Author:

Jana Wieser

Citation:

Wieser, J. (2024): Multidimensional and embodied mapping. In: VisQual Methodbox, https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2024/04/17/multidimensional-and-embodied-mapping/

Essentials

- Background: In qualitative social research, visual and linguistic forms of expression and perception are usually given priority. However, in order to analyze and understand power dynamics more broadly, it is important to consider the interplay of different forms of sensory expression and perception.

- Aim: To present forms of perception and expression of different sensual modes as well as their interplay and communication in an embodied and multidimensional mapping, as a rhizomatic process.

- Benefit: To understand power relations more comprehensively.

Description

Current cartography and maps are preceded by an extensive history of their importance in underpinning dominant power structures, oppression, and ignorance (see e.g. Dodge & Perkins 2008). At the same time, maps offer the possibility to present elements in (previously invisible) compositions and relationships to each other and thus to uncover new aspects (cf. Clarke 2012; Ruck & Mannion 2020). For instance, deeply inscribed social structures, dynamics and categories can be reflected, criticized, and analyzed with regard to dominant hierarchical and exclusionary (e.g. imperial and patriarchal) power dynamics (cf. Clarke 2012). This also ties in with the idea of a ‚multidimensional and embodied mapping‘. This approach aims to understand mapping as a multisensory process of mapping-as-doing, as becoming-a-map. Thus, it represents an attempt to view mapping itself as a structure, as a rhizome (cf. Deleuze & Guattari 1987; also Rieger et al 2022; Rieger 2016). As such, the aim is to illuminate and include different relationships between human and more-than-human aspects as well as actors and thus to understand intermediate power structures in particular.

In order to trace said power structures and their relations, an analytical focus on „emotional impulses” (Meißner 2019, p.127, own translation) as „embodied thoughts” (Rosaldo 1984, p.143), which implicate an entanglement of feeling and thinking, could be fruitful. It is precisely this interweaving that Meißner (2019) sees as particularly important and responsible for relating social segregation and exclusion on the one hand and understanding it on the other. Meißner (2019) attributes a certain ‘stickiness’ to emotions (she borrows the term and understanding from Ahmed 2013). Accordingly, connections to certain memories or places are difficult to dissolve and serve as connecting elements. Carrying this understanding forward, I consider it valuable to include more-than-representational and emotional aspects in mapping processes to let participants express and represent themselves in the process of participating in the mapping, thus entering into a reciprocal relationship for following power structures more comprehensively.

(More than) Human relations, connections, and encounters, as for instance between humans and animals, humans and plants or, as elaborated further down in an example, between humans and body parts, develop through embodied, relational and multisensory expressed aspects. Thereby, the resulting data (e.g. sketches, textures, pictures, soundscapes, videos…) is not limited to one-dimensional or fixed (sensory) expressions and perceptions experiences or have to be translated into them accordingly.

However, this can often be observed in the context of linguistic or visual aspects: multisensory experiences as smells, textures, movements, or sounds are reduced to or translated into linguistic or visual aspects, which inscribes existing hierarchical social orders by prioritizing these aspects and stands in contradiction with ‘embodied thoughts’ and ‘emotional impulses’ (cf. Misharina & Bett 2023; Rieger et al 2022). Likewise, Braidotti (2014) sees a prioritization of language as insufficient, as a deepening inscription of a human- and eurocentric perspective and associated power structures. She emphasizes expression and cartography as relational. Thereby, she makes the argument to focus on the „relations between the relations“ (Braidotti & Fuller 2019, p.11) and to trace how relations are negotiated and produced, and how a transformation, a communication between the relationships, arises and is expressed. According to Braidotti, cartographies represent conglomerates, interplays of documents, networks and relationships, forming a network of „embodied signposts“ (Braidotti 2021, p.104). Following this, multidimensional and embodied mapping offers an opportunity to bring multimodal data and consequently multisensory modes of representation and expression into exchange with each other, and thus connect with each other on different dimensions. Movements and touches, smells, tastes, and sounds become thereby important ways of being and forming the assemblage (cf. Renold & Mellor 2013). This should contribute to a more extensive view of lines, spaces and modes of inclusion and exclusion, shaped by power dynamics. By revealing information about multimodal relationships and connections, multidimensional and embodied mapping makes visible points, lines, and spaces that would remain invisible if focusing on one-dimensional aspects and their relationships, or that would be suppressed by translating multisensory data into language (cf. Rieger et al 2022; Renold & Mellor 2013).

