A Method based on Aby Warburg’s “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne”

Author:

Suchy, Juliane

Citation:

Suchy, J. (2024): Using Picture Atlas Panels beyond Art History.

A Method based on Aby Warburg’s “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne”. In: VisQual Methodbox, URL: https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2024/11/05/using-picture-atlas-panels-beyond-art-history/

Essentials

- Background: The “Mnemosyne” picture atlas approach was initially developed by German researcher for art and culture studies Aby Warburg in the early 20th century.

- Aim: Discovering visual patterns of meaning in pictures over the time, exploration of presentation strategies.

- Exploration: The “Mnemosyne” picture atlas (German: Bilderatlas) is an open-ended process of assembling pictures and elaborating on the patterns embedded in them socially resp. culturally .

Description

The growing importance of visuals in current global communication processes is sometimes termed as “flood of images” (German: Bilderflut), especially related to digital media. This makes it unavoidable for researchers to consider how this visuality shapes our world. From the 1990s onwards, several image focused turns were identified in and by art studies and other humanities, e.g. the “imagic turn” (Fellmann 1991), the “pictorial turn” (Mitchell 1992), the “iconic turn” (Boehm 1994), or the “visualistic turn” (Sachs-Hombach 1993). The idea was to create and communicate knowledge not only in textual form but by using images. In this line of thought, we introduce a method that deals with images, and works with them, but does not generate or create images itself.

Aby Warburg was a German art historian who, among other things, dealt with the lasting influence of, what he called, ancient pathos formulae in the Renaissance (Warburg [1932] 1998, cited in Targia 2021:3). He attempted to comprehensively work on these pathos formulae in his work “Bilderatlas Mnemosyne” (Warburg 2020). In simple terms, a pathos formula describes emotional movements, gestures and facial expressions that occur repeatedly in images – even across epochal boundaries (cf. Warburg 2020, cit. in Targia 2021:3). More specifically, the term “formula” describes frequently used expressions and a particular memorability of certain visual details, e.g. fluttering robes (Targia 2021:3). Perhaps the collection of pathos formulas can be compared to a vocabulary (Targia 2011:3). His intention was to unveil continuity and transformation of cultural or collective memory, e.g. in the form of gestures. This approach was later also applied to objects beyond the history of art. As some content and its visual form or representation is always inscribed in the collective memory of society, this method can be applied to other sujets than the discovery of forms of expression of Antiquity in the Renaissance.

These inscribed contents and forms of representation of collective memory become particularly apparent when images are placed in relation to one another, viewed together, and examined. The goal lies in the detection of a “something more”, something beyond the mere visuality itself. This “something more” refers to the underlying levels of consciousness, meaning, or patterns that are assumed to be at work in structuring the visuals a society (re)produces and consumes. The aim is to find meaning and relation out from the visual material what is not so obvious at first sight.

Warburg described himself (cf. Didi-Hubermann 2016:251f.) and is described (e.g. by Scherer 2020: 2 Min 7 Sec.) as a “seismograph of his time”. He drew lines of social development. This is because the society of his time was undergoing turmoil so he experienced great upheavals (e.g., the founding of the German Empire in 1871; crisis and recession at the end of 19th century, World War 1 1914 to 1918, the Weimar Republic 1918 to 1933, the Golden Twenties (1920s), the devastating recession starting from 1929, and the rise of antisemitism and right-wing radicalization; cf. Rösch 2010: 21f.). The tectonic shifts found in geological layers are considered analogous to those Warburg found in cultural memory; he found deposits that resurface again and again. Here, images are understood as a condensation of such processes. This is where the fault lines can be found.

Warburg used the pathos formula to describe how certain symbols of Antiquity can persist and be found in Renaissance images. In his work “Mnemosyne-Atlas” he developed these pathos formulas further by arranging pictures on large panels that he found belonged together next to each other. He placed pictures with similar symbols, motifs and themes together and arranged the pictures on the panel until he thought they were coherent. It can be assumed that this work is not meant to be complete, as Warburg repeatedly rearranged it until his death – and accordingly repeatedly he came to new conclusions. Using different kinds of images, he broke the boundaries of art (and sciences of art). He placed everyday images, such as advertisements from the 1920s next to antique artworks, stamps next to copper engravings and so on. This was possible as photography was emerging at the time and so he was able to use reproductions of historic paintings and constellate every image he wanted.

