Making a Comic Book with Peer Workers in British Columbia, Canada

Author:

Sophie McKenzie

Citation:

McKenzie, S. (2024): Pen Mendonça’s ‘Values-Based Cartooning’: Making a Comic Book with Peer Workers in British Columbia, Canada. In: VisQual Methodbox, https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2024/05/31/pen-mendoncas-values-based-cartooning/

Essentials

- “Values-based cartooning” is a research method for exploring complex ideas involving a deep reflection upon emotion and engagement with lived experience of the topic at hand whilst illustrating emotionally-difficult circumstances and topics (Mendonça, 2016, 2018).

- Pen Mendonça’s values-based cartooning involves reflection on emotions and engagement with lived experiences.

- This method of illustrating encourages the creator to follow their affective and emotional instincts, allowing for the inclusion of diverse works.

- It is a “social practice” underpinned by six principles: openness and clarity of purpose, self-awareness, listening, observing, emotional engagement, contextual knowledge, representing diverse experiences, and critical thinking (Mendonça, 2021, p. 6).

- The process entails engaging with multiple perspectives, checking back with collaborators, explicitly inviting critique, negotiating conflicting agendas, and engaging with powerful emotions (Mendonça, 2021, p. 5).

Description

Values-based cartooning involves recognition of “the role of personal, professional, participant and organizational values, and an ability to negotiate these when developing graphics, single-panel cartoons and comic strips” (Mendonça, 2018, p. 24). In other words, it involves reflecting upon the moral and ethical standpoints of all participating parties. It is underpinned by six principles: openness and clarity of purpose, self-awareness, listening, observing, emotional engagement, contextual knowledge, representing diverse experiences, and critical thinking (2021, p. 6). This process entails engaging with multiple perspectives, checking back with collaborators, explicitly inviting critique, negotiating conflicting agendas, and engaging with powerful emotions (Mendonça, 2021, p. 5). It requires both advanced digital illustration and facilitation skills, and is therefore limited to practitioners with artistic affinities and strong interpersonal skills (Mendonça, 2018, p. 35). The “social practice” of values-based cartooning proved to be a potent tool in elucidating reflection and generating an artistic product which has a social life in our communities (Mendonça, 2018).

The development of comic strips is a prominent avenue through which values-based cartooning has been applied to illustrate and represent challenging life experiences. Graphic novels, a series of comic strips of a similar topic which have been compiled into a book format, have been widely used as a medium through which both artists and interlocutors engage with emotionally difficult topics such as death, grief, and illness (Forney, 2012; Small, 2009; Streeten, 2011). Ethnographic research presented in a graphic format has a more recent history, with a cascade of works within the last five years (Bucken-Knapp & Sildre, 2022; Carrier-Moisan & Santos, 2020; Hamdy et al., 2017, 2017; Jain, 2019; Schuster et al., 2023; Sopranzetti et al., 2021; Waterson & Corden, 2020). These works demonstrate “engagement with affective details that would otherwise go unnoticed” (Rumsby, 2022). In the words of graphic ethnographer Dimitrios Theodossopoulos, the graphic novel form welcomes engagement with unexpected views, affective subtleties, and feelings which “are frequently lost or hidden behind words” (Theodossopoulos, 2022a). Similarly, graphic novels which are based on ethnographic research are a testament to how “what is said or argued cannot be distinguished from how it is presented and communicated” (Jain, 2022).

Procedure

For my masters of anthropology (MA) program at the University of British Columbia (UBC), I carried out a participatory arts-based project in which I collaborated with three peer workers to produce a comic book about their experiences working throughout the overdose crisis in Canada. Peers are people with lived/living experience with substance use who use that lived experience in their professional work such as in harm reduction programs. There have been few avenues through which peer workers have been explicitly recognized and validated for the life-saving work they do. Our graphic novel project entitled Peer Life: A Degree in Street Knowledge was an avenue through which peers could process their experiences and see their stories reflected in a visual format.