Multidimensional and embodied mapping represents a dynamic and open process that focuses on the ‘becoming’ of the map rather than aiming for a ‘result’, a map that emerges from the process (cf. Braidotti 2014; Deleuze & Guattari 1987; Rieger et al 2022). To prevent the continued unnoticed and ongoing inscription of hegemonic power relations, it is important to constantly question and (re)interpret the data, the maps, and the process of mapping (Kollektiv Orangotango+ 2018; Perkins 2017; Sletto 2009). This reflection should become part of the mapping process through the recording of memos, the writing of short notes or the exchange with others.

The mapping is embodied, as it represents the embodied multisensory expressions of the object of analysis (whereby object is not to be understood here as the opposite of subject, but as relational and dynamic). Thereby, bodies and minds, expressions, and perceptions are entangling, which rejects a dualist notion of separation (cf. Longhurst 1997). This embodiment influences at the same time the perception of the object of analysis in its dynamic and relational understanding. Thus, embodiment is, through its relations, always forming the perception of the object of analysis and in reverse, the experience and the perception are always to be understood as embodied (cf. Rieger 2023). The mapping process and the embodiment thus co-construct each other in a creative interplay (cf. Rieger 2023; Braidotti 2014).

Given the multimodal nature of multisensory data, the corresponding mapping should be multidimensional. Since two-dimensional representations, such as lines on a piece of paper, may appear too solid, too immobile, the idea of multidimensional and embodied mapping is that the spaces, lines and points that represent the connections and relations within the assemblage can themselves also be experienced multisensorically. Thus, they can be represented in multiple dimensions in that they may, for instance, embody a texture and a movement inviting us to touch and play with them (cf. also Rieger et al 2022; Rieger 2016). Assembled from different materialities as for example fabrics, threads, and cords that can be (physically) perceived through different senses and at the same time embody different forms of expression, various dimensions of expression and perception are interwoven and entangled for the analysis. The multidimensionality and embodiment of sensory experiences and perceptions are thus reflected in the process of mapping as database and analytical method.

Procedure

- Familiarizing oneself with the subject matter and its embodiment: How are different senses related to the subject? How do they interact? Try to quietly explore different senses, preferably with eyes closed, as language/linguistic and visual aspects are usually prioritized.

- Start mapping by representing different sensory perceptions/ experiences/ modes of expression using different materials. Consider their processing (texture, color, size, lettering, images, …) and their connections and relationships in association with the situation: How can thoughts/ feelings/ sounds/ images and depiction of references/ connections/ relationships between them materialize? In the process, points, lines, and spaces are created that can be shifted, moved, and dissolved again and again, and to which relational and dynamic meaning is attributed.

- Pause briefly every now and then and record or write memos to capture the process and thus the mapping as a ‘becoming’. If applied in a workshop situation, make the space as open and dynamic as possible so that conversations and exchanges between the participants are possible during the mapping, which will close the gaps between them.

- Reflection: Recapitulate the process and capture emerging thoughts; use this reflection to understand where lines or spaces of inclusion and exclusion have (temporarily) emerged through the multisensory mapping and through the inclusion of different sensory perceptions and connections in the dynamic network. How have different senses been involved? How have lines/ connections/ relationships between different actors been formed and re-formed (territorialized and deterritorialized)? Which (power) dynamics have emerged in this way? In a workshop situation, recapitulate the mapping together by exchanging thoughts and experiences.

