The method can be applied in any context concerned with reading and analysing existing urban infrastructures and their transformations in time and space, especially when there are forgotten, repressed, entangled, or divided histories (Randeria 1999) of a place or infrastructures that are to be rendered visible.

- It is a time intensive method, as it involves several steps and mixed methods and iterative work cycles. Additionally, it takes time and resources to learn the software and the technical resources like data storage, and a PC equipped to process the data is necessary.

- Costs may accrue for hardware and for software, they can be avoided by using open-source software. Travel costs might occur for travelling the area of interest.

Example of colonial materiality of Flensburg / North Germany

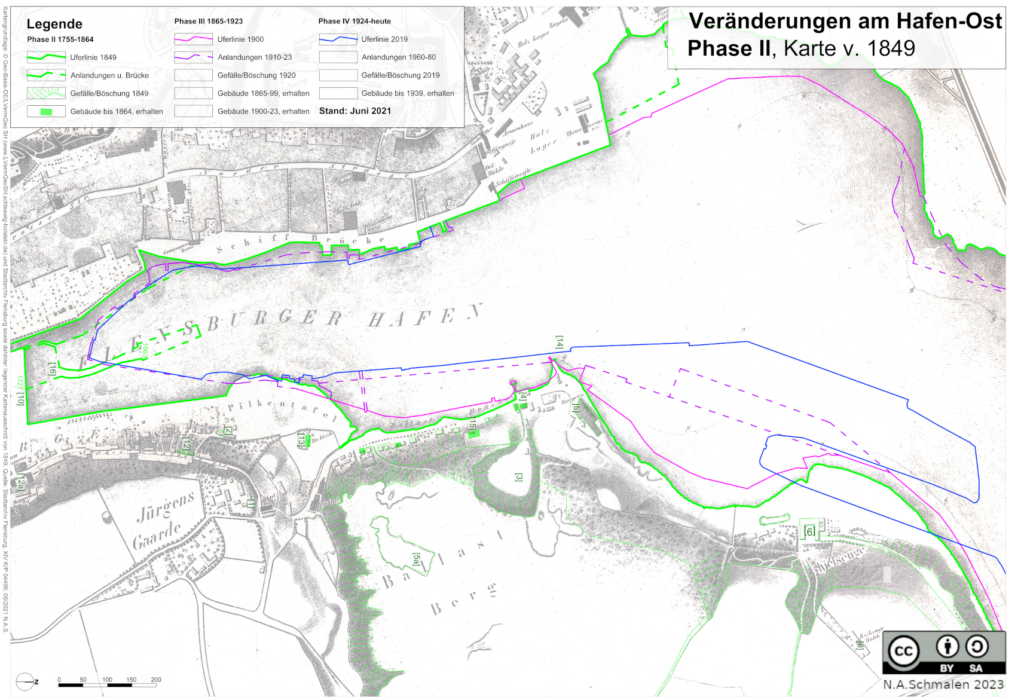

Image 2: Results of the comparative cartography of Flensburg Eastern Port with maps from three transformation-phases (Copyright “CC BY-SA 4.0”)

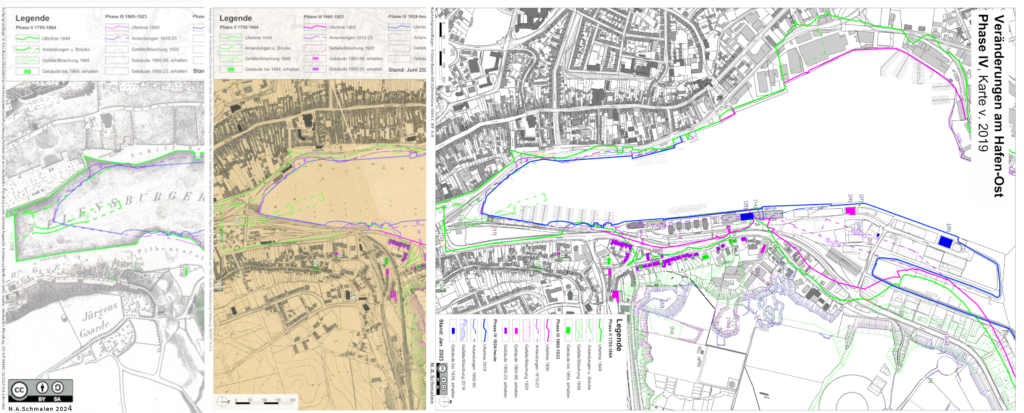

Image 3: Colonial materiality – the excavation of sand for bricks as ballast in sailing-ships to the Caribbean, can still be read in the morphology of today’s urban landscape. (Copyright “CC BY-SA 4.0”)