In this project, I acted as an ethnographer-artist and could deepen my epistemological engagement and harness immediacy as a critical tool in translating participants’ narratives (González, 2022). My ability to draw either during meetings with participants or soon after is invaluable in both capturing immediate affective dynamics and eliciting instant commentary from peers which helps generate more nuanced storylines.

Here are some guidelines for carrying out your own collaborative project whilst adhering to Mendonça’s “values-based cartooning”:

- Step 1: Engage with your collaborators to identify the stories/narratives that they would like to be highlighted in your visual product. This step may take the longest, as motivations, intended audiences, and ethics of representation should be explored in detail prior to beginning artistic work.

- Step 2: The artist will preferably lightly sketch the first draft in the presence of their storytelling collaborator so that things can be immediately erased and re-drawn. If this is not logistically possible, then the artist can attempt a first pencil draft on their own whilst carefully considering their collaborator’s ideas. The artist should highlight details that can be changed such as: facial expression, furniture featured in a room, bodies of characters, clothing, colours… etc. Whilst illustrating, the artist should carefully consider the affective impact of their visual choices and reflect upon the power dynamic between themselves and their collaborator. By this, I mean that consideration of the ways in which their illustrations will move people or trigger certain responses is integral. Part of this process is also identifying the text that will be featured in each narrative box and speech/thought bubble.

- Step 3: Once the pencil sketch has been enthusiastically approved by both the artist and storyteller, then the artist can proceed with colouring. The illustrator should consider the affective nature of colour theory and how certain palettes can be associated with specific moods or impacts.

- Step 4: Once the comic strip is “complete”, the artist should emphasise to their collaborator(s) that anything can still be changed. Attention should be paid to ensure that storytellers do not feel pressure to settle upon a strip because they don’t want to create more work.

Requirements

Researchers who use this method should be (1) well-versed in the specific socio-political context of the people with whom they are working to foster a broader knowledge base from which they can draw when illustrating, (2) experts in their chosen mode of illustration to ensure ease and efficiency of collaboration, and (3) familiar with trauma-informed and anti-oppressive practices as they are grappling with the responsibility of ethically representing human suffering. It is therefore only an individual with a diversified skill set that can successfully carry out this work.

Evaluation

It took me about 6 months to produce this comic book whilst working on it most days of the week. I would not have laboured at this intensity if it weren’t for the tight timeline of my masters program. I worked iteratively rather than algorithmically, which made it so that I could not predict how much illustration work would be required in a given week. I submitted myself to the desires of my peer collaborators so as to be available to capture their ideas and most authentically represent their narratives. Whilst I received a small grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) which enabled me to pay my collaborators an hourly wage for their time as reflected in the BC Centre for Disease Control Peer Payment Standards and print a few comic books upon completion, much of this work came out of my own pocket. Therefore, the time of collaboration and of actually visualising, as well as the related costs should not be underestimated.

My dual role of ethnographer, illustrator, editor, and acquaintance of my collaborators brought about several challenges. First, and most prominently, the process of illustrating was significantly more laborious and time-consuming than I expected. My initial goal was to produce a new comic strip weekly, but I quickly fell behind on this endeavour. I struggled to maintain a balance between producing quality illustrations which appropriately reflect my colleagues’ narratives and moving the project along, given the tight 2-year timeline of an MA degree. Second, meeting with my collaborators required me to spend multiple hours on public transit as I don’t own a vehicle. I tired easily during this work due to long hours on buses and trains, continuous engagement with painful topics, and the daily manual labour of hunching over my iPad. Third, I did not yet have specialised expertise in comic illustration and formatting prior to beginning the project. I learned specific techniques using various online resources as I went along which took many hours.

Example

The Peer Comic Book Project involved the collaboration of a researcher (Sophie) and three peer workers living in British Columbia, Canada. This work was completed as a part of Sophie’s Masters of Anthropology program at the University of British Columbia. The goal of this comic book is summarised by the storytellers: “We hope that this comic book will make peers feel seen and change other people’s minds about people who use drugs” (Howell, Amy et al., 2023).