Requirements

- Just you or a group – the number of people is flexible,

- Various materials and tools to elaborate your map (e.g. different types and colors of paper, fabric, threads and cords, glue, scissors, or pencils; the more different they are, the more option you have and the more intense you can work on and with your map),

- Sufficient time to do the mapping without time pressure (including the reflection, min. 2 hours).

Example

The following example is based on a workshop on a multidimensional and embodied mapping, addressing the question of the relationship between a person and their hair.

Human hair has always shaped everyday human life, the understanding and perception of subjectivities, places, or communities. Based on self-perception and -attribution as well as attributions by others, certain ideas of hair emerge. These ideas are sorted into categories and groups. Thus, hair is used as a display to organize social and cultural notions and representations of beauty, gender and sexuality, health, age, and faith, between others. People categorize themselves and are assigned to these categories and groups: hair length, color and texture are examples of characteristics through which hair is categorized and linked to specific (characteristic) traits. These characteristics may reflect or designate social roles and delineate who or what ‘belongs’ to corresponding subjectivities, places, or communities. Attributions of self and others may be expressed in and through hair, visualize them and materialize in hair whereby hair appears as a “display for affiliations and belonging” (Boll 2017, p.23-24, own translation). Hair and its connections are thus closely linked to power dynamics that determine social inclusion and exclusion. However, these are rarely reflected in society, which is why an analysis and tracing of power relations in, through and by hair appears to make sense and should serve as an example here.

The multidimensional and embodied mapping was intended to uncover spaces, moments, and situations of exclusion that are shaped and reinforced by power dynamics: Which relations form the connections and perception of one’s hair? Who and what is taking part? How are different actors (co)constructing the connection? And how, why, and what can influence this connection? What can the perception and expression of different senses tell us about powerful dynamics of inclusion and exclusion? Those are just a few examples of questions, framing the mapping process at the beginning. Before the workshop started, I prepared the room so that a diverse range of materials was available (see Fig. 1; it could also be an option to let the participants think about the subject matter in advance and let them bring some additional materials that they seem suitable and that expresses something in this context). Together with the participants of the workshop, we designed and atmosphere of comfort for all of us, by arranging chair and tables and by opening and closing windows and doors.

Figure 1: Table with diverse range of materials for the workshop (own photography)

We started with a short mental journey with eyes closed to take the participants’ attention away from their everyday lives and focus instead on the different sensory perceptions of their own hair. After a few minutes of reflecting and focusing, the participants began to look for materials, some exchanging ideas while others were completely absorbed in themselves. In the meantime, I formulated questions that should help the participants to further engage with the mapping, relating themselves to their hair, with the broadest possible sensory perception: How are you connected to your hair? Through what and how is your hair connected to you? Where do these connections arise and take place? What memories do you have of these connections and your hair? How do these connections express themselves? How do these connections feel? Who or what is involved in these connections?

