Author:

Nicola Richter

Citation:

Richter, N. (2024): Exploring Internal Images through Perceptual Exercises. In: VisQual Methodbox, https://visqual.leibniz-ifl-projekte.de/methodbox/2024/05/31/exploring-internal-images-through-perceptional-exercises/

Essentials

- Internal images, which “represent something that is not present in itself [through senses other than sight, note NR]” (Wulf 2014, 9), determine our perception of the world. The internal images (e.g. memory images, image drafts) differ from those that are perceived in that they are blurred (ibid.). They conjured by a researching activity are transformed into the imaginary through bodily and possibly affective engagement with said activity (Wulf 2014, 50). The generation of these internal images is subjectively anchored, and we are affected by them. We experience ourselves within them and can assure ourselves of ourselves with their help (Wulf 2014, 114).

- Perceptual exercises are tools used to create fields of experience and research, allowing for the conjuration of internal images. The focus of such an exercise is not the outcome-based product, but the process of engaging with and through the unfamiliar. The exercises are effective in uprooting the automated, “perception-trained” gaze inherent in research by addressing and confronting the unfamiliar (Wardenga 2006, 41).

- Phenomenological attitude: The order that structures our perceptions and interpretation possibilities can be elusive due to the unfamiliarity (cf. Waldenfels 1997). By enhancing the perception of phenomena (from the Greek ‘phainómenon’, meaning ‘the appearing’) through exercises, experiencing the unfamiliar can be understood as a positively connoted condition within a subject in which a critical approach to research through „the questioning of self-evidences or expectations of normality“ (Koller 2016: 215) can be achieved.

Description

Individuals and collective communities interpret the world through the medium of images. These images are imagined, remembered, combined, and so forth, with the help of imagination, thus creating reality (Wulf 2014, 12). At the same time, imagination also creates new images through reality, through which we interpret the world (ibid.). Symbolic orders link imagination and reality, as demonstrated by the concept of ‘geographical imaginations’ (Gregory 1994; Jahnke 2012; Gieseking 2017). The capacity to imagine allows individuals to construct a mental representation of the world, which in turn influences their perception of reality.

The concept of the imaginary can be understood in two ways. Firstly, it can be regarded as a materialised world of images, sounds, touch, smell, and taste (Wulf 2014, 12). Secondly, it can be considered to be the human capacity to create such a world.

This process can be utilized in research: The own confrontation with objects of research in the research process that are considered ‘alien’ creates the possibility of encountering oneself and others with openness. Therefore, transformative research, using the phenomenological concept of the unfamiliar, can be seen as a challenge to an individual’s world and self-relations through the experience of crisis or failure which can be introduced as an impulse. Furthermore, it can be seen as productive, opening up new emotions and associations and thus potentially explicating implicit assumptions and premises. The moment of crisis, as it were, reveals that previously acquired orientations, existing perceptual, interpretive, and action-related dispositions may not be adequate to respond to a new problem. To discover new possibilities for experience and cultivate perception of the transformation of self and world relations, it is thus necessary to break out of routine actions and endure the ambiguous and complex internal images that accompany it.

On the one head, researchers may utilize this mechanism to trigger subjects into becoming aware of their internal images. On the other hand, this cultivation of internal perceptual capacity can be achieved through perceptual exercises that focus on the perceiver and their individual experience of the world and their self, thus allowing for training self-reflection. These exercises utilize the unfamiliarity of otherwise familiar material to provide unexpected access to the subject matters, room, and oneself.

During the initial encounter with the task at hand, researchers may experience uncertainty due to the openness of the concept in the research process. It can be difficult for the researcher to get used to the unfamiliar setting. It is important to acknowledge and work through these moments of hesitation as they can be productive for the research process. Perceptual exercises can stimulate curiosity and activate thinking processes, leading to the formation of internal images. Ideally, researchers are encouraged to explore new and unfamiliar experiences beyond their geographical perspective.