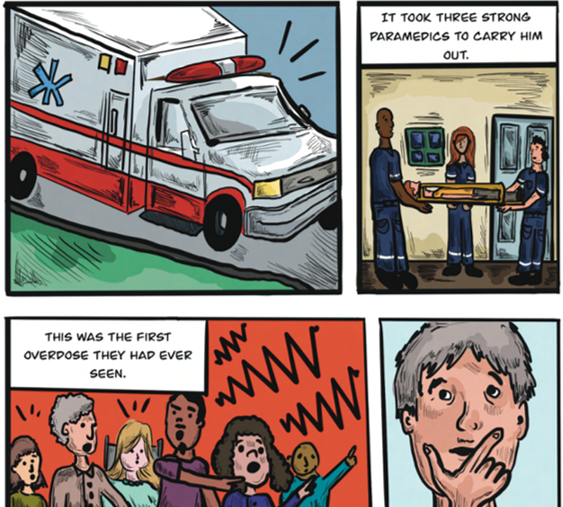

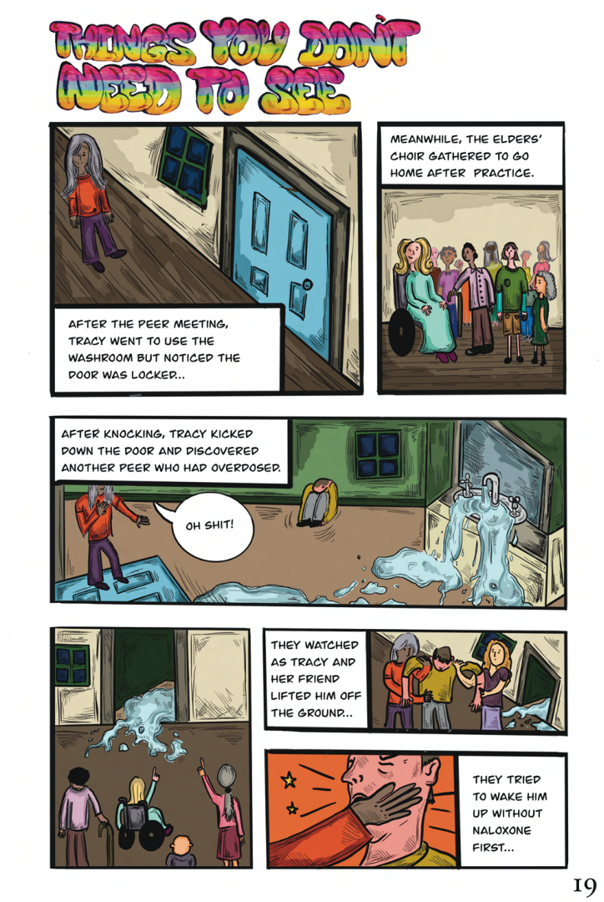

The comic strip you see below was developed with one of my peer collaborators who chose to highlight a true story that happened after one of her peer team meetings. We met once per week or biweekly, depending on how much illustration work I was able to complete. In alignment with values-based cartooning, my collaborator and I carefully considered the following:

- Openness and clarity of purpose: Whilst both settling upon the storyline and developing imagery, I frequently reminded my collaborator about the intended outcome of this work – a by-product of my master’s thesis and an unrelated knowledge translation product that would be distributed to wider audiences. Relatedly, we had to consider specific ways in which to anonymize the story. This process also required reflection upon how the comic strip would conclude; we engaged in a lengthy dialogue on whether it should end hopefully or realistically. My colleague decided that a hopeful ending would best fulfil the graphic novel’s intended purpose of eliciting sentiments of inspiration and respect toward peer workers.

- Self-awareness: I frequently checked in with my own biases throughout the comic book development process. I became attuned to my tendencies to subconsciously align with stigmatising rhetoric towards people who use drugs, and intently worked to counter this habit.