Based on the research question “What is the coloniality in the (material) structures of Flensburg’s Eastern Port?” and the lack of available methods to analyse coloniality in urban infrastructures, this visual qualitative method was developed as part of my master’s thesis. Starting from two theoretical approaches, the analysis first ascertains how the place of interest is part of an ‘entanglement history’ (Conrad/Randeria 2013) that connects the local with the global; and secondly, how coloniality (Quijano 2000/Ha 2017) is embedded in the urban transformations and inscribed in contemporary material structures. The analysis illustrates how more than 300 years of colonial history are inscribed in the materiality of Flensburg’s Eastern Port. These material traces are structural; they can be seen in the shoreline, the morphology of the terrain, the buildings, and the (traces of) mobility infrastructures that. Consequently, coloniality still characterises the settlement structure today and continues to shape what is currently imagined for the future transformation of the industrial port area to a waterfront development. Through the map works, in combination with the photographs, it is spatio-temporally located and made visible (Schmalen 2023: iii, 18, 133).

The example in Image 3 shows how the terrain was shaped by the excavation of sand for ballast and by landing material to extend the shore area (marked with [3] in the map section). The sand was used to make bricks for ballast in sailing ships, to make them seaworthy for crossing the Atlantic. In the Caribbean (e.g. in Charlotte Amalie on the island of St. Thomas), they were used as building material and still form part of the old town’s infrastructures. Furthermore, the path to the former place of sand excavation (former “Ballastberg”) is now part of the settlement infrastructure whose shoreline has changed massively. This path is still marked by the historic building from 1744, at its crossing with the former shoreline. The former shoreline became a mobility area first for the railway lines and then for the main road. The layering of different usages in one area, and how one has informed the other, becomes visible and readable through the multi-temporal and multi-modal map work.

The interdisciplinary method presented here thus enables a structural analysis of the continuing effects of colonialism in the materiality of the city. It also shows how qualitative geography can work visually and multi-scalarly at the interface of postcolonial studies, transformation studies and urban research. Most importantly, this is a method dedicated to provide a multi-method analysis of urban infrastructures and how they are shaped by colonialism in order to create and make comprehensible knowledge about such structures and histories accessible to a broad audience.

Suggested tools

- Software: A free and open-source software for creating a geographic information system (e.g. QGis), image editing software for graphics (e.g. Gimp)

- Possible data sources: Openly available geobasis data (Open GBD) from the surveying and geoinformation departments of state/municipal/city authorities, city archives for historical maps, texts and photographs from archives and historical research.

- Tools: pens and transparent paper for preliminary hand drawings, camera, printed maps for area walking.

References

Conrad, Sebastian/Randeria, Shalini (2013 [2002]): Einleitung: Geteilte Geschichten- Europa in einer postkolonialen Welt. In: Conrad, Sebastian/Randeria, Shalini/Römhild, Regina (Hg.): Jenseits des Eurozentrismus:. Postkoloniale Perspektiven in den Geschichts- und Kulturwissenschaften. Frankfurt am Main, New York, 32–70.

Dammann, Finn/Michel, Boris (Hg.) (2022): Handbuch Kritisches Kartieren. Bielefeld. https://elibrary.utb.de/doi/book/10.5555/9783839459584

Ha, Noa K. (2017): Zur Kolonialität des Städtischen. In: Zwischenraum Kollektiv (Hg.): Decolonize the City! Zur Kolonialität der Stadt – Gespräche, Aushandlungen, Perspektiven. Münster, 75–87.

Haraway, Donna(1988): Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective. In: Feminist Studies. Vol. 14, No. 3 (Autumn, 1988), 575-599.

Schmalen, Nelo A. (2023): Kolonialität der urbanen Transformationen am Hafen-Ost in Flensburg. Untersuchung zum Umgang mit kolonialen Strukturen im Rahmen der Konversion eines innerstädtischen Hafengebietes. In: Politische Ökologie – Working Paper Reihe, AG Integrative Geographie, Europa-Universität Flensburg, Flensburg.

https://www.uni-flensburg.de/fileadmin/content/abteilungen/geographie/poe-euf/2023-wp1-schmalen.pdf

Schlögel, Karl (2004): Im Raume lesen wir die Zeit. Über Zivilisationsgeschichte und Geopolitik. München.

Quijano, Aníbal (2000): Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism and Latin America. In: Nepantla: Views from South. 1 (3), 533–580.

Randeria, Shalini (1999): Geteilte Geschichte und verwobene Moderne. In: Rüsen, Jörn/Leitgeb, Hanna/Jegelka, Norbert (Hg.): Zukunftsentwürfe. Ideen für eine Kultur der Veränderung. Frankfurt/Main, New York, 87–96.

Wörner, Lara/Schmalen, Nelo/Carstensen-Egwuom, Inken(2024): Flensburger Uferlinien.

https://flensburg-postkolonial.de/en/flensburgs-shorelines/