Procedure/Example: House – Dog – Tree (modified from Antons 1992, p. 115)

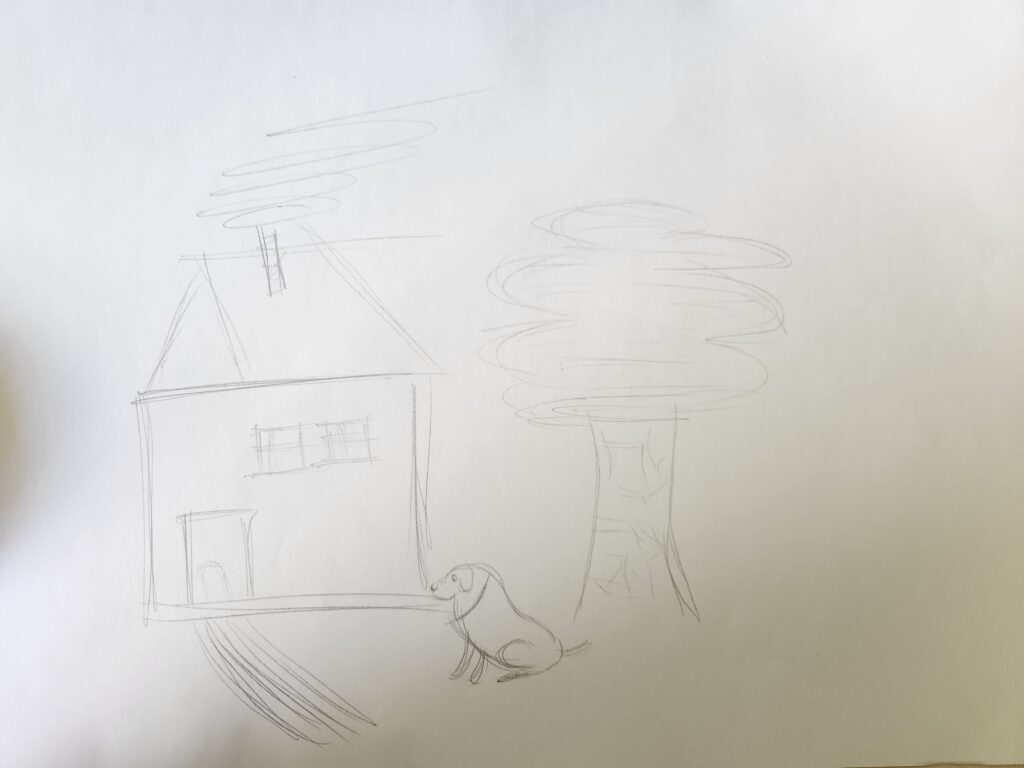

In the following, an example perceptual exercise called “House – Tree – Dog” is introduced, along with prompts for reflecting on the insights gained, which are crucial for the research process.

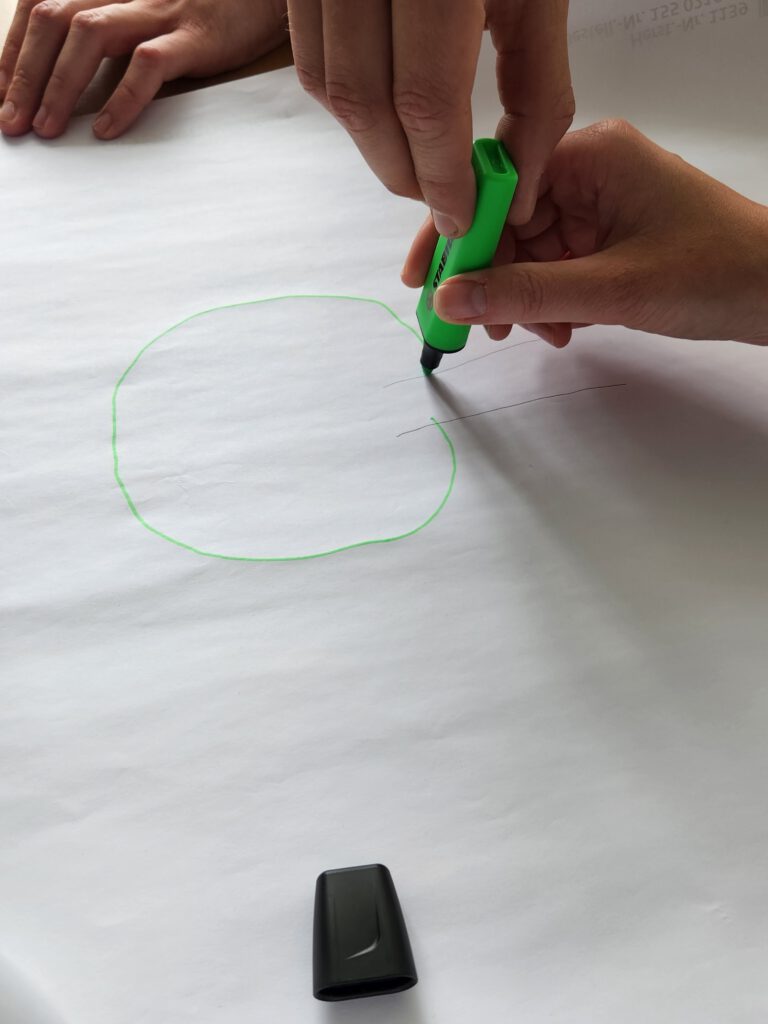

- The exercise involves two participants sitting at a table with pens and a single sheet of A4 paper in front of them.