- Listening and observing: In addition to listening carefully to my collaborator’s stories, I also observed the way they told them. Their body language, tone, facial expression, and level of detail were all important clues which indicate the meaning of the story to them. I ensured that I was fully present prior to our collaborative sessions, and rescheduled if I did not feel I could fully commit to the tenets of values-based cartooning.

- Emotional engagement: I regularly and vehemently acknowledged throughout the project that these are difficult stories that have the potential to impact me personally. I laboured to not fall into the classic ‘objective researcher’ trap which often involves emotional distance and stoicism. It is my emotional engagement and dedication to my collaborators’ stories that contributed to the quality of the comic strips.

- Contextual knowledge: I have worked in the field of drug policy and harm reduction for five years and have extensive knowledge on peer workers as well as the overdose crisis. This in-depth contextual knowledge equipped me with a baseline understanding of some aspects of my collaborators’ realities, enabling us to work more expediently. I was eager to ensure that they did not have to over-explain themselves throughout the process.

- Representing diverse experiences and critical thinking: Throughout the process, we were careful to include diverse and sometimes conflicting experiences/stories. Inherent in values-based cartooning is the recognition that oftentimes only one set of values/morals/ethical standpoints is visually represented in artistic works, and this methodology works to combat and complicate this tendency.

One of the comic strips in Peer Life: A Degree in Street Knowledge entitled “Things You Don’t Need to See”

Useful Resources

Suggested Tools

- Procreate: https://procreate.com/

- iPad https://www.apple.com/ca/ipad/ and Apple Pencil https://www.apple.com/ca/apple-pencil/

References

Aalders, J. T., Moraa, A., Oluoch-Olunya, N. A., and Muli, D. (2020): Drawing together: making marginal futures visible through collaborative comic creation (CCC), Geogr. Helv., 75, 415–430, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-75-415-2020.

Bucken-Knapp, G., & Sildre, J. (2022). Messages from Ukraine. University of Toronto Press.

Carrier-Moisan, M.-E., & Santos, D. (2020). Gringo Love: Stories of Sex Tourism in Brazil (W. Flynn, Trans.). University of Toronto Press.

Forney, E. (2012). Marbles: Mania, depression, michelangelo, & me, a graphic memoir. Avery.

González, J. S. (2022, July 8). Otherwise Comics. Society for Cultural Anthropology. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/otherwise-comics

Hamdy, S., & Nye, C. (2022, July 8). Lissa’s Multimodal Ethnography and Revolutionary Citation. Society for Cultural Anthropology. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/lissas-multimodal-ethnography-and-revolutionary-citation

Hamdy, S., Nye, C., Bao, S., Brewer, C., & Parenteau, M. (2017). Lissa: A Story about Medical Promise, Friendship and Revolution. University of Toronto Press.

Howell, Amy, Scott, Tracy, Seguin, Ryan, & McKenzie, Sophie. (2023). Peer Life: A Degree in Street Knowledge

Jain, L. (2019). Things that Art: A Graphic Menagerie of Enchanting Curiosity. University of Toronto Press.

Jain, L. (2022, July 28). Companion Images. Society for Cultural Anthropology. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/companion-images

Mendonça, P. (2016). Graphic facilitation, sketchnoting, journalism and ‘The Doodle Revolution’: New dimensions in comics scholarship. Studies in Comics, 7(1), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1386/stic.7.1.127_1

Mendonça, P. (2018). Situating Single Mothers through Values-Based Cartooning. Women: A Cultural Review, 29(1), 19–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/09574042.2018.1425534

Schuster, C. E., Bernardou, E., & Bueno, D. (2023). Forecasts: A Story of Weather and Finance at the Edge of Disaster. University of Toronto Press.

Small, D. (2009). Stitches: A Memoir. Mclelland & Stewart.

Sopranzetti, C., Fabbri, S., & Natalucci, C. (2021). The King of Bangkok. University of Toronto Press.

Streeten, N. (2011). Billy, Me & You. Myriad Editions.

Waterson, A., & Corden, C. (2020). Light in Dark Times: The Human Search for Meaning. University of Toronto Press.