Warburg himself left little written record of this work, especially regarding the Mnemosyne Project, so we have to rely on his practical work – the picture atlas – and the work of his collaborators Saxel (e.g. ([1930] 1992) and Bing (e.g. [1965] 1992: 442ff), secondary literature, as well as lectures and modern livestream talks. The method behind Warburg’s picture atlas, in the same way as visual studies in general, became increasingly interesting for art studies and art history as well as humanities and social sciences (cf. e.g.: Targia 2021, Schung 2011, Hübscher 2022). It may be suitable as a phenomenological-hermeneutic and constructivist approach in all humanities and social sciences that want to work with images.

Paragraph

Warburg tended to work in a linear, chronological or time-based manner. He attempted to find what runs through time. He discovered motifs, symbols, gestures and their meanings which occur through time. Therefore, he needed a lot of very deep background knowledge for this iconographical resp. iconological approach.

There are several possibilities of working with the method presented here. First, you can – as Warburg did – work in a chronological manner and look for motifs and their meanings that arise when you look over the time. Therefore, you need much knowledge about your topic and the respective zeitgeist. And in addition, you need a lot of time. One can say: Warburg worked his whole life on it.

Second, you can see it a bit more pragmatically. This is not what Warburg intended, but our research interest can, however, also be somewhat simpler. We could simplify this method a little bit and scale it down to our needs. For example, we could also take a selective look at the underlying meanings, structures and relations that run through the pictures. The method could gain results even if you do not look within a historical approach. For your interest the themes do not necessarily have to be of interest in a longitudinal manner as Warburg did it. You can choose a special theme or question at a certain point in time or space. Perhaps there is something (a motif, symbol or sign) that appears again and again, even somewhere it was not suspected, or you find something surprising, perhaps not even with the intention of the image’s creator. Or you may notice something else, e.g. that certain themes are only depicted in a certain way. And keep in mind, you do not have to find a new pathos formula. You have to find your formula fitting your research question.

This method was not made with quantitative research interests in mind (e.g. focusing on the number of images with a certain symbol). Instead, one of the preconditions is that the research interest has to have a qualitative focus on societal/cultural/social aspects, e.g. underlying social aspects, norms of behavior, social criticism, collective memory, feelings, or a “Zeitgeist” etc. Warburg focused on feelings and psychological aspects but for your question you can shift and widen the question. Or maybe you dare to have no specific question and discover what you will eventually figure out.

Warburg’s picture atlas is an experimental set of instruments (Weigel 2021:18 Min. 23 Sec.), a temporary state, a work that is always unfinished, which looks at enigmatic ways of representing social/cultural objects and so seeks to gain more knowledge. In the style of Warburg’s picture atlas “Mnemosyne”, images on a topic are positioned on an atlas panel (German: “Atlaskarte”) and shifted around until they make sense to the person working on it and at best (this is the aim) produce a gain in knowledge.

In a nutshell, this method composes a series of images in a picture panel. Images are not grouped together based on aspects of beauty or color matching, etc., but regarding content-related aspects. The result is a constellation, no poster, no picture book, no collage. It is no artwork; it is a research method. This work (collecting, considering, sorting, arranging, rearranging), which can continue dynamically and endlessly, may lead to different insights than perhaps would have emerged from a simple synopsis or serial and sequential viewing.

A challenge lies, firstly, in the data corpus: There must be enough available images for your research subject and, secondly, you must have an appropriate amount of background knowledge of your topic. Thirdly, you should have a certain patience and sensitivity – a willingness to engage with the method and your sujet – and be willing to go through the questions you have for the image(s). If you do not engage with this method and try to use it as a recipe you could end up disappointed because this method is sensitive and cannot guarantee results or the specific results you have focused on. It could take a very long time, or it could take several starts. You could end up with no results or with a different question. But that’s the nature of scientific research.