- The two participants choose one pen between them without communicating to each other and draw a house, a tree, and a dog together.

- They label the drawings without communicating to each other.

- Then, without communicating with each other, they collaboratively assign a grade to their drawings and record it on the back of the paper.

- The drawings are placed on the floor of the room.

- Following a group discussion, the best drawing is selected, and the decision is explained.

Researchers approach the task non-verbally, challenging them to visualize their internal images in an individual manner while collectively engaging in a type of “searching movement”. Through the joint negotiation process of signing and grading, they sense the possible interplay of bodily movement with the material. This calm or dynamic searching movement creates new avenues through flexible exploration. Researchers become aware of themselves by perceiving and comparing the unique aspects of each drawing on the floor of the room.

After following the last instruction, a reflection round takes place where researchers exchange thoughts on their approach, impressions, and bodily sensations. For example, discussions may focus on how openly or skeptically participants approached the subject matters. Other discussion points could include: What similarities and differences exist between the drawings? How does my body interact with my partner and the material? To what extent do our “searching movements” align or not? Does the intensity of joint action change over time? Who determines the leading force of movement? What opportunities does this open up? Where were there non-verbal discrepancies or internal “struggles”? To what extent did my internal images influence the external representation? What does this exercise mean for my approach to space and to myself?

Reflecting on perceptual exercises within the research process brings negotiation and appropriation processes into focus. It involves taking a perspective shift and finding possible answers to contradictions/new thoughts/questions. Through deliberate promotion of perception, the significance of non-verbal aspects and internal images in the process becomes evident. These images make something visible that would remain invisible without them. This aspect is important for the research process on the part of the researcher, as it allows them to gain insight into the influence of inner images on orientation in the world and perception. By understanding the role of inner images in this process, researchers can also question their own research methodology in this respect. Self-reflection reveals the points of encounter in the research process: subject and object, world and person, person and person. These encounters modify, often unconsciously, the inner images that structure and organise our ideas of the world (Jahnke 2012, 28). These images that emerge from the imaginary can then also be transferred to new research contexts. The process of dealing with the internal images inherent offers new perspectives for dealing with the inherent openness and uncertainty of the research process itself. This allows for the uprooting of the automated, perception-trained view inherent in research (Wardenga 2006, 41).

References

Antons, K. (1992): Praxis der Gruppendynamik: Übungen und Techniken, Göttingen [u.a.]: Verl. für Psychologie Hogrefe.

Gieseking, J. J. (2017): Geographical Imagination. In: Richardson, D., N. Castree, M. Goodchild, A. Jaffrey, W. Liu, A. Kobayashi & R. Marston (Hrsg.): International Encyclopedia of Geography. New York: Wiley-Blackwell and the Association of American Geographers. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg1171

Gregory, D. (1994): Geographical Imaginations. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Jahnke, H. (2012): Geographische Bildkompetenz? Über den Umgang mit Bildern im Geographieunterricht. In: Geographie und Schule, 34, 195, S. 27-34.

Koller, H.-C. (2016): Über die Notwendigkeit von Irritationen für den Bildungsprozess. Grundzüge einer transformatorischen Bildungstheorie. In: Lischewski, A. (Hrsg.): Negativität als Bildungsimpuls? Über die pädagogische Bedeutung von Krisen, Konflikten und Katastrophen. Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh, S. 215-235.

Waldenfels, B. (1997): Topographie des Fremden. Studien zur Phänomenologie des Fremden I, Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Wardenga, U. (2006): Raum- und Kulturbegriffe in der Geographie. In: Dickel, M. & D. Kanwischer (Hrsg.): TatOrte. Neue Raumkonzepte didaktisch inszeniert. Berlin: Lit Verlag, S. 21-47.

Wulf, C. (2014): Bilder des Menschen: Imaginäre und performative Grundlagen der Kultur. Bielefeld: transcript.