Getting crafty in and beyond academia

Authors:

Nora Mariella Küttel & Melike Peterson

Citation:

Küttel, N. M., Peterson, M. (2024): Zines. Getting crafty in and beyond academia. In: VisQual Methodbox,

URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2023/11/30/zines/

Essentials

- Background: Zines and zine-making correspond with a “creative turn” (Hawkins 2019) in geography and feminist approaches to visual and creative methods, which seek to explore more active forms of knowledge production and empathetic and transparent research practices (Küttel/Peterson 2023).

- Aim: While the language of zines is more personal, their content and aims are often political, and geographers can use zines to visualise and narrate the political from individual experiences and perspectives (Bagelman/Bagelman 2016).

- Usefulness: Zines are produced on various topics and in diverse formats and designs. Their “blurred borders” (Lymn 2010) lend themselves well to visualising e.g. aspects of intimacy and connection, sensuality, emotions, and atmospheres.

Description

Zines are non-commercial, non-professional, limited-circulation magazines that are produced, published, and distributed using voluntary unpaid labour (Duncombe 1997).

Rooted in a DIY ethos, zines can be traced back to the 1920s, when small self-made collages were prevalent in artistic and philosophical movements. However, it was not until the 1930s that zines emerged as a medium in their own right, finding a niche in science fiction communities. This development continued through the North American punk rock era of the 1970s and the resurgence of the riot grrrl movement in the 1990s, particularly with the publication of personal and political zines by female and younger creators (Bagelman/Bagelman 2016).

Unlike mainstream publications, zines are free from editorial constraints and the pressures of marketability. They embrace the idea that every voice has value, transcending the limitations imposed by money, status, or talent (Leventhal 2006). This allows for zines to be “written on all manner of topics and produced in a variety of formats and designs” (Chidgey 2006: 1). This means that zines often reflect the expressions and thoughts of everyperson – those “who are nothing at all to dominant society, whether because they are too regular, or because too far outside what is regular” (Duncombe 1997: 25-26). This way, zines not only serve as a platform for self-expression, but also have political significance, aligning with the feminist claim that personal experiences and narratives are always political (Bagelman/Bagelman 2016). Zines also occupy unique spaces, both physically and conceptually, as they exist in the “spaces in between and around those that are fixed in space” (Lymn 2010: 3), fostering a medium where creativity knows no boundaries and diverse voices can be heard. This diversity of expression is also why zines have a particular quality of intimacy and connection between author and reader. They contain, narrate, and reflect emotions and atmospheres and, at the same time can create them through their self-determined and personalised style.

These qualities are also of interest when thinking about zines in academia. Looking more closely at zines in academic teaching, they have several potentials that are in line with feminist pedagogy, including participatory learning, recognition of personal experiences and the development of critical thinking (Creasap 2014; Valli 2021). Valesco et al. (2020: 349) conclude that “zines are a powerful methodology and output by which one can reflect meaningfully on their research and their positionality“. Zines can slow down the classroom and create a joyful, caring, and solidary counter-project to the neoliberal university, which thrives on a fast pace and high volume of output (Bagelman/Bagelman 2016). The practice of zine-making could “help students connect theory and everyday life” (Creasap 2014: 166) in new and meaningful ways, fostering a deeper engagement with both.

Using zines as a research method can present a number of challenges. Zines require artistic effort and a certain level of artistic and creative skill to create. This can be challenging for some researchers who may not have expertise or experience in methods that rely on the visual or creative arts. Zines, and the open-endedness and unpredictability of their outcomes, can also be seen as an “awkward addition” (Küttel/Peterson 2023) to more traditional and established research methods. And while zines prioritise the “felt value” (Watson/Bennett 2021) and are an anti-mainstream medium, this may limit their acceptance within wider academic communities that value more conventional and standardised research outputs. Finally, zines are typically produced and distributed in small quantities, often in analogue format, which may mean that their reach and impact is more limited compared to more established and recognised forms of publication.

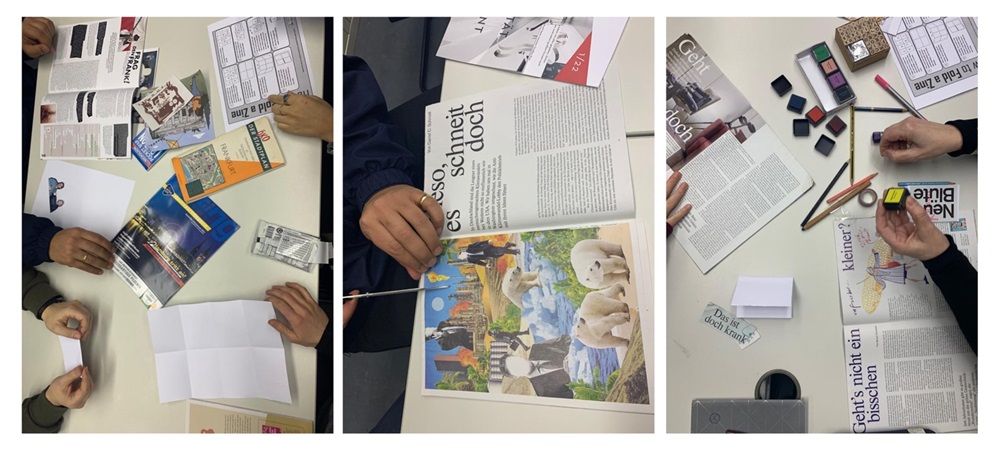

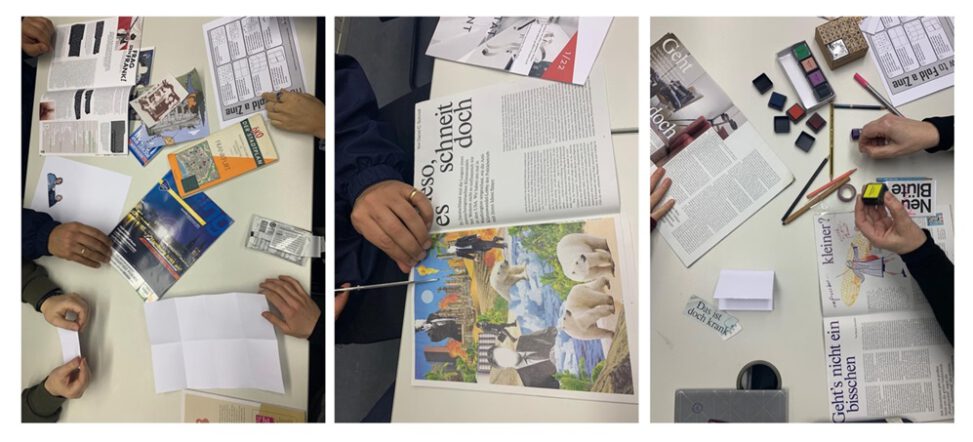

Image 1: Creating zines at the 2023 Neue Kulturgeographie Conference (NKG) in Halle (Photos by the authors)

Procedure

Anyone can make zines. Zines are well suited to working with diverse groups and communities and with different goals in mind. To give a sense of what the process of making a zine might look like, we will discuss how researchers might go about creating a zine to communicate issues and findings from their research to a wider audience:

- Step 1: Think about what you want to communicate in your zine and consider the chronology of the story you want to tell. Consider who your audience will be – this may influence the style, choice of language and materials used in your zine.

- Step 2: Collect materials – lots of them! You can use anything that resonates with you and works in/with your zine. When we run zine-making workshops, we like to bring lots of visual materials – from magazines to vinyl covers, maps and pamphlets, as well as a variety of pens, stamps, and tape.

- Step 3: Browse the materials. Be inspired and guided by what you find. Cut out what speaks to you; this could be objects, shapes, colours, people, words, letters, patterns, signs, or something else entirely.

- Step 4: With your story and audience in mind, assemble the materials into your zine and add as much or as little written text as you like. And don’t forget to enjoy the process – it may open up new ways of thinking about your research.

- Optional: Talk about the zines with the people you have made them with.

Requirements

- For your zine, it is flexible who is in the mix – it could just be you or a group of people like students in a classroom, research participants or a team of researchers reflecting on their work.

- Various materials and tools for crafting your zine

- Sufficient time to think, collage, cut and paste things together

Example

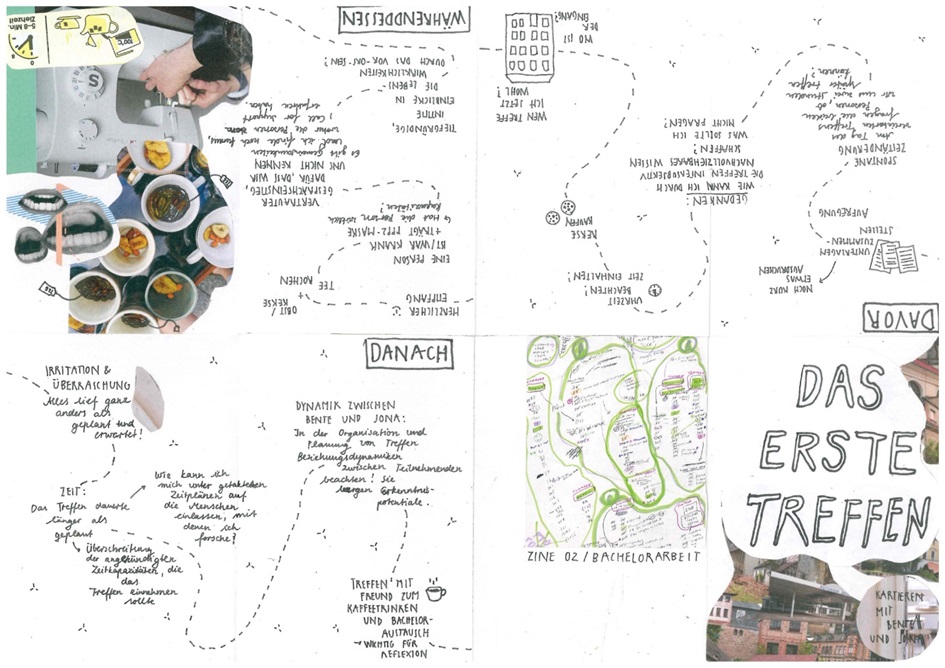

The following is an example of a zine that graduate student Hannah Schnelle used as a tool for reflection in her Bachelor thesis. Her thesis explores how critical mapping can be used as a method of feminist-geographical housing research to examine the use of technology in domestic care work (Schnelle 2023). Hannah created a total of four zines: one as a starting point for her research, two produced after mapping sessions and a final one in which she grapples with her role as a researcher, probing questions related to positionality, power dynamics and responsibility.

Image 2: Hannah’s reflections on her initial research encounter (Schnelle 2023)

The zine depicted here captures Hannah’s reflections on her initial research encounter. Created before, during and after a mapping session with two research participants, the zine became a medium through which she reflected on various moments and emotions tied to the preparation and execution of the mapping session. The insights documented in the zine not only shaped subsequent mapping sessions with other participants but also influenced the process of data analysis.

In her own words, Hannah articulated her rationale: “Nevertheless, from my perspective, continuous reflection on research ethics should be an integral part of the research process. … Hence, I decided to start creating zines in August 2023. Based on my own experiences, four zines materialised throughout the research journey, providing me with a platform to document reflections that could not find a place in the thesis. This creative and thematically organised outlet enabled me to comprehend my personal attributes, decisions, privileges, and perceptions in the research process, situating them within the broader context of the study. The zine format not only allowed me to articulate my thoughts textually but also visually (Küttel & Peterson 2023: 100f.). To foster genuine communication regarding my experiences and align with the resistant character of zines (Küttel & Peterson 2023: 101), I included the zines in the appendix of my thesis“ (Schnelle 2023: 36f., own translation).

Zine 02: The initial research encounter (Schnelle 2023)

Useful Ressources

Suggested Tools

- Various types of print media, including newspapers, magazines, maps, pamphlets, photos and illustrations

- Paper to fold the zines with

- Pens, scissors, and glue sticks

- Paints, stamps, stencils, and tape

- Optional: Photocopier to scan and copy the zines

References

Bagelman, J./Bagelman, C. (2016) ZINES: Crafting change and repurposing the neoliberal university. ACME 15(2): 365-392. https://acme-journal.org/index.php/acme/article/view/1257

Creasap, K. (2014) Zine-Making as feminist pedagogy. Feminist Teacher 24(3): 155-168. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/femteacher.24.3.0155

Duncombe, S. (1997) Notes from the underground: Zines and the politics of alternative culture. London: Verso.

Hawkins, H. (2019) Geography’s creative (re)turn: Toward a critical framework. Progress in Human Geography 43(6): 963-984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518804341

Küttel, N./Peterson, M. (2023) Schneiden, Kleben, Reflektieren: Zines und das Erstellen reflexiver (Forschungs-)Räume. In: Singer, K. et al. (Hg.) Artographies: Kreativ-künstlerische Zugänge zu einer machtkritischen Raumforschung. Bielefeld: transcript.

Leventhal, A. (2006) The politics of small: Strategies and considerations in zine preservation. Graduate Student Panel: Preservation of New Media. Montreal: McGill University. https://www.docam.ca/images/stories/pdf/seminaires/2006_02_anna_leventhal.pdf

Lymn, J. (2010) When Zines meet Archives. Above and Below Ground Collections. Artlink 30(2): 47-48.

Schnelle, H. (2023) Kritisches Kartieren im Wohnraum als Schauplatz technisierter Sorgearbeit – Ein methodologischer Beitrag zur Wissensproduktion in feministisch-geographischer Wohnforschung. Unveröffentlichte Bachelorarbeit am Institut für Geowissenschaften und Geographie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg.

Valli, C. (2021) Participatory dissemination: bridging in-depth interviews, participation, and creative visual methods through Interview-Based Zine-Making (IBZM). Fennia 199(1): 25–45. https://doi.org/10.11143/fennia.99197

Velasco, G./Faria, C./Walenta, J. (2020) Imagining environmental justice ‚across the street‘: Zine-making as creative feminist geographic method. GeoHumanities 6(2): 347-370. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2020.1814161

Watson, A./Bennett, A. (2021) The felt value of reading zines. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 9: 115-149. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41290-020-00108-9

Leave a Reply