Beyond Mere Methods: Thematic and Critical Engagements with Feminist C/artographies

Author:

Singer, Katrin; Schmidt, Katharina

Citation:

Singer, K.; Schmidt, K. (2026): Beyond Mere Methods: Thematic and Critical Engagements with Feminist C/artographies. In: VisQual Methodbox. https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2026/02/17/feminist-c-artographies-2/

Essentials

- Feminist C/artographies is a methodological approach that combines feminism, critical cartography, and creativity, both theoretically and practically.

- Maps as an Embodied and Collective Process: Feminist C/artographies emerge as a continuous process and product of embodied and situated exchange and collaboration. They invite us to question the creation of maps as a purely static representation and to view them as a dynamic, collective, and sensitive dialogue that unfolds over time and through care.

- Challenging Patriarchal Structures: A commitment to feminist c/artographies entails dismantling patriarchal structures. Our maps aim to serve as tools for resistance, challenging the status quo and advocating for equity and justice grounded in feminist care ethics.

- Feminist C/artographies are unique: There is no singular path in feminist c/artographies, just as “there is no single-issue feminist struggle” (Lorde 1984: 138). Every c/artographic practice tells its own story as an outcome of a situated, context and place-based process.

Description

“What does it mean when the tools of racist patriarchy are used to examine the fruits of that same patriarchy? It means that only the most narrow perimeters of change are possible and allowable” (Lorde 1984: 110/111)

Inspired by Audre Lorde, we recognise the importance of learning to critique and deconstruct maps that have historically supported patriarchal understandings and claims to spaces and places. This ongoing process requires us to examine the effects of both classical and feminist cartographic semiology —such as how black lines (re-)produce the idea of national border regimes, and how the bird’s-eye view creates a sense of distance in our spatial orientation. We are not above the earth, but inherently part of it. In line with Virginia Woolf’s (1938) thinking, we assert that our feminist c/artographies have never constituted a country to claim and own, and never will. Or as Dionne Brand puts it so succinctly, “I don’t want no fucking country, here or there and all the way back, I don’t like it, none of it, easy as that” (Brand cited in McKittrick 2006: ix). Why do maps seldom represent this place-based perspective beyond border regimes?

Imperial endeavours to claim, label, and own entire continents form a historical explanation. Western world maps served as spatial tools that supported, navigated through and reinforced this imperial worldview. Understanding the power dynamics and historical contexts behind projections, colours, lines, categorisation, framing, and cross-hatching in maps enables us to engage with cartographic traditions in geography. It also encourages us to critically question these conventions through the works of critical and postcolonial cartographers (Harley 1989, Huffmann 1997, McKittrick 2021, Rose-Redwood 2020, etc.). Through their deconstruction of the power of maps, a possibility emerges to develop a critical consciousness that reads maps differently.

However, a critical reading of maps does not necessarily include feminist perspectives. Feminist perspectives on critical cartography have been pointing out the representation of an androcentric view of the world, highlighting and speaking to white male power in producing, distributing, and explaining their world through maps (Brown & Knopp 2008; Elwood & Leszczynski 2018; Kelly & Bosse 2022, Olmedo & Kayiganwa 2024, Rodó-de-Zárate 2014, Schmidt 2024, etc.). As a way of countering androcentric cartographic representations, feminist mappers around the world have been engaging with cartographic practices to put women and queer people on the map by appropriating or rejecting the tools of classic cartography (see the listing of selected examples at the end of the article).

With the idea of feminist c/artographies in mind, we raise the question of how to enrich critical cartography with intersectional feminist perspectives while also challenging the narrow perimeters of classical cartography by creating alternative maps that represent feminist understandings of space and place.

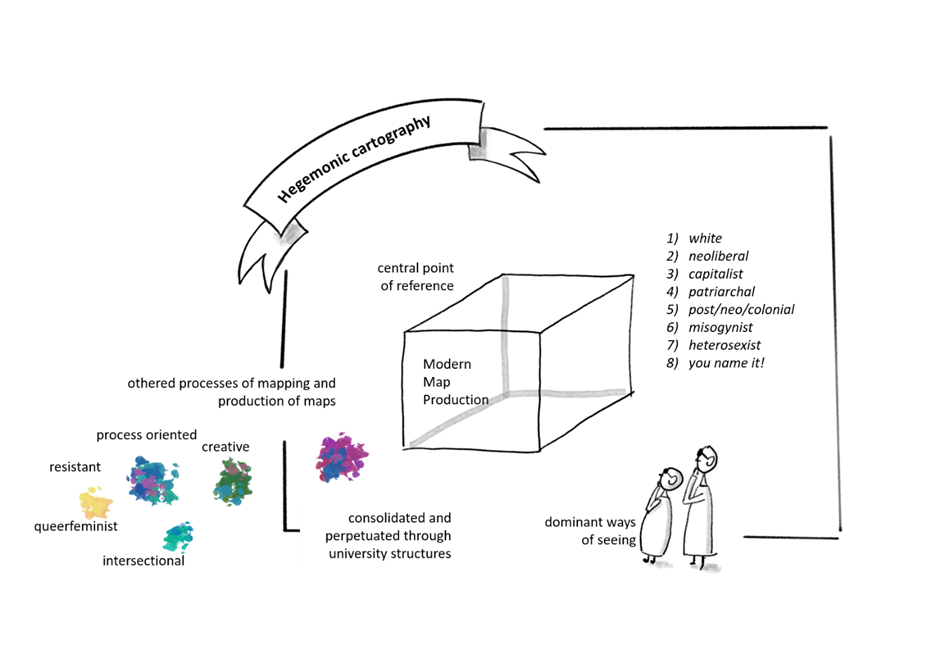

In our engagement with critical cartography and feminism, this question led us to embrace creativity as an approach to rethink and redraw the idea of what a map should look like, one that is not only able to challenge the patriarchal worldview but also the canon and hegemony of cartography itself (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1: The Structure of Power in Cartography © Singer/Schmidt, 2026

Drawing on our own engagement with feminist, creative, and critical mappings, we observed over time that some basic ideas and arguments seem to repeat themselves, appearing with different weightings across various mapping projects. Based on these observations and recent academic discussions, we identified some crucial moments, mechanisms, and ideas within mapping processes that help us make a mapping project more feminist and cartographic. And, of course, a lot is definitely missing, and we hope you will mention it in further discussions. In the following paragraphs, we therefore like to highlight and share the significance of reflexivity, positionality, creativity and relationality.

Relationality/Process

Drawing on feminist and postrepresentational theories, one crucial shift within Western critical cartographic thinking is noted (Kitchin & Dodge 2013). This shift moves from viewing maps solely as products, results, or outcomes to viewing them as processes, journeys, or dialogues. The mapping process then stands in relation to people, places, dialogues and practices expressed through mapping. Feminist c/artographies seek to resonate with the people involved in the mapping process, meaning that what matters to them cannot be predetermined but emerges through collaborative dialogue. While the final map is undoubtedly significant, the process of creating it is equally important. This kind of shift transforms the very practice of mapping, bringing power relations within mapping processes to the forefront and allowing for their active negotiation. This can mean, for example, that all people involved in the mapping become cartographers themselves, that the interests and aims beyond the mapping are openly discussed, and that discussion and collective reflection on space take precedence over the map itself. Hierarchies, privileges, and situated knowledge are inherent parts of every mapping project. Being aware of them, discussing them openly, and naming them are essential steps toward finding a collective way to address and balance power and inequalities throughout the mapping process.

In line with feminist discussions of slow scholarship (Mountz et al. 2015; Fung 2025), we highlight that mapping requires patience and care. It is a slow process that demands deep engagement, deep listening, and openness to emotions, vulnerability, failure, and learning. Meghan Kelly and Amber Bosse remind us that taking time for reflection and engaging in dialogue with others is essential, even amidst the busyness of daily life and the neoliberal pace of academic knowledge production. Regularly pressing pause (ebd. 2022) to reflect and to ask for feedback can lead to meaningful reflections and changes in your mapping process. Feminist care ethics, which inform how we engage, design, and create dialogues, reveal the necessity of establishing a careful, multifaceted practice that reflects the diversity of experiences and perspectives shaping feminist mapping (see the homepage of the Manifesto Playlist)[1].

Positionality

Many postcolonial, feminist, and critical mappers highlight the importance of dealing with one’s own mapping practices and the ambivalent fact of performing the powerful role of a map creator or responsible person in a mapping process, since it entails significant responsibility. Even though many critical projects take on responsibilities and aim to embody vulnerabilities, emotions, and critiques, we still want to highlight that all maps—including decolonial, feminist, critical, and creative ones—can obscure and exclude. No map can be considered “innocent”, as underlying narratives and hidden scripts significantly influence representation. We therefore consider all maps as situated. This is when we draw on feminist theories of standpoint (Harding 2004), positionality (Faria & Mollet 2016), and situatedness (Haraway 1995) to illuminate these hidden dynamics and to critically examine who determines what is represented and how it is articulated.

Being the mapping person in charge, we face hard decisions, such as whether to use specific mapping tools, base maps, and software that we criticise, or how to navigate narrow study curricula, strict project obligations, and, above all, the pressures of daily life. Our lives and our work are still highly influenced by patriarchy. Since only a few of us can make a living from feminist critical c/artographies, these struggles are substantial. To position us and our mapping projects within the relevant context, expressing these challenges and thoughts can be valuable. Some cartographers, therefore, choose to include specific information directly on the map, while others provide accompanying texts (Kelly & Bosse 2022).

By sharing mapping processes in solidarity and making knowledge accessible and transparent, feminist c/artographies can aim to reflect a plurality of voices and experiences, creating pathways for situated, inclusive and transformative practices in cartography. These are eager objectives, and we are very likely to fail them in one way or another. Failing is an inherent part of this journey; we must listen openly to feedback, learn from our missteps, share our insights, take responsibility for our mistakes, and have the courage to try again (Singer 2019: 141-170). We want to emphasise that the goal is not to create the perfect feminist counter-map or to develop an ideal feminist mapping process; we believe such perfection does not exist. The maps we encounter in our academic and daily lives often serve as tools of the powerful, deeply embedded within complex power dynamics.

Creativity

In recent discussions of geography, the role of creativity is gaining momentum (Hawkins 2019, Noxolo 2018). By viewing cartography as a creative methodology, we can open up space for experimenting with the ontology of maps and for reinventing, appropriating, or reimagining their ideas, forms, and symbols in different ways. This is an exciting possibility for mapmakers, and we can observe a growing artistic engagement with cartography and maps in and beyond the discipline of geography (see section useful resources). It also encompasses learning from artists who have been developing creative mapping practices outside the discipline for a long time, such as Gloria Anzaldúa. However, a solid grounding and understanding of cartographic principles seems crucial for a creative rethinking and redoing of cartography, as they invite thoughtful engagement with classical cartography rather than dismissing it outright. To formulate a critique of “the old,” we have to be aware of how “the old” is functioning and what the point of critique actually is. We recognise that creativity alone does not automatically translate into feminist or power-critical practices. A map can be creative and disruptive of classical cartographic tools; however, this does not necessarily mean that the process of map-making was careful or thoughtful. And that is perfectly okay. A map is allowed to be artful and creative—and that alone can be enough.

In the context of feminist c/artographies, though, we, as academics aiming to engage with the cartographic community within or beyond the academy, believe that the critical potential of creativity is often limited when maps focus solely on playful design or aesthetic innovation. We see creativity as a source of inspiration—an embodied language and a tool that helps us move beyond patriarchal rules of cartography to represent feminist issues and struggles over space and place in ways that would otherwise be marginalised or overlooked.

Reflexivity

As a last point, we would like to state the obvious: reflexivity seems to be the crucial cross-cutting issue in all aspects discussed so far. Whether we focus on the process of making maps, on the way we position ourselves towards our own maps or within our own map-making processes, or on how we creatively engage with ambiguities when considering whether to leave the idea of the map or reclaim it. Reflective processes are at the centre of developing feminist c/artographies that undertake methodological work that transcends mere techniques. Engaging in mapping requires deliberate theoretical and methodological reflection, recognising that mapping is a profound process of knowledge production intertwined with power relations and socio-ecological struggles.

Procedure

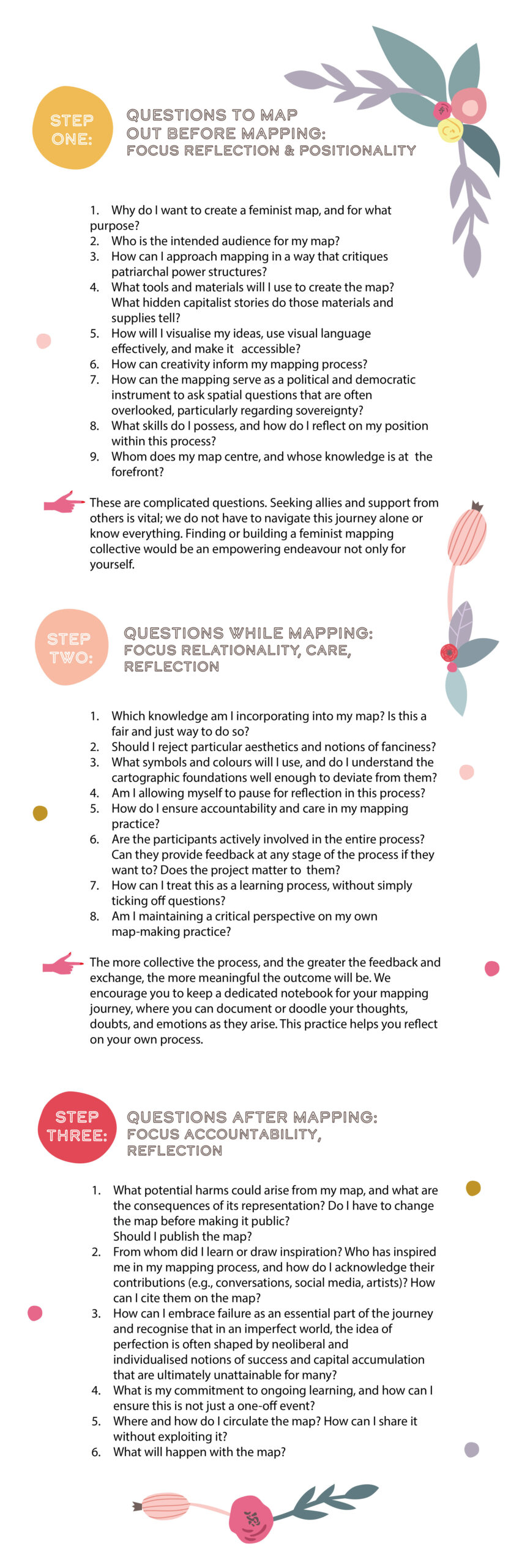

Since there is not ‘the one’ true manual for feminist c/artographies but rather multiple experiences and possibilities that necessitate multiple mapping approaches and maps, we decided for this section to share some questions with you instead of providing one methodological answer. Over the years, we have encountered a colourful bouquet of complex questions that accompany us on every mapping project. And every time we do find different answers to them. While some answers led us to failure, some to refusal, some brought us progress, and others sent us right back to the beginning, all of them impacted our mapping projects, helping them grow carefully, slowly, creatively, and critically along with them. We hope this collection of questions helps you move beyond traditional notions of what a map should be, enriching your cartographic practice and guiding your mapping process in a feminist c/artographic way.

Limitations

In approaching feminist c/artographies, it is essential to recognise certain limitations that can influence the mapping process as a whole. One significant concern is the danger of engaging in mapping simply for the sake of it or for the fanciness of it. As Paul Schweizer and Severin Halder highlight, this approach can detract from the meaningful engagement necessary to create maps that resonate with the communities and territories they represent (ebd. 2024). Another critical question to consider is whether another map is truly necessary. In a world saturated with maps and short attention spans, it is vital to reflect on the value and purpose of creating yet another representation in the form of a map. Does the map deeply matter to the people you want to work with?

Our reflection on the feminist language of mapping deepens through these considerations: Do we really want to learn this language and put in the necessary time to become skilled in it? Furthermore, it is crucial to scrutinise whether the maps we produce can genuinely be called feminist. Would it be more appropriate to refer to them as participatory maps, mental maps, creative maps or mind maps? It is important to ask yourself this question so that the term “feminism” does not become a hollow metaphor but remains grounded in its powerful pursuit of justice and democracy (Tuck & Yang 2012). Another important consideration is the participants’ comfort in the mapping process. Are they at ease with it, and is mapping a meaningful spatial justice tool for them? In case it is not, what other methods could be applied? What do your participants want to do, what do they love? Listening to and concentrating on the voices of those involved is fundamental to the integrity of the mapping practice and the chosen method.

Lastly, we want to address the risk of exploitation inherent in mapping projects. How can we avoid allowing our work to be co-opted by neoliberal and patriarchal interests? Remain vigilant about how our maps may be consumed or repurposed, ensuring that they align with the values of equity, open access and justice that feminist c/artographies strive to uphold. In conclusion, recognising these limitations encourages a more reflective and ethical approach to feminist c/artographies, guiding practitioners to create maps that are not only visually compelling but also socially responsible and empowering. So, in the end, you and your co-mappers have to decide whether to lose the map or reclaim it.

Useful Resources: (not only) Feminist C/artographies – A Small, Incomplete Selection to Get Started

Documentary Film:

“Dreading the Map” by Sonia E. Barrett with Pat Noxolo Watch here

Handbook:

Fearless Collective: Fearless Futures. A Feminist Cartographers Toolkit. Access the toolkit

Feminist C/artographers and Groups:

- Colectivo Miradas Criticas del Territorio desde el Feminismo

- The Geography and Gender Research Group at Autonomous University Barcelona produces inspiring feminist and cartographic work: Website

- Publications and lectures by Meghan Kelly, focusing mainly on digital mappings and GIS: Website

- Talks and publications by Elise Olmedo, emphasising sensitive and artistic mappings: Website

- On the homepage of the *AG KGGU* (Working Group Critical Geographies of Global Inequalities G), you’ll find a *Karto FemGeo* Brochure and a fantastic Atlas 2020 both created by students:

- A Feminist Geographical Roundmail (Nr. 89) on the topic of “Mapping Stories of Feminist Mapping”: Read here

- The works of artist Firelei Báez: Watch here

- And many more…

Not Just for Young People:

“Yuki~you. A Flow-Motion of Critical Cartography” (from Hamburg’s Kollektiv Kartattack) Watch here

Basics and Educational Resources:

- Arte – How Powerful Are Maps? Watch here

- Counter-Cartography: What Google Maps Doesn’t Show You Watch here

- Manifesto Playlist: Read here

General Resources:

- The Orangotango Collective homepage offers many materials and links: Visit here – Publications: “Not an Atlas”: Transcript Verlag – “Beyond Molotovs”: Transcript Verlag

- Iconoclasistas: Website

- Visionscarto.net

- More from us: Artographies – A creative, critical approach to space research: Link to Artographies

References

Brown, M. & Knopp, L (2008): Queering the map: The productive tensions of colliding epistemologies. In: Annals of the Association of American Geographers, 98:1, 40–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/00045600701734042

Faria, C. & Mollett, S. (2016): Critical feminist reflexivity and the politics of whiteness in the ‘field’. In: Gender, Place & Culture, 23:1, 79-93. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.958065

Fung, Z. (2025): Who can “slow down” in the neoliberal academy? Reflections on the politics of time as an early-career feminist geographer in Switzerland. In: Geogr. Helv., 80, 163–172. https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-80-163-2025

Haraway, D. (1995): Situiertes Wissen. Die Wissenschaftsfrage im Feminismus und das Privileg einer partialen Perspektive. In: Donna Haraway (ed.): Die Neuerfindung der Natur. Primaten, Cyborgs und Frauen, Frankfurt a.M./New York: Campus Verlag, 73-97.

Harding, S. (ed.) (2004): The Feminist Standpoint Theory Reader. Intellectual and Political Controversies, New York/London: Routledge.

Harley, J. B. (1989): Deconstructing the Map. In: Cartographica, 26:2, 1-20.

Hawkins, H. (2019): Geography’s creative (re)turn: Toward a critical framework. In: Progress in Human Geography, 43:6, 963-984. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132518804341

Huffmann, N. H. (1997). Charting the other maps: Cartography and visual methods in feminist research. In: Jones, J.P.; Nast, H. J. & Roberts, S. M. (Hrsg.): Thresholds in feminist geography: difference, methodology, and representation. Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 255–283.

lwood, S. & Leszczynski, A. (2018): Feminist digital geographies. In: Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 25:5, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2018.1465396

Kelly, M. & Bosse, A. (2022): Pressing pause, “doing” feminist mapping. In: ACME: An International Journal for Critical Geographies, 21:4, 399–415. https://doi.org/10.14288/acme.v21i4.2083

Kitchin, R. & Dodge, M. (2013): Unfolding mapping practices: a new epistemology for cartography. In: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 38, 480-496. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2012.00540.x

Lorde, A. (1984): Sisters Outsider. New York: Crossing Press.

McKittrick, K. (2006): Demonic Grounds. Black women and the Cartographies of Struggle. Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press.

Mountz, A.; Bonds, A.; Mansfield, B.; Loyd, J.; Hyndman, J.; Walton-Roberts; M.; Basu, R.; Whitson, R.; Hawkins, R.; Hamilton, T. & Curran W. (2015): For Slow Scholarship: A Feminist Politics of Resistance through Collective Action in the Neoliberal University. In: ACME, 14:2, 1235 – 1259. https://doi.org/10.14288/acme.v14i4.1058

Noxolo, P. (2018): Flat Out! Dancing the city at a time of austerity. In: Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 36:5, 797-811. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818782559

Olmedo, É. & Kayiganwa, E. (2024): The lining of maps: mapping the intimacies of the cartographic processes. In: International Journal of Cartography, 10:3, 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/23729333.2024.2416883

Rose-Redwood, R.; Blu Barnd, N.; Lucchesi, A. H.; Dias, S. & Patrick, W. (2020): Decolonising the Map: Recentering Indigenous Mappings. In: Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization, 55:3, 151–162. https://doi.org/10.3138/cart.53.3.intro

Rodó-de-Zárate, M. (2014): Developing geographies of intersectionality with relief maps: Reflections from youth research in Manresa, Catalonia. In: Gender, Place and Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, 21:8, 925–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2013.817974

Schmidt, Katharina (2025): Corporeo-cartographies of Homelessness. Women’s Embodied Experiences of Homelessness and Urban Space. In: Gender, Place & Culture, 23:3, 366-388. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2024.2312368

Schweizer, P. & Severin H. (2024): Don’t Believe the Mapping Hype! Three Steps Back for an Engaged Cartography. In: The Routledge Handbook of Cartographic Humanities. Rossetto, T. and Lo Presti, L. London: Routledge, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003327578-7

Singer, Katrin (2019): Confluencing Worlds. Skizzen zur Kolonialität von Kindheit, Natur und Forschung im Callejón de Huaylas, Peru. Dissertation. Institut für Geographie, Universität Hamburg. https://ediss.sub.uni-hamburg.de/handle/ediss/6315

Tuck, Eve & Yang, Wayne K. (2012): Decolonisation is not a metaphor. In: Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, 1 :1, S. 1-40.

Woolf, Virginia (1938): The Three Guineas. London: Hogarth Press.

[1] Thank you Michèle von Kochemba for sharing this with us.