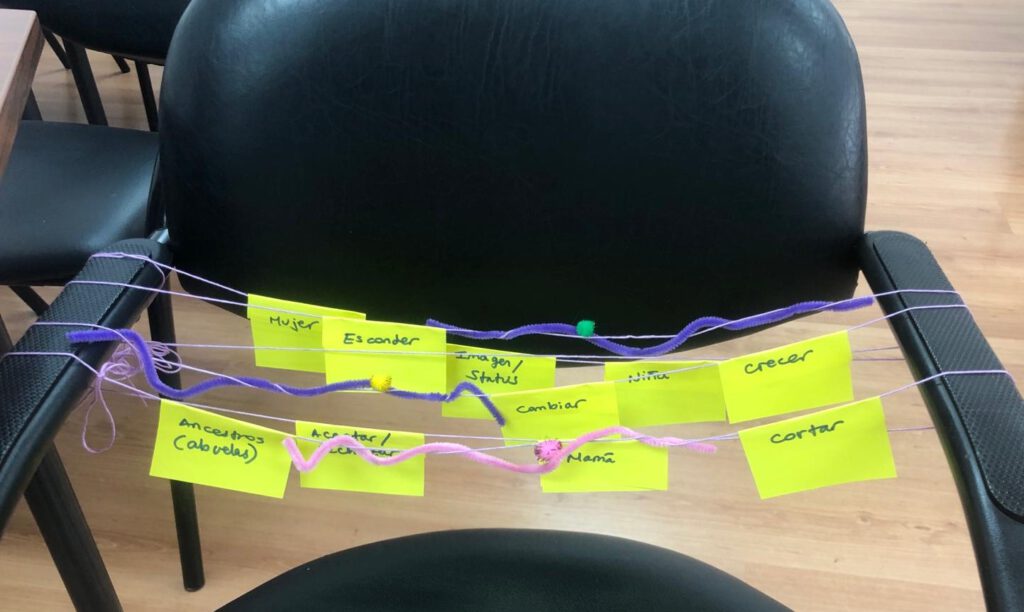

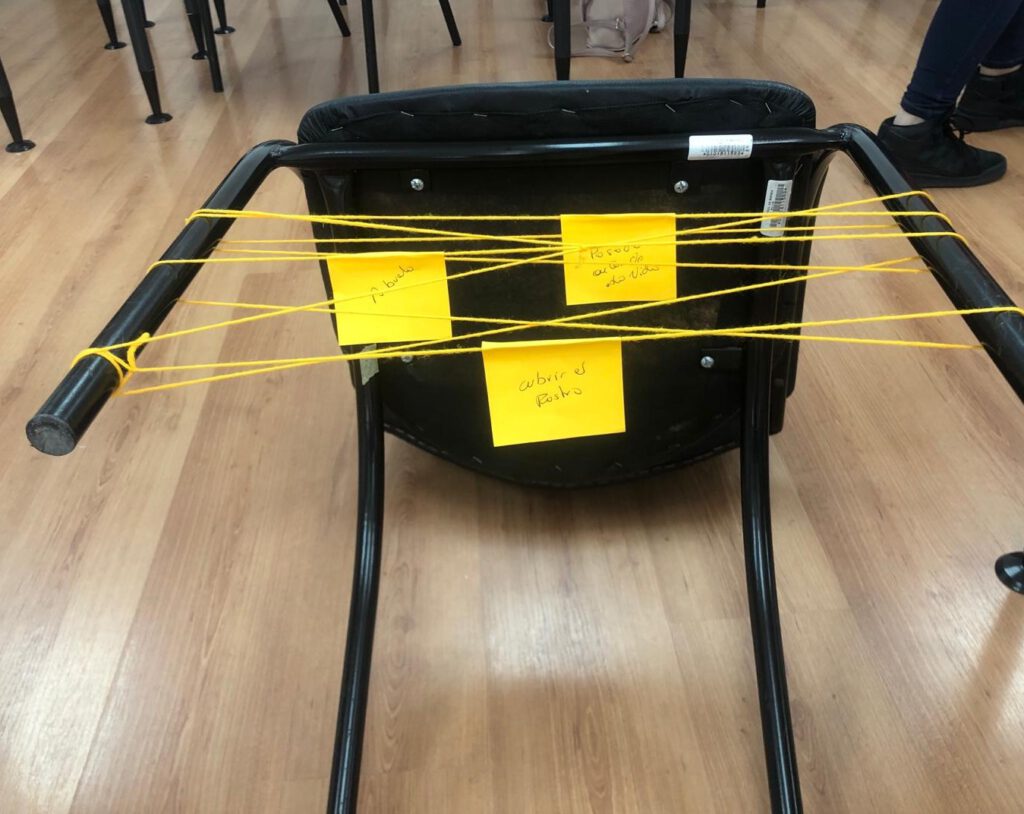

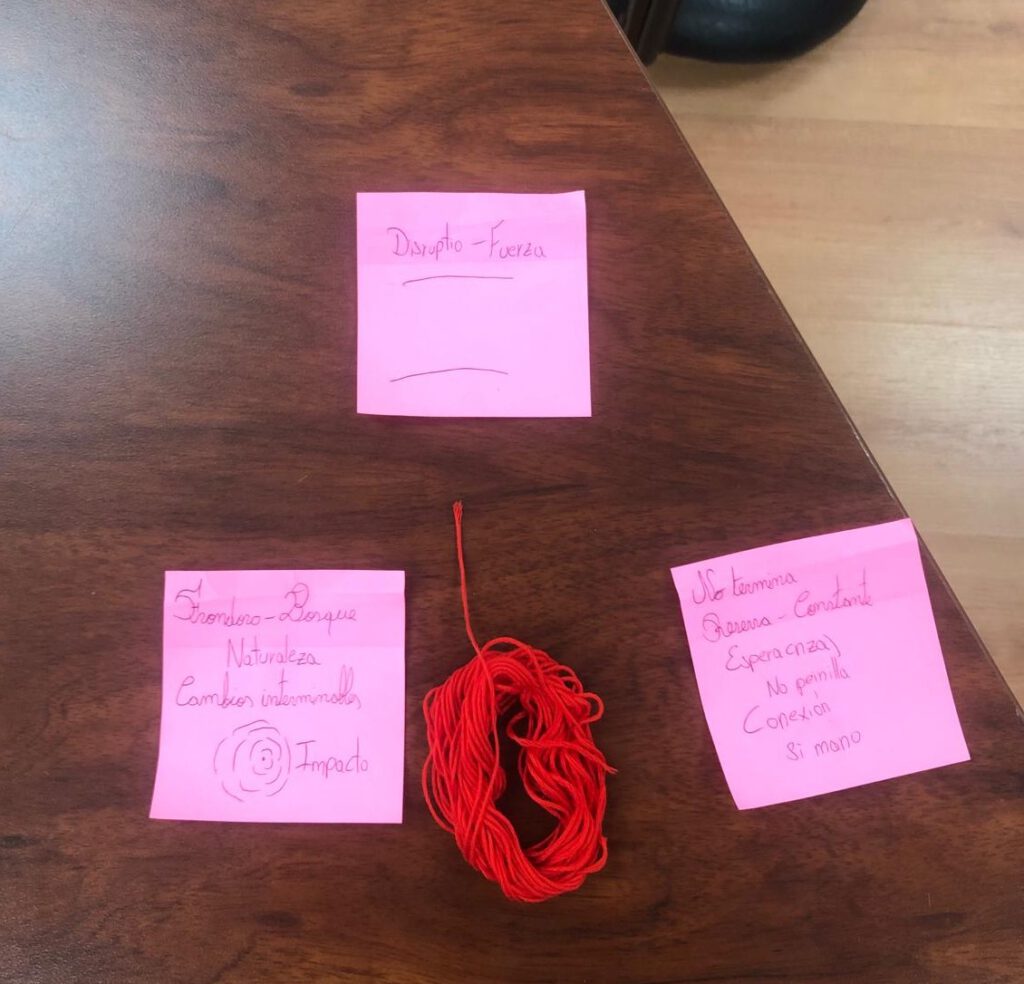

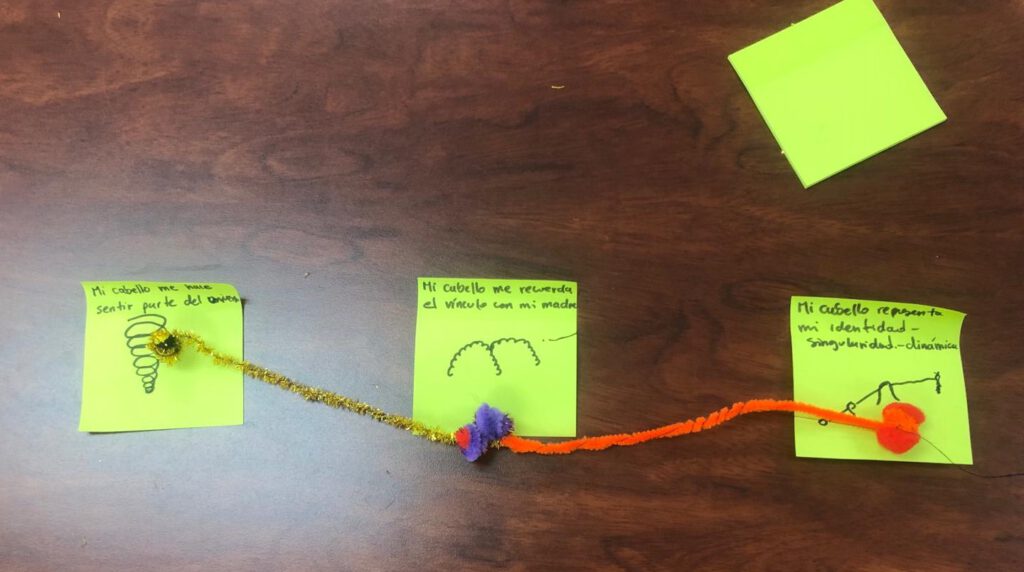

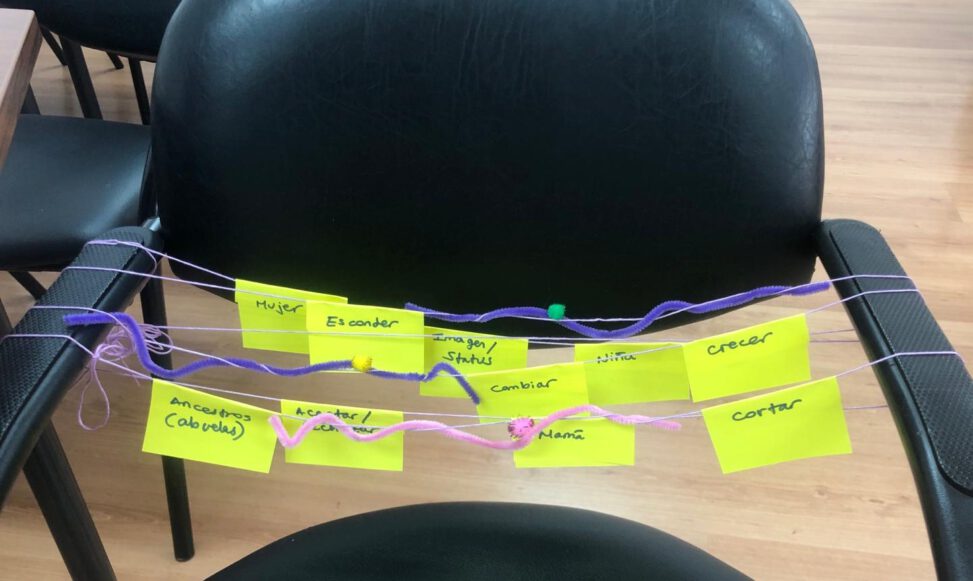

Different materials were used in creating processes of mapping that emphasize lines and spaces of multisensory, relationally embodied, and multidimensional connection and relation through knotting and unknotting, wrapping, and unraveling with different cords, threads, and wires. The mapping spaces were spontaneously created by upturned chairs or their backrests (see fig. 2-3), some participants worked under the tables, others stretched lines between their own arms, which they repeatedly untied and knot anew (see fig. 4). Others worked on the table and laid out their connecting lines there (see fig. 5).

Figures 2-5: Different situations and impressions of a workshop to multidimensional and embodied mapping of the relation of oneself and one’s hair (own photography)

Aspects and perceptions were introduced into the spaces that are created in this way and, following on from lines of connection, different materials and colors, drawings and writing or text elements were used to integrate different actors (see fig. 2-4, the illustrations represent different moments in the mapping process and should not be read as finished maps). While some of the participants were more comfortable writing actors, thoughts and feelings as well as memories and places in words on different pieces of paper and then using different threads and strings to relate them in various ways (see fig. 2-3), one participant focused particularly on the interaction with his own body and wrote down keywords of three corresponding performances on pieces of paper, which he could not present all at the same time due to his physical capabilities (see fig. 4). Another participant tried to capture movements in sketches, then to accompany them with words that he associated with the movements and to connect them with each other using different strings (see fig. 5). Some of the participants talked, told stories, and shared ideas while they knotted and painted, cut, and glued. The process was followed by a round of reflection. We told each other what we wanted to represent in the mapping process and how we represented it, how connections have changed and been reshaped. We also reflected on how this has given us new ideas, how other senses have been addressed or how we have wanted/been able to express ourselves and which connections, relationships, and perceptions we have now become aware of through the process of mapping.

It is particularly important to emphasize that personal stories and experiences that seemed to have been forgotten for a long time emerge again through the process of multidimensional and embodied mapping.

References

Ahmed, S. (2013): The Cultural Politics of Emotion. 1st edition. London: Routledge.

Boll, T. (2017): Soziale Praktiken mit Haut und Haaren. Alltagssemiotik und praktische Ontologie körperlicher Randbereiche. In: sozialmagazin (1-2), pp. 21–27.

Braidotti, R. (2014): Posthumanismus. Trans. Thomas Laugstien. Campus Verlag: Frankfurt.

Braidotti, R. (2021): Posthuman Feminism and Gender Methodology. In: Browne, J. (ed.): Why gender? Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, pp. 101-125.

Braidotti, R. & Fuller, M. (2019): The Posthumanities in an Era of Unexpected Consequences. In: Theory, Culture & Society 36(6), pp. 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276419860567

Clarke, A.E. (2012): Situationsanalyse. Grounded Theory nach dem Postmodern Turn. Springer: Wiesbaden.

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (1987): A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. Trans. Brian Massumi. University of Minnesota Press: Mineapolis.

Dodge M. & Perkins, C. (2008): Reclaiming the Map. In: Environment and Planning 40, pp. 1271-1276. https://doi.org/10.1068/a4172

Kollektiv Orangotango+ (eds.) (2018): This is not an atlas. Transcript: Bielefeld.

Longhurst, R. (1997): (Dis)embodied geographies. In: Progress in Human Geography 21(4), pp. 486-501. https://doi.org/10.1191/030913297668704177

Meißner, K. (2019): Relational Becoming – mit Anderen werden. Transcript: Bielefeld.

Misharina, A. & Betts, E. (2023): The Embodied City: A Method for Multisensory Mapping. In: Landeschi G. & Betts, E. (eds.): Capturing the Senses, Qualitative Methods in the Humanities and Social Sciences, Springer Nature: Cham, pp. 237-264.

Perkins, C. (2017): Critical cartography. In: Kent A. & Vujakovic, P. (eds.): The Routledge Handbook of Mapping and Cartography. Routledge: London.

Renold, E. & Mellor, D. (2013): Deleuze and Guattari in the Nursery: Towards an Ethnographic Multi-Sensory Mapping of Gendered Bodies and Becoming. In: Coleman, R. & Ringrose, J. (eds.): Deleuze and research methodologies. Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh, pp. 23-41.

Rieger, J. (2016): Doning Dis/ordered Mapping/s: Embodying Disability in the Museum Environment. Doctor Thesis at University of Alberta, Department of Human Ecology, Alberta, Canada.

Rieger, J. (2023): Doing Embodied Mapping/s (EM). In: International Creative Research Methods Conference (ICRMC), 2023-09-11 – 2023-09-13, Manchester, UK.

Rieger, J.; Devlieger, P.; van Assche, K. & Strickfaden, M. (2022): Doing Embodied Mapping/s: Becoming-With in Qualitative Inquiry. In: International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21, pp. 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221137490

Rosaldo, M. (1984): Toward an anthropology of self and feeling. In: Shweder, R. & Levine, R. (eds.): Culture theory. Essays on mind, self and emotion. 1. Publ. Cambridge Univ. Press: Cambridge, pp.137–157.

Ruck A. & Mannion, G. (2020): Fiednotes and Situational Analysis in Environmental Education Research: Experiments in New Materialism. In: Environmental Education Research 26(9-10), pp. 1373-1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1594172

Leave a Reply