Limitations

It is necessary to stress that Warburg worked iconographically/iconologically and had a wealth of background knowledge for interpreting the images and finding the pathos formulas. The interpretation is difficult and needs background knowledge because a motif can be interpreted in different ways, can be multi-layered or ambiguous. The motif can also be semantically reloaded again and again (Targia 2021: 4, 8). That means that one symbol can be used in different ways over time. Background knowledge corresponding to the research interest therefore must be available in order to carry out an in-depth analysis. However, it does not necessarily have to be the art-historical analysis of artwork that is of interest. Everyday phenomena may also be of interest for the method proposed here. What is important is the idea of hidden layers of meaning in pictures that can be found. This also works with modern pictures.

In addition, a certain “engagement” with this sensitive method and the respective images is necessary. The method is unsuitable if you are in a hurry or interested in quantitative research. The method is experimental; irritations or dead ends are to be expected (cf. Weigel 2021: 17 Min 54 Sec.).

It is also important to remember that you can only see “through your own eyes”. Images that are to be processed, even – or especially – if they are taken from other cultural/temporal contexts, can only be understood with the knowledge/experience of the analyzer in the present. Certain aspects, levels of meaning or symbols of some images may therefore remain closed. It is important to reflect on this limitation as much as possible.

Nevertheless, since researchers only ask questions to their atlas panels (German: Atlaskarte) from their own scientific background, their own perspective, they should still come up with results that are useful.

Finally, copyright and data protection regulations must also be considered when working with images. This applies less to private use, but especially if the results are to be published.

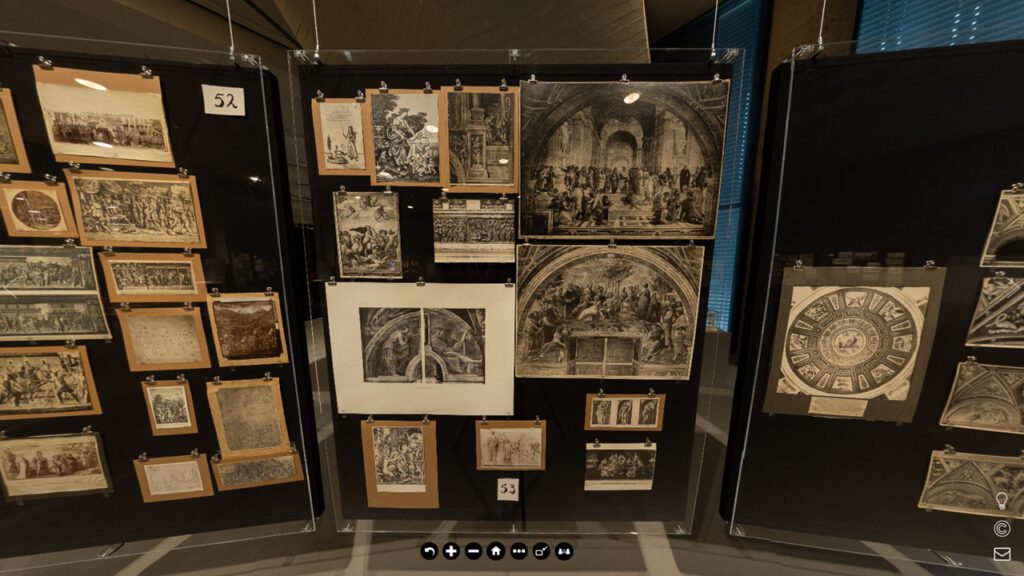

Figure 1: Screenshot of the virtual exhibition “Aby Warburg. Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. The Original.” at Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin. On display are 6 out of 63 panels from Aby Warburg’s picture atlas “Mnemosyne”. https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/virtual-tour-aby-warburg-bilderatlas-mnemosyne-exhibition-haus-der-kulturen-der-welt

Procedure

Even without a scientific background in art history, this method can be used to gain knowledge and experience. Warburg had an enormous amount of background knowledge about the pictures he worked with. Other researchers also have their own specific background knowledge that is useful for their research topic.

- Step 1: Search for a topic: Think about what you want to know or find out. E.g.: How a concrete catastrophe is visually processed or delt with? How is the phenomenon hurricane illustrated in images over time? How is fear represented in pictures? What about recurring pictures of politicans and their poses? How are politics choreographed? Which forms of expressions for rejection can be found. What can you tell from that? You can also take a more open approach to your research interest and just see what comes up. Perhaps you initially want to find out more about your topic or find connections. That can also be enough at first. So: discover your topic and write it down.

- Step 2: Decide on your source: analog or digital? Think about whether you want to work with analog or digital images. Both is possible. You can also combine the formats of the images, but you will have to convert one into the other. If you want to publish your work, pay attention to the image rights in advance.

- Step 3: Prepare the canvas: Open a blank document in an image editing or publishing software of your choice. It is important that you can load different images into one document, like on a collage or a poster. If you are working analog, you will need a canvas, a large sheet, a cardboard or paper: something on which you can arrange AND move – i.e. constellate – the images you have found.

- Step 4: Search for images: Start with the image search. Use common search engines or databases and various keywords that come to mind for the topic. You can also search step by step and start again once you have actually “ended” your work. Or enter a library and make copies. However, save your findings with adequate references. When you think you are finished and/or nothing new comes up, close your search (for the time being). Bear in mind that you may also find something in other subject areas that at first glance may have nothing to do with your question. If you have an intuition, simply add this “other” image for now. What about this symbol, gesture, thing: why is this always coming up in my pictures? What about those politicians?

- Step 5: Constellate: Start arranging the pictures. First of all, trust your intuition. There is no reading direction, no ordering rule, no hierarchy, unless you create one. Arrange the images next to each other, under each other, clustered or spread out – whatever you think is right or your topic needs. Try (intuitively/later also consciously) to create connections. And arrange the pictures together that you think belong together. It can happen, and is also wanted, that you arrange images that do not belong to the “actual” theme at first sight. Do this. There will be a connection that seems important to you and it may also tell something. Keep in mind: You are creating a constellation, no collage, no poster. It does not have to be beautiful. You are working on research contents not on beauty, advertising or artwork. If you are working analog: Don’t glue the pictures down! When you feel, you have finished arranging, stop. You can save the step by taking a photo.

Have you noticed any differences? Or Commonalities? What about these symbols, are they changing, always the same, do they reemerge? Which symbol for which feeling is used? Is there anything conspicuous about seeing something together? What about those politicians’ attire? Their gestures? The looks on their faces? - Step 6: Step back: Put the work aside and take a break. Come back to the work later. Are you finished? Is there anything else that needs to be added or rearranged? Did you find another thing reemerging again and again? Or other interesting aspects of this topic? Maybe symbols for dealing with feelings/problems? Does an object come up again and again? What about the stages politicians appear on? What do they look like when they appear bored?

- Step 7: Finish: You will have been thinking while you were working. You will without doubt have addressed further content-related problems when asking yourself what should be arranged, how and where. Why is this feeling represented with this certain symbol? How are these politicians staging? Maybe it is the genuine dimension of their performance that you are interested in? Record your thoughts and findings (preferably in writing). You will now have found out something about the topic. Perhaps something profound, perhaps something that is seemingly only incidentally interesting, perhaps social, historical, psychological backgrounds that were not directly obvious. Something that was there, in plain sight, but so far succeeded to be revealed. That is the main purpose of the method. Don’t be disconcerted if you don’t immediately come across major social upheavals or hidden psychological structures. Start slowly. Start small. Have you seen other catastrophes on pictures? Is there anything similar in their presentation? Have you noticed how politicians shake each other’s hands? Or how they observe each other? More and more will become apparent. The small aspects will turn to larger discoveries eventually.

Requirements

- Target group: anyone who would like to engage with image work, anyone who has some background knowledge of a topic, anyone who is willing to engage with a sensitive method

- Time frame: a few hours to several days. The work can be done again and again.

- Workspace: table/wall/floor (analog work) or desk workstation (digital work)

- Work requirements: canvas/cardboard/paper and access to libraries/collections/archives (analog) or a PC and an Internet connection as well as possibly access to a search engine/digital archives/databases (digital)

- Skills: Knowledge of researching databases/archives/collections and reproduction options for images (analog) or basic knowledge of PC work (using browsers, digital archives, saving data, basic image processing) (digital)

- Technical necessity: PC and Internet access (digital)

- Supervision: not obligatory, but recommended for first-time participants or young researchers

- Costs: no further costs apart from Internet access and possibly contributions to libraries/archives/databases

- Description of the necessary software functions: If you work digitally, you will need an Internet connection and a browser for research. After that, all common image editing, publishing, typesetting or design software is to be used. Presentation software or even word processing programs with an image function are also suitable. You can also use simple paint programs. The software only needs to be able to insert images from your computer and arrange several on one sheet/file.

Rating

- Contexts: The method in Warburg’s picture atlas was used by him to find pathos formulas. This can be – for this method represented here – simplified for some purposes: Perhaps other formulas or recurring patterns can be found in pictures. Whenever it might be interesting to approach a topic visually instead of (or in addition to) textually and when more information is to be expected, this method can be tried out. It seems particularly promising when emotional and cultural components are present or suspected in the topic. Particularly suitable for open-minded researchers who are keen to experiment.

- Cost: Overall, it is a time-consuming but not financially costly method. Costs are only incurred if there is no common software or Internet connection (digital) or expenses are incurred for paper sheets and printouts/reproductions of the images (analog). A few Gigabytes of storage space must be available on the PC. Preparation and organization are convenient, moderation can be omitted. A group or supervisor may be useful for reflection.

Example

As part of a training course on “Working with digital images in geography lessons”, the participants were asked to create a panel on the subject of “Hurricane Katrina”. The question was how Hurricane Katrina was dealt with in everyday life. The panel presented here as an example shows images that can be assigned to art. There were also more documentary-style panels with press or private photos, for example. It represents a very simple way of working with this method and the question was not in a chronological manner. But it shows the idea.

Two of the seven selected images show situations in water. The others show fire, grotesque, burning landscapes or wind with fire. One picture shows smoke from the fire forming a skull. The pictures have a very frightening effect. It is interesting to note that many of the artworks/paintings created in this context tend to depict fire.

The damage caused by Hurricane Katrina was mainly water damage from the subsequent storm surge, rather than damage caused by the wind itself or fire. Fire as an artistic symbol is multifaceted and has changed throughout history. At this point, it can be read as a symbol for an inferno, great misfortune, great damage, catastrophe, injury, pain, accident, drama…. This is certainly how the catastrophe was perceived. The works of art therefore reflect the feeling of/through the catastrophe rather than how the masses of water were dealt with. In this way, this catastrophe is obviously inscribed in (cultural) memory as a painful, burning experience.

Figure 2: panel created on the subject of (everyday life and artistic) processing the social catastrophe Hurricane Katrina. The pictures you see in this panel are recreated by an AI-tool (DALL·E) to save the copy rights of the original pictures. The topics they communicate are the same and the way they look is similar. The figure is for illustrative purposes only. You can see the original references in the bibliography. (Many thanks to Frank Meyer for helping with AI simulation of the panel)

Funding: This text was written as part of the BMBF-funded ReTransfer project, which is financed by the EU.

References

Bing, G. ([1965] 1992): A.M. Warburg. In: Wuttke, D. (Ed.): Aby M. Warburg. Ausgewählte Schriften und Würdigungen. Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner. 437-454.

Boehm. G. (1994): Die Wiederkehr der Bilder. In: Boehm, G. (Ed.): Was ist ein Bild? München: Wilhelm Fink. 11-38.

Fellmann F. (1991): Symbolischer Pragmatismus. Hermeneutik nach Dilthey. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Hübscher, S. (2022): Visuelle Rhetoriken: Bild Re-/Produktionen und mediale Wissenstransfers. In: Zulaica y Mugica, M. & K-C. Zehbe (Eds.): Rhetoriken des Digitalen. Adressierungen an die Pädagogik. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-29045-0_6. 105-124

Mitchell, W.J.T. (1992): The Pictorial Turn. In: Artforum. Reinbek: Rowohlt.

Rösch, P. (2010): Aby Warburg. Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink.

Sachs-Hombach, K. (1993): Das Bild als kommunikatives Medium. Elemente einer allgemeinen Bildwissenschaft. Köln: Herbert von Halem.

Saxel, F. ([1930] 1992): Warburgs Mnemosyne-Atlas. In: Wuttke, D. (Ed.): Aby M. Warburg. Ausgewählte Schriften und Würdigungen. Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner. 313-315.

Saxl, F. ([1932] 1992): Die Ausdrucksgebärden der bildenden Kunst. In: Wuttke, D. (Ed.): Aby M. Warburg. Ausgewählte Schriften und Würdigungen. Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner. 419-431.

Scherer, B. (2020): Interview zur Ausstellung: Aby Warburg. Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. The Original. Haus der Kulturen der Welt und The Warburg Institute. https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/virtual-tour-aby-warburg-bilderatlas-mnemosyne-exhibition-haus-der-kulturen-der-welt [access: 05.11.2024]

Targia, G. (2021): Pathosformel In: Berek, M., K. Chmelar, O. Dimbath, H. Haag, M. Heinlein, N. Leonhard, V. Rauer & G. Sebald (Hrsg.): Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Gedächtnisforschung. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien. 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-26593-9_140-1

Warburg, A, ([1906] 1992): Dürer und die italienische Antike. In: Wuttke, D. (Ed.): Aby M. Warburg. Ausgewählte Schriften und Würdigungen. Baden-Baden: Valentin Koerner.

Warburg, A. (2020): Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. The Original. Ed. Roberto Ohrt, R. & A. Heil in cooperation with The Warburg Institute and Haus der Kulturen der Welt. Berlin: Hatje Cantz.

Weigel, S. (2021): Wohin führt der Atlas? – Aby Warburgs Erbe und die Zukunft der Ikonologie. Livestream-Talk, Bundeskunsthalle https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p02DLmpfxvw [access: 01.11.2024]

Reference Exhibition:

„Aby Warburg Bilderatlas Mnemosyne. Das Original.“ at Haus der Kulturen der Welt Berlin. Website from Warburg Institute London: https://warburg.sas.ac.uk/virtual-tour-aby-warburg-bilderatlas-mnemosyne-exhibition-haus-der-kulturen-der-welt [access: 19.07.2024]

Image generating AI used:

Dall·E from Open AI

Image Sources of original images:

Anonymous (2015): Hurricane Katrina Painting Original 16 x 20 Acrylic Art New Orleans Saints Flood | #1915066802 (worthpoint.com) https://www.worthpoint.com/worthopedia/hurricane-katrina-painting-original-1915066802

Garnet, J. (2005): Flood (2) (Strange Weather series). https://openverse.org/image/95897a53-ff69-4a66-9a46-759f53bff30c?q=strange+weather CC BY-SA 2.0

Garnet, J. (2005): Evac (Strange Weather series). https://openverse.org/image/fa56cbf7-547c-48ca-bd0b-f102d9e63b9e CC BY-SA 2.0

Garnet, J. (2005): Flood (Strange Weather series). https://openverse.org/image/2413f80a-c76c-4bfb-9ba0-6788d9f7e33f CC BY-SA 2.0

Garnet, J. (2005): Strange Weather (2) https://openverse.org/image/288a5864-eddf-4d4b-9b65-6a2e959ae3d0 CC BY-SA 2.0

Garnet, J. (2005): Plum 2 (Strange Weather series). https://openverse.org/image/5f24e942-9dfc-405f-99d0-81cf256daf96?q=hurricane%20katrina%20art CC BY-SA 2.0

El Franco Lee (2005): James Byrd 1. https://thedailycougar.com/2012/03/18/grad-student-reaches-youth-with-art/

Leave